Hue and cry for onion: some insights

Onion price hike has been one of the most discussed issues for the last couple of months. As onion is an essential daily food ingredient, the issue of price hike has extended hue and cry among all types of households, rich or poor. While people are dissatisfied with the continuation of high price, the solution seems to be a far cry.

Many people believe that a “syndicate” prevails in the market, without even understanding what syndication means. However, according to a study conducted by the Bangladesh Institute of Development Studies (BIDS) with support from the Competition Commission, collusion or so called “syndication” is not possible in the onion market.

Effective policy and market intervention to stabilise price of essential agricultural products depend on proper understanding of the value chain of a product and the actors involved and their power to distort competition in the market. If price volatility is associated with sub-optimal level of competition in the market, correction to price volatility could be managed by bringing more competition in the markets. Often, it has been difficult to understand reasons behind price volatility because of a lack of correct insight on various actors and their roles. Roles of different actors actually frame the level of competition. If there is a lack in competition, certain groups of actors can influence the market.

The study, carried out in 2018, reveals that around 60 percent of the yearly consumption of onion is locally produced and the remaining 40 percent is imported. Around 80 percent of the imported onion comes from India. Therefore, the onion market in Bangladesh is strongly linked with the market in India. Thus, any shock in the Indian market is transmitted quickly to the onion market in Bangladesh.

Although India is a large producer of onion, its supply is often affected due to weather factors and price of onion in India is also politically-sensitive. Whenever local price of onion goes up, the Indian government imposes restriction on onion export in several ways: banning export and setting minimum export prices at a very high level to make onion import prohibitively costlier. When the local market stabilises and price returns to normal level, the trade restriction is lifted. Such actions extend heavy impact on onion price, part of which is for supply shock and part is for inflationary expectation.

The analysis reveals that consumption of onion also increases with the level of income. People of the lowest income earning 10 percent of the population consume 1.3 kg onion per month. The consumption is 5.3kg per month for the highest income group. Urban people consume more onion on an average compared to rural people. Onion comprises only small proportion of food expenditure (1.1 percent to 1.6 percent of monthly food expenditure of households). If we sum up these information, it may be noted that a rise in price of onion is not a big concern for higher income group as this comprises a tiny proportion of their food expenditure. But it is a concern for poor people and especially the poor people in urban areas. Therefore, any price stabilisation initiative for onion should target the urban poor at first.

Onion prices usually go up in the last four months of a calendar year (starting from September) as the harvesting period is March-April, starting from February in many areas. The retail-wholesale price gap exhibits high variability for local onion variety but relatively stable for imported onion.

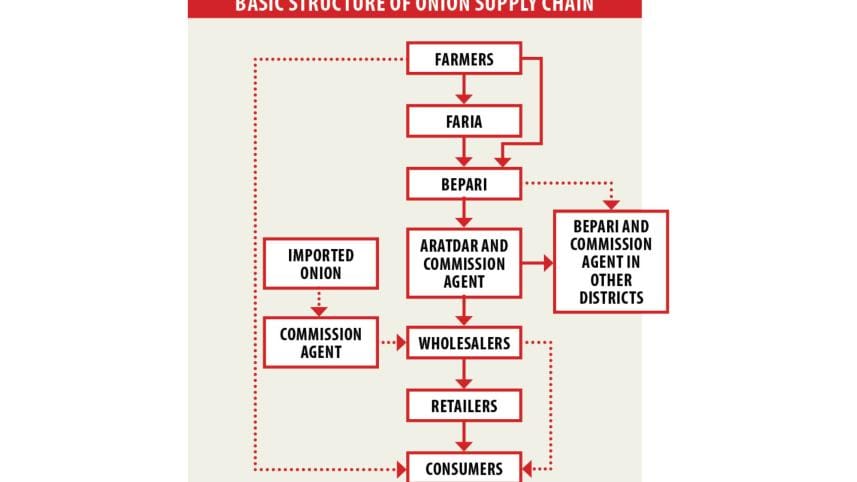

There is no uniform market structure for onion that fits all places and regions across the country. Instead, the supply chain exhibits variation across regions and markets. The supply chain in the onion-growing region is relatively simple than the supply chain between growing and non-growing regions. More actors are added when onion moves from growing to non-growing regions and commission agents with large investment play a big role in linking actors of growing regions and the consuming regions. Importers also play a key role in the supply chain. Commission agents link importers to traders in large markets in big cities.

Our study did not find any clear indication of anti-competitive behaviour in the onion market. It appears that there are significant number of buyers and sellers in the market and entry into the market is not prohibitively costly in most of the stages in the supply chain. It is rather the inherent structure of the onion market that assigns high value to experience and market knowledge. Neither is there any strong evidence of collusive price-setting in major markets, nor does it turn out that traders are information-constrained regarding the essentials of the market. The role of traders’ association is largely non-existent. In brief, the onion market appears to hold most of the pre-conditions for a competitive market.

The occasional price volatility is mainly caused by natural forces of demand and supply in the market. As apparently there is no sign of oligopoly or cartel in the onion market, the role for an organisation like the Competition Commission is not going to be that much effective in the short-run to stabilise the market. Rather, government intervention in terms of import well ahead of slack season of onion and festivals could prove to be much better strategy to stabilise onion price.

Let us try to explain the causes of this year’s increase in onion price. Our study recommended that the government observe and monitor the production and price of onion both inside the country and in India, especially before the beginning of the slack season. There was clear lack in such monitoring and forecasting on part of the government. There was poor harvest in India, and we cannot expect that India would export onion (to Bangladesh) by depriving their own citizens. There was already a tendency of rise in price in Bangladesh at the end of the season. Once India imposed a ban on onion export, the information sparked speculation among both sellers and buyers of onion regarding price hike.

The price spiral got fumed with inflationary expectation of the onion price with natural forces of supply and demand. Even the rich people started distress purchase without even noticing that onion constitutes a tiny share of their expenditure. However, the real hardship of the onion price hike fall on the low-income people. If the government had encouraged import of onion earlier, noting the poor harvest in India, the rapid price surge could be halted. When the decision came, it was too late. Also, the open market sale at a lower price was necessary at a larger scale. Then came the search for syndicate in the onion market, which is non-existent.

Hoarding by some actors is a very common tendency during a situation of supply shock. But the hoarding is not possible for a long period. The government needs to intervene in the market at the right time through import and low-price sale, rather than wasting time and resources in search of a “syndicate”. We should not forget the natural forces of supply-demand interaction and inflationary pressure.

At this moment it is hard to stabilise the price and we will have to wait till the new harvest to stabilise the market. The onion import in the pipeline will not be able to stabilise the market to a large extent as the cost of import from distant sources is higher than the cost of import from India. In the meantime, the government needs to continue with the open market sale to support the poor people.

Going forward, initiatives should be taken to increase the productivity of onion. High-yield variety onion seed should be made available to farmers at proper time to increase the production. Onion is a commercial crop, so production strategy needs to be developed in order to increase the production at state level. Special initiatives could be taken to produce high-yield varieties in flat lands of hilly regions. Even during the dry season, onion could be produced in haor (low lands in Sylhet region) areas.

Seed treatment and selection of the variety are important technical practices for increasing the yield of onion which was not realised by farmers. Hence, the extension agencies should take up suitable training programme on these aspects so that farmers are properly educated.

During the time of sudden increase of price, government intervention in terms of low-cost open market sale has to be undertaken mainly targeting the urban poor. Sources other than India should be explored to import onion. Onion may be imported more from China, Turkey, Pakistan, Myanmar and the Netherlands (especially during the period of July-November).

Memorandum of understanding could be signed with the State Trading Corporation, India and some important essential commodities could be imported at government-to-government level arrangement.

The authors are respectively senior research fellow and research fellow at the Bangladesh Institute of Development Studies.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments