Mood mirror

Whenever depression is depicted in pop culture, it is shown in some visible extreme, with blue-grey lighting, dark rooms, ashen faces peering out through rainy windows, bodies curled up in bed. Indeed, in a post-pandemic world, with this relatively recent push for more discourse on mental health coming against centuries of conservative culture repressing or denying the same, it's harder for people with possibly less severe issues to come to terms with their struggles.

Having worked on periodicals for most of my career, I am intimately familiar with that phase of the publication cycle where everything feels like a drag, and if you're in the business long enough, this feeling can seep into other areas of your life. For me, this phase is usually accompanied by insatiable cravings for noodle-based dishes.

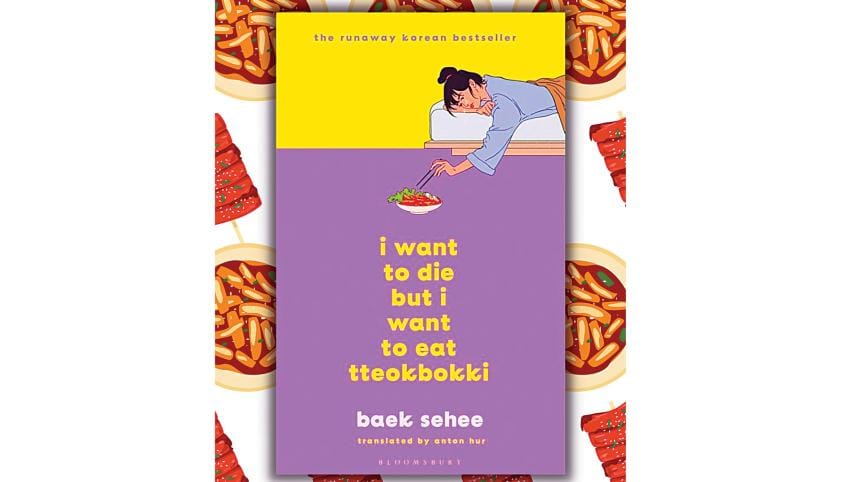

It is because of this quirk that the runaway South Korean hit I Want to Die, But I Want to Eat Tteokbokki by Baek Sehee first caught my eye. That a title would so perfectly capture a nuanced emotion was reason enough for me to want to dive in. I would hear of the hype much later.

This is quite simply, the true account of a person diagnosed with dysthymia (persistent low-grade depression). Along with transcripts from actual conversations Baek Sehee has with her psychiatrist, she provides a short, self-help monologue, usually summarising the latest self discovery, and these are supplemented by more bonus features at the end of the book. There's a short message from the therapist (who also seems to have made some self discovery upon revisiting the transcripts) as well as a number of mini essays covering a range of personal observations.

"I wonder about those like me, who seem totally fine on the outside but are rotting on the inside, where the rot is this vague state of being not-fine and not-devastated at the same time."

Sehee yearns for validation, but has a hard time taking compliments. She is constantly comparing herself to people around her, always falling short of her idealised self, but also finds herself being overtly critical of others, and the awareness of these contradictions often sends her into spirals.

This radical act of public vulnerability is brave enough in this age of social media and the scrutiny it invites, but if one considers just how taboo the topics raised are in the society she comes from, it becomes that much more admirable. The warts-and-all telling not only provides an intimate, unflinching view of a person at their lowest point, it also exposes just how slow, repetitive and messy the process of healing can be. One sees Sehee sliding back to old patterns, exposing some very ugly thoughts, and struggling with discoveries of new dimensions to her illness.

It is also brave of her psychiatrist to have allowed her subject to record these sessions, and to admit that her methods may have been less than perfect. This is the sort of thing that could (and probably would) get her 'cancelled' on social media.

In the author's note, Sehee states that she decided to publish this so that other people out there suffering similar conditions would know that they are not alone, and perhaps be convinced to seek help, just as she did. This best-selling book has sold millions of copies worldwide, been translated into seven Asian languages and made available in English through the translations of Anton Hur, and the overwhelming response has been that people feel 'seen'.

Anyone who has been through low moods and felt the burnout from social pressures and just life, will be able to see themselves in this book, whether or not they have a diagnosed condition or are in need of intervention, and the message is simply this: your feelings are valid. And that's a lot. Is it a fun read? Not at all. But it is definitely an important one.

Sabrina Fatma Ahmad is a writer, journalist, and the founder of Sehri Tales.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments