Rumaan Alam’s third novel is impossible to leave behind

One of my favourite books in the world is Fitzgerald's The Great Gatsby. Not much of this has to do with the usual American dream metaphor. No, I love Gatsby because it is deliciously readable, because it speaks to something fundamental in the individual reader's hopes, fears, habits, those flitting half-thoughts that flicker in the twilight zone between thought and speech or act.

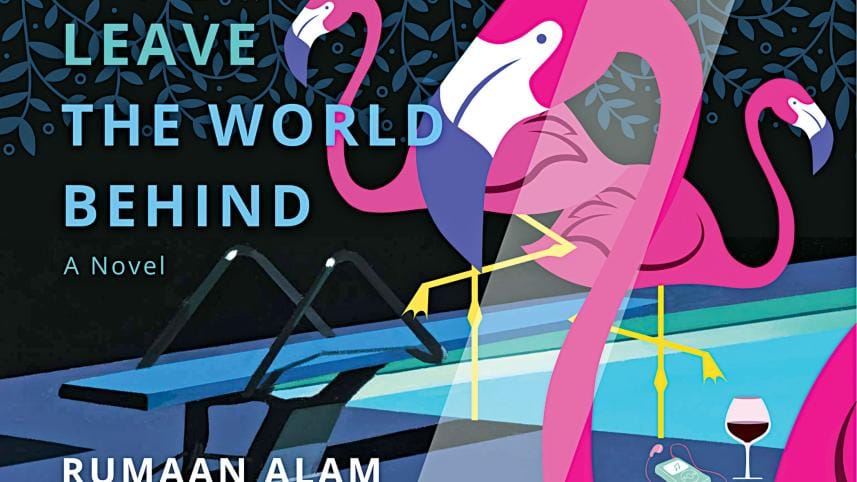

Rumaan Alam's latest novel, Leave The World Behind (Ecco Books, 2020)—which will soon star Julia Roberts and Denzel Washington in a Netflix adaptation directed by Sam Esmail of Mr Robot fame—promises exactly the same experience, except it is crisper and more tense, its concerns a little more mundane and therefore relatable.

Clay and Amanda have booked an Airbnb on a secluded patch of Long Island to vacate with their teenage son and daughter. They have left their cramped New York apartment behind for some respite away from the jobs they're addicted to, the classes Clay teaches and the book reviews he owes to the Times, the work emails Amanda needs to feel needed. They're here to indulge in a house that "ha[s] the hush expensive houses do", owned by people who are "rich enough to be thoughtful." They are a middle class white family, and this is important. When after two days of gorgeously languorous beach time, pool time, ice cream-on-the-couch time an elderly Black couple knock on the door late at night, bringing news of a city-wide blackout in New York, the two families are stuck together in a capsule, deprived even of the mind-saving powers of grocery runs and the internet.

One must, and probably will, read this book with absolutely no idea as to what is about to happen from one paragraph to the next. But fear not for ghosts or psychopathic murderers; the horror of Leave The World Behind is in the prospect that the worst is already happening, as happens in real life, and we are but frogs stewing in a pressure cooker. And so out pop the dormant prejudices, the cowardice, selfishness and courage of human nature shaped by class, race, and tribal instinct.

The downside is that there isn't much in the way of character or plot development, and the interiors of one half of the families feels less deeply explored than the other. The plus side is that the characters are supposed to appear fully baked. This book is more about working out the ingredients that went into the mix and facing discomfort and shame when we recognise parts of ourselves in the characters' responses to danger.

All of which could have been tedious reading in the hands of a lesser writer. But Rumaan Alam just has an easy grace about him that leaks into his prose, lending it humour, edge, and a certain fluidity. He is interested in contradictions—our presumptions of who should own what, in the textures of modern life—"an anticipatory scream, then they met the water with that delicious clash", and in letting the detritus of life under capitalism contribute to character-building—"She bought organic hot dogs and inexpensive buns and the same ketchup everyone bought. […] She bought three pints of Ben & Jerry's politically virtuous ice cream and a Duncan Hines boxed mix for a yellow cake […], because parenthood had taught her that on a vacation's inevitable rainy day you could while away an hour by baking a boxed cake."

These elements of contemporary life are more than props. As the danger begins to make itself more apparent, this relationship of object-consumer is turned on its head, so that we're suddenly forced to reassess what the things we consume stand for in themselves. What is a human being without her access to news and Wifi? What are DVDs and Friends in the absence of human life?

Focusing on these dynamics allows Alam to economise on length and indulge in mood-building, so that one whizzes through the 256 short pages, drinking up the incredibly relatable nuances of what it means to be a mother, a father, grandparents, a Black man, a white woman, a teenage boy, an almost-teenage girl and, above all, alive, which is such a precarious thing to be. Alam, whose Bangladeshi parents moved to the USA in the 1970s, writes through the lens of an American family steeped in American politics and consumerism; but the nuances of his writing resonate far and wide.

Upon arriving at the last page, the reader of Leave The World Behind—just like the reader of Fitzgerald's last lines in Gatsby, ("So we beat on, boats against the current, borne back ceaselessly into the past"), is sent back immediately to the very first page. They are stuck in the loop of its compulsive readability.

Sarah Anjum Bari is editor of Daily Star Books. Reach her at sarah.anjum.bari@gmail.com and @wordsinteal on Instagram and Twitter.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments