Roger Gwynn: The British photographer who fell in love with Bangladesh

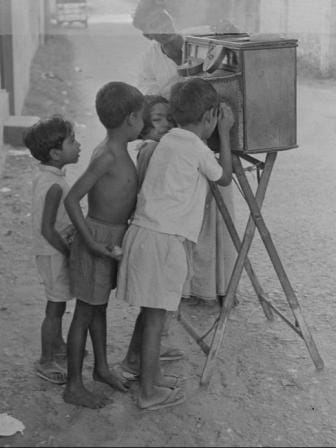

An old, wrecked car with children sitting on top, an old minivan crammed with ecstatic passengers, and children engrossed in watching movies in bioscopes. The rustic beauty of Bangladesh was captured in frames by British photographer Roger Gwynn, who arrived to Bangladesh as a volunteer, but fell in love with the country's simple and stunning landscape. He was so taken with Bangladesh, that he can still speak and write in Bangla flawlessly.

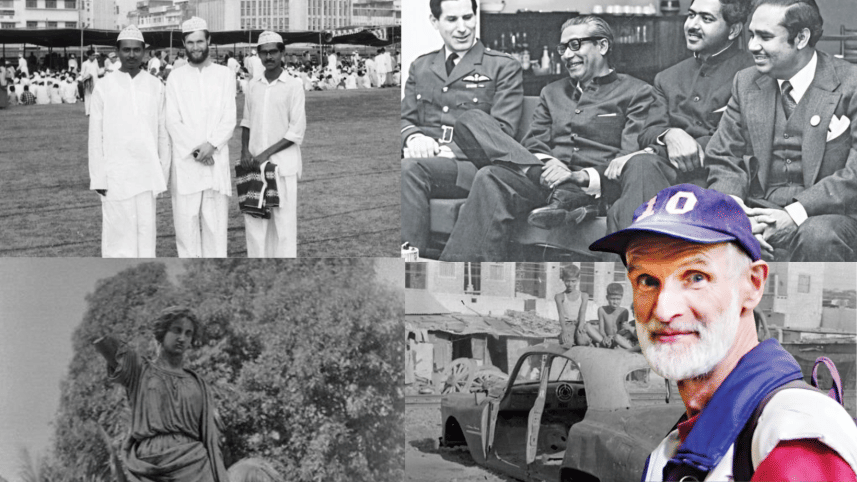

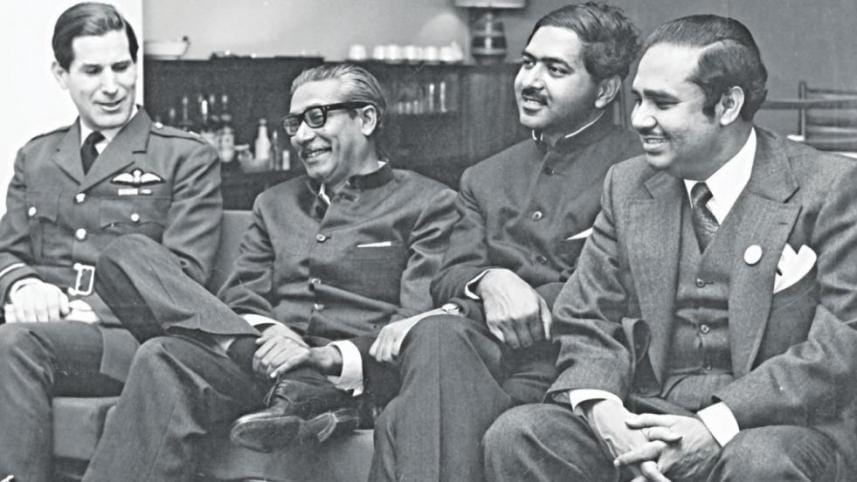

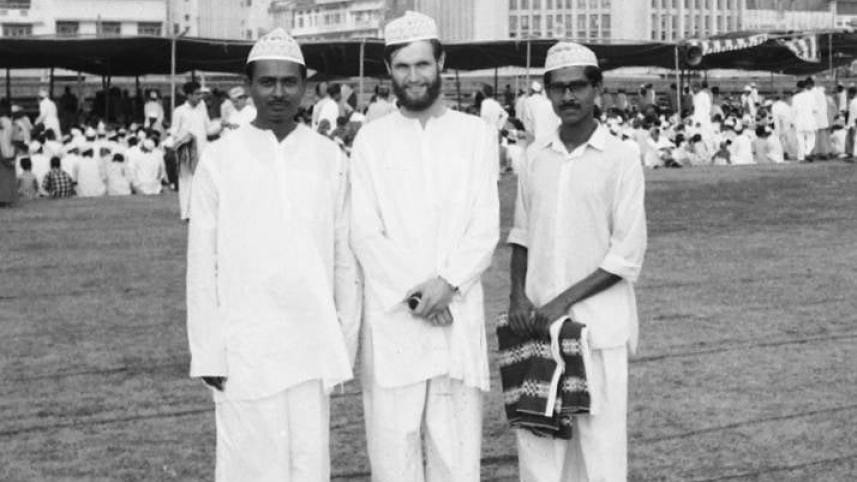

Roger Gwynn immortalised some of the most awe-inspiring images of the Birmingham protest against Pakistani brutality and genocide in Bangladesh in 1971. Additionally, he had the opportunity to meet the Father of the Nation, Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman, in 1972 at the Claridges Hotel in London. He again came back to Bangladesh after the Independence to help reform the country after the disastrous Cyclone in 1974.

In an interview with the Daily Star, the British photographer shared insights into his deep affection for Bangladesh and reflected on how his images continue to resonate in people's hearts, standing the test of time.

Edward Roger Gwynn, affectionately known among his Bangladeshi friends as Roger master, holds a special place as a close family friend of ours. My father narrated numerous stories about Roger, recounting his adventurous tales in our country. In the past, he used to send letters to my uncle in Bangla, inquiring about his whereabouts. As I went through these letters, I was genuinely struck by Roger's unwavering love for Bangladesh.

Feeling inspired by his enduring affection, I reached out to him via email and have a conversation with the man who fell in love with our country. In my emails, I addressed him as Roger uncle, and much to my delight, he responded affectionately, referring to me as his dear Bhatiji.

Born in 1941 in London, Roger Gwynn saw the brutality of war-torn countries, the pouring of bombs, the scarcity of food and the insurgent of refugees from the Nazi regime pouring in Britain.

After finishing his college, he earned a degree from Cambridge University in Social Anthropology.

Although he was a good student, Roger was quite confused about his aim in life, but he knew one thing for sure -- he wanted to travel and explore the world. At that time, the only two reasonable ways to travel was to either hitchhike or join a work camp. Through hitchhiking, he could move around, but with work camp, he had to stay in a place and meet people of various cultures.

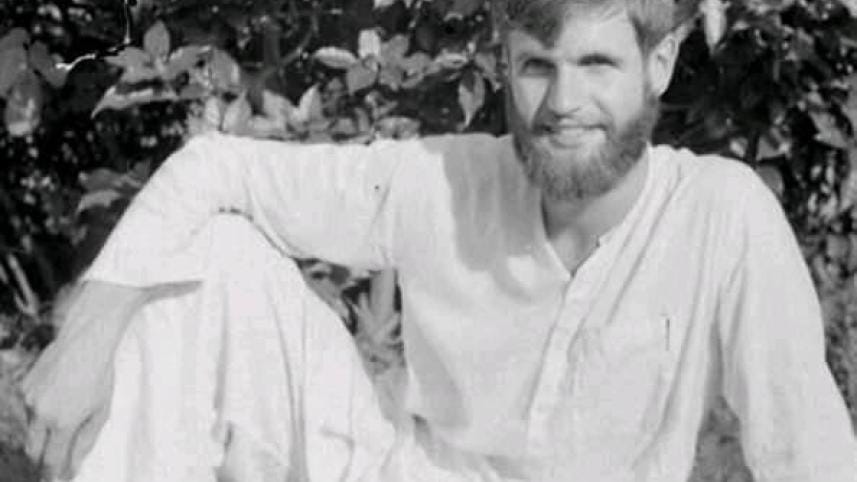

Soon, the British photographer become part of long-term voluntary work and he was sent to East Pakistan to help out the people.

"From November 1964 to December 1965, I worked under Service Civil International and I was stationed in different locations of Dhaka, Chittagong, Rajshahi and Barisal districts. During my brief period in Bangladesh, I became friends with some of my Bangladeshi colleague and I got to adapt the Bangla language. After that I came to Bangladesh a few more times as I considered Bangladesh as my second motherland."

Roger Gwynn was not a professional photographer, neither did he studied the art of photography.

"During my initial visit to Bangladesh in 1964-1965, I found myself captivated by the surroundings, prompting me to start capturing moments through photography. This newfound passion led me to document the authentic essence of Bangladesh—its beautiful landscapes and the unfiltered beauty of its people—through the lens of my camera."

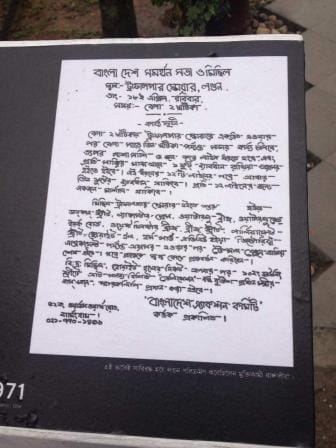

In 1971, Roger Gwynn, then working as a teacher in Birmingham, learned about the atrocities committed by the Pakistani regime against the people of Bangladesh. In response, he joined the Birmingham Action Community, mobilising British individuals to participate in protests against the brutal genocide. His active involvement included tasks such as drafting press releases, fundraising, and designing logos for the protests.

"I took pictures of the Birmingham protests and my pictures were showcased in an exhibition in 2017, called the 'London 1971: Unsung Heroes of Bangladesh's Liberation War' convened by Ujjal Das. The exhibition was showcased British Council Library."

Roger uncle became emotional while talking about his meeting with Sheikh Mujibur Rahman in 1972, at the Claridges Hotel in London.

"On December 16, 1971, I heard the news that Bangladesh finally gained victory against the Pakistani government through my radio. I was completely ecstatic, I started to shout "Joy Bangla! Joy Bangla!"

Later on, he heard the news that Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman was freed from the jail and that he was coming to London for a short visit. He, along with his friends from Birmingham Action community decided to meet the Father of the Nation.

"I couldn't believe it that I was able to hold his hand. I can still remember that Bangabandhu told me that I have heard that you guys have worked passionately to ensure that we can gain independence. Thank you for all your hard work. Meeting with the great leader remains one of my most cherished memories in my life."

In 1972, Roger Gwynn came back to Bangladesh, and stayed there for 3 years.

"During my brief stay in Bangladesh, I collaborated with Dr. Zafrullah Chowdhury at his Ganashasthya Kendra and participated in 2-3 healthcare projects," mentioned the photographer.

Gwynn also created a documentary titled "The Year of the Killing," shedding light on the staggering death toll resulting from the 1974 famine in Bangladesh.

In 1975, Roger Gwynn returned to England and began working with the Birmingham Bangladeshi community. During this time, he translated Humayun Ahmed's "Jochona O Jononir Golpo," aiming to impart the true history of the liberation war to the next generation of the Bangladeshi community.

Currently, Roger Gwynn enjoys a retired life in a quaint location in Gloucestershire. His photos from the 1960s have gained widespread attention on social media, capturing the essence of Bangladesh during that era. Gwynn remains steadfast in his love for Bangladesh, believing that his passion for the country will endure as deep and fervent as it was when he first arrived.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments