In this moment of crisis, the poor and needy must be aided with cash support via MFS

Bangladesh has started dealing with the severe consequences of the global coronavirus pandemic in earnest, with curtailed economic activities manifested in factory closures, cancellation of and/or sharply reduced export orders, falling remittance inflows, and depressed demand for domestically produced goods and services.

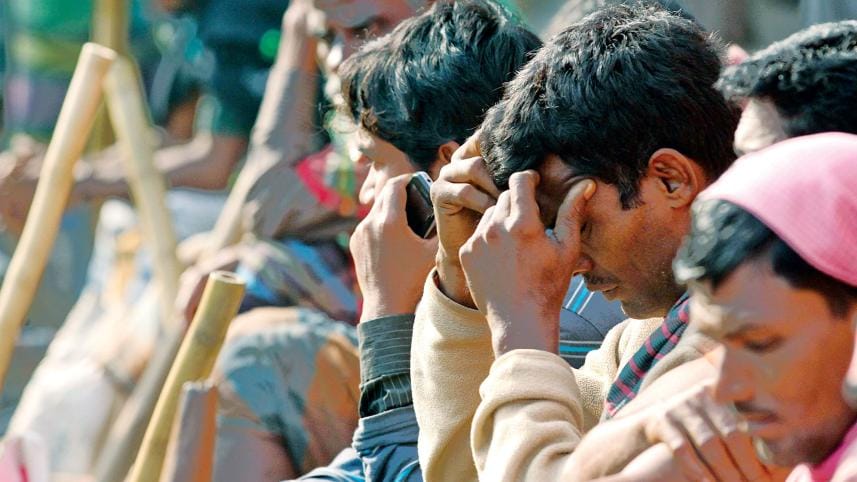

The collapse in external demand coupled with the closure of all economic establishments -- micro, small, medium or large -- due to the lockdown have made millions of workers

The poverty rate has almost doubled to 40 per cent of the population, at least temporarily, reversing all the gains achieved in poverty reduction front over more

To bring about a quick recovery from the collapse, the government has declared a stimulus package of Tk 95,619 crore (3.3 per cent of GDP).

The unfolding extraordinary situation requires extraordinary measures and as such the policy intent of the support measures is quite clear and commendable.

While economic recovery will be of utmost importance as the lockdown eases and the spread of the infection is contained, at this moment the priority should be to provide income support to millions of poor and vulnerable households (including the 'new poor' arising from loss of jobs and earning opportunities) who are now faced with serious livelihood challenges and thus need support.

Hunger and deprivation of bare minimum needs could spark social unrest, potentially undermining our hard-earned socioeconomic progress achieved over the past decades.

Although not an easy task, designing and implementing a comprehensive support system directly targeting the poor and vulnerable groups is not impossible either.

How many people (or, number of households) will need immediate support to stave off hunger and fulfil their minimum needs?

Simulation of falling incomes using the distribution of households around the poverty line seem to suggest that 10–12 million households will require direct support.

How much is needed for the cash transfer programme?

A transfer amount equivalent to the poverty line incomes, which Bangladesh officially uses to make the distinction between poor and non-poor, would require providing each beneficiary household with a monthly amount between Tk 8,500-Tk 11,000.

We take the view that it may not constitute a practical approach not only because budgetary costs would be too high but may also result in perverse incentives for the recipients and attract non-targeted households.

In our view, a much lower monthly cash transfer of Tk 3,000 can be quite an effective support.

This is based on some ground realities as Brac is currently administering such a cash assistance scheme for their identified poor and vulnerable households.

We do acknowledge that this amount is small, but -- based on the expenses related to the basic minimum needs -- this should help the households to survive the crisis.

This amount is unlikely to encourage many non-poor households to seek assistance.

It can be estimated that if a total of 12 million households are to be supported with monthly direct cash assistance of Tk 3,000, the total programme cost for three months will be Tk 10,800 crore, which is calculated as just about 0.36 per cent of Bangladesh's estimated GDP for fiscal 2019-20.

For a longer duration of six months for the same number of households, the computed cost will be is less than 0.75 per cent of GDP.

WHY CASH ASSISTANCE?

We don't undermine the need for in-kind assistance in certain special circumstances.

Otherwise, there exists a huge body of evidence to suggest great advantages of cash transfer programmes over in-kind schemes.

Cash programmes are more efficient as they do not distort consumption choices.

There is evidence that such transfers are 25–30 per cent cheaper than in-kind interventions.

Because of its known advantages, the National Social Security Strategy that Bangladesh adopted in 2015 proposes to transform all workfare-based food transfer interventions into cash assistance schemes.

There is also one more reason for suggesting cash assistance. Given the rapid expansion of mobile financial services (MFS), money can now be sent to even remote places in Bangladesh.

Yearly transactions through MFS exceeded $50 billion in 2019. There are currently about 1 million MFS agents dealing with 80 million registered accounts, of which 35 million are considered active.

The MFS infrastructure thus stands ready to inject the cash cost-effectively while being much less susceptible to corrupt practices.

Under the current social distancing guidelines, it is also exceedingly difficult to distribute in-kind distribution, let alone the proliferation of thefts and misappropriation of relief materials, as reported frequently in media.

Cash assistance is also important to help people keep their consumption as diversified as possible. This can sustain local-level demand for diversified goods and services.

Otherwise, many small growers of such items as vegetables, fruits, eggs and dairy products will go out of business.

HOW TO REACH OUT TO THE BENEFICIARIES?

The National Social Security Strategy called for a national household database to identify the poorest and vulnerable populations groups.

However, even after several years, the proposed mechanism could not be established.

Therefore, using a nationwide database to track and reach the needy households at this time of crisis would remain a missed opportunity.

International experiences drawn from Brazil, Chile, India, Malaysia, Pakistan, Peru, the Philippines, Thailand, and from many other countries seem to suggest cash assistance delivered directly through digital financial services work in an extremely efficient manner.

The basic principle of our proposed approach is to set up an Emergency Cash Allowance Programme (ECAP) for 10–12 million households.

Households in need of assistance should self-identify or self-register for the allowances.

They can register by sending SMS to dedicated mobile numbers. The registration process should be simple enough so that most potential beneficiaries can apply without needing much assistance.

During the registration, they should provide names of the household head and household members along with their NID numbers, family address, and information on their preferred MFS account for making payments.

Payments should be made through mobile phone accounts using any MFS providers of their choice such as bKash, Rocket, Nagad, SureCash, etc.

If households need assistance in registering, they may use the services of more than one million MFS agents scattered across the country. It is possible that many applicants currently do not have MFS accounts.

However, since e-KYC is currently in operation in Bangladesh, opening such accounts using NIDs takes only a few minutes.

It is possible that certain beneficiaries either do not have their NIDs or have misplaced/lost them.

Under those circumstances, they may be registered using their birth certificates.

Opening of e-KYC accounts without NIDs can be temporarily allowed—as is the case with the garment workers -- and these accounts, if needed, can be terminated later.

There are already some solid examples of the currently existing MFS infrastructure being an efficient means of delivering cash transfers.

Between 6 and 20 April, about 2.6 million garment workers could open their MFS accounts to receive their salaries.

Under a social security scheme, the Primary Education Stipend Programme (PESP), some 14.4 million primary students are enrolled and their 10 million-plus mothers receive monthly allowances through MFS.

Therefore, opening accounts using MFS and delivering cash assistance are already well-established in the country.

Introducing a perfect system for cash transfer perhaps will not be possible.

We have to acknowledge some scope of leakages/mistargeting. That is why we suggest that a relatively low amount of transfer be made each month.

Given the low financial literacy of most of our poor people, regular monthly payments could help with better management of household cash flow.

The measures suggested above may need further refinements to make them operational, but certainly doable.

Finally, the proposed cash assistance programme should be regarded as complementary to already declared intervention measures.

The expansion of the safety net programmes, as already announced by the government, should be implemented in addition to this cash assistance programme to make the support system more impactful.

Time is of the essence here in delivering critical support to the poor and needy.

The proposal outlined here shows that implementing a vast cash assistance programme -- to meet the basic needs of 50 million people (including family members) -- is very much within our fiscal and technological means and thus should be pursued immediately.

The current government deserves a lot of credit for expanding the MFS in Bangladesh, and it would only be most timely and appropriate for it to use the infrastructure to provide the prompt livelihood support that people need.

Ahsan H Mansur, executive director, Abdur Razzaque, research director and Bazlul Khondker, director of the Policy Research Institute of Bangladesh (PRI). This article is produced as part of PRI's Policy Advocacy Initiative on Digital Financial Services in Bangladesh.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments