What exactly were global institutions overseeing?

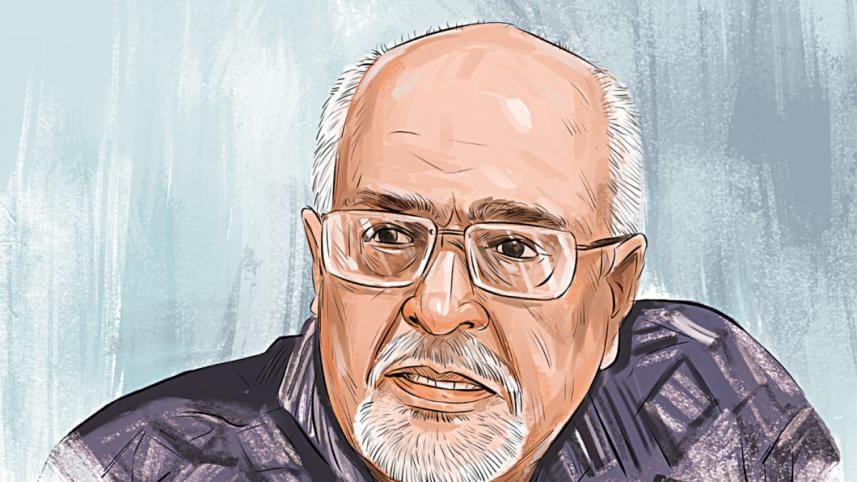

Noted economist Debapriya Bhattacharya raised concerns about the role of global institutions, indicating the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the World Bank (WB), in assessing Bangladesh's debt sustainability under the previous regime as the country faces increasing pressure from escalating debt servicing obligations.

"Where were they, the organisations that were supposed to oversee us? I won't mention names, but they are known by two- or three-letter abbreviations," said Bhattacharya, a distinguished fellow at the Centre for Policy Dialogue (CPD).

"What exactly were they overseeing? How did they verify the data provided by the government? Or were they merely complicit in promoting the so-called development narrative?"

He was speaking at a public lecture titled "Public Debt, Domestic and Foreign: How Much is Too Much?" on the sidelines of the "Annual BIDS Conference on Development 2024", organised by the Bangladesh Institute of Development Studies (BIDS).

"The time has come to identify the people in the government who claimed that we were in a good and comfortable zone," Bhattacharya added.

"It is necessary to determine whether they were misleading the government or if the government compelled them to produce falsified assessments."

He said data on debt is a tricky issue and debt itself is undoubtedly a major challenge, posing one of the most significant challenges at hand.

The debt burden remains a key topic for consideration in the white paper on the state of the economy, said Bhattacharya, who led the panel that prepared the document.

The most misleading aspect was that the past regime presented a fake index for the debt-to-GDP ratio to create a sense of comfort, raising questions over whether or not it was done intentionally.

"It was done to align with the government's development narrative and to make it appear reasonable to secure more foreign loans, suggesting we were in a comfortable zone."

Now, Bangladesh is a de facto defaulter as it has failed to repay $6 billion. Debt servicing liabilities are projected to increase by $1 billion annually, he added.

The government must now assess whether it can afford to take more loans. If not, it should begin negotiations with lenders. The interest period and grace period should also be part of these discussions.

Professor Mustafizur Rahman, another distinguished fellow of the CPD, added: "If you consider public and publicly guaranteed external debt, I believe foreign exchange reserves should also be taken into account."

"For example, in the context of Bangladesh, two years ago, our foreign exchange reserves were $48 billion, while our external debt servicing was $2.3 billion. Now, reserves have dropped to $20 billion, and debt servicing is about $4 billion."

After Bangladesh graduated from a low-income to a lower-middle-income country, it is no longer exclusively eligible for loans with low interest rates and favourable conditions.

As a result, it has opted for higher-interest loans with tougher terms, meaning debt servicing liabilities will continue to increase.

This will become a major issue for Bangladesh in the future, he added.

The significant depreciation of the taka against the US dollar will further exacerbate the situation since revenue from mega-projects is earned in taka but loans must be repaid in dollars, he said.

Syed Moinul Ahsan, professor emeritus of the Department of Economics at Concordia University in Canada, said Bangladesh must increase its tax-to-GDP ratio to tackle the situation.

"The risks are clear. If tax collection does not improve, Bangladesh will face significant challenges in repaying the debt," he added.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments