What does high default loan mean for the economy?

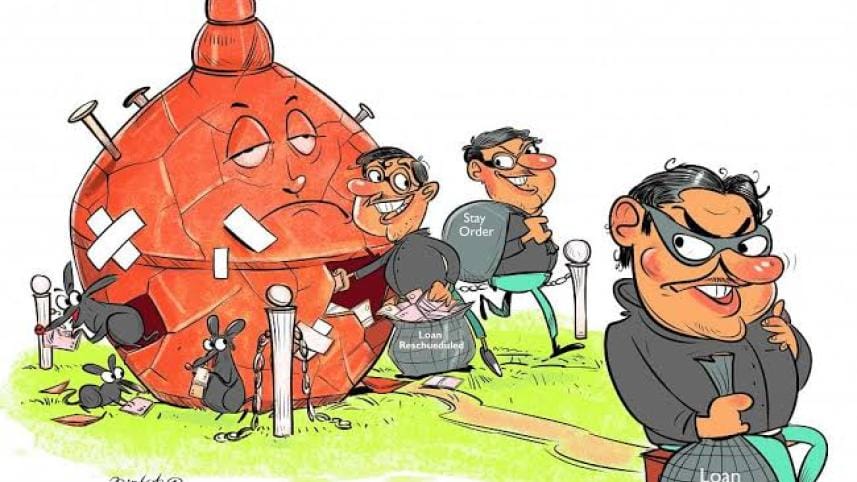

At the end of 2024, one-fifth of the total loans in the banking sector turned into bad loans, mainly because the true extent of fund embezzlement by willful defaulters is now coming to light.

In actual terms, defaulted loans stood at Tk 3,45,765 crore—the highest on record. However, considering distressed assets—including written-off loans, rescheduled loans, and loans tied up in the Money Loan Court—the banking sector's situation is even more alarming, as distressed assets are almost double the amount of bad loans.

It is now evident who is responsible for draining funds from banks and pushing the sector into distress. Bangladesh Bank Governor Ahsan H Mansur has repeatedly said that some politically influential individuals took the funds and laundered them abroad.

In some cases, loans turned bad due to business struggles amid global economic pressure from the Russia-Ukraine war. Banks can absorb such shocks through their own financial strength.

However, it becomes difficult to withstand the surge in bad loans caused by willful defaulters, especially when they operate under political protection.

Who pays the price?

Ultimately, innocent depositors, honest borrowers, and minority shareholders bear the brunt of bad loans.

If the central bank prints money to keep struggling banks afloat or if the government provides budgetary support to state-run banks, taxpayers and the general public suffer.

Before assessing how the burden is distributed, it is crucial to compare Bangladesh's bad loan scenario with that of other countries.

In India, the proportion of bad loans to total loans dropped to 2.5 percent at the end of September 2024, according to the Reserve Bank of India.

The non-performing loan (NPL) ratio was below 5 percent in Vietnam, 8.4 percent in Pakistan, and 3.7 percent in Nepal. Even in crisis-ridden Sri Lanka, the NPL ratio was 12.8 percent.

War-torn Ukraine recorded a 30 percent NPL ratio, while Ghana's stood above 24 percent—both higher than Bangladesh's.

How do rising bad loans impact the economy?

When NPLs increase, banks must keep higher provisions, which directly hit their profitability. Lower profits limit a bank's ability to pay dividends to shareholders.

High NPLs also reduce banks' interest income. To compensate for the loss and continue paying depositors, banks either raise lending rates or lower deposit rates—both of which negatively impact businesses and savers.

While all stakeholders suffer, willful defaulters continue to benefit by siphoning off money without consequences.

The crisis does not end there. Recently, the central bank provided around Tk 22,000 crore in liquidity support to troubled banks to ensure they could meet withdrawal demands.

Such measures come at a significant economic cost, particularly by fueling inflation. Economists strongly criticise these fundings as they have a cascading effect on inflation, but the central bank had little choice to prevent panic in the banking sector.

To keep state-run banks afloat, the government has injected hundreds of crores of taka through the national budget, effectively using taxpayers' money to cover default loans. These funds could have been directed toward education, healthcare, or other essential sectors.

A shrinking credit market

High NPLs also make banks more cautious in lending, limiting access to credit for businesses and individuals. Small and medium enterprises (SMEs), which depend heavily on bank loans, are the worst affected, slowing overall economic growth.

Already, banks are shifting their focus to treasury bonds, as these provide guaranteed returns without the risk of defaults.

Foreign investors and credit rating agencies see high NPL ratios as a sign of systemic risk, discouraging foreign investment and increasing borrowing costs for the country.

"When defaulted loans rise, banks must keep higher provisions, reducing their capacity to issue new loans," said Mustafa K Mujeri, executive director of the Institute for Inclusive Finance and Development.

For instance, a bank has Tk 100 in assets. It gave a loan of Tk 20, which became sour. So it now has Tk 20 worth of defaulted loans, for which it must set aside Tk 20 as provisions. So the bank's capacity for fresh lending comes down to only Tk 60 now.

Moreover, high NPLs incentivise good borrowers to delay repayments, further weakening the financial sector. "With rising bad loans, banks are becoming financially weaker, which ultimately shrinks their contribution to the economy," Mujeri added.

A fragile financial sector with limited credit availability hinders a country's economic development. To address this crisis, the government must take strong measures to control bad loans.

"There should be a concerted effort to prevent new default loans and recover existing ones," Mujeri said.

The way forward

To improve the situation, banks must adopt better governance, enforce legal actions against defaulters, enhance risk management, and strengthen regulatory oversight.

Most importantly, eliminating political influence in the banking sector is crucial for restoring discipline and stability.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments