Annual inflation hits 12-year high despite easing in June

The annual average price spike in Bangladesh surged to its highest level in 12 years in the just-concluded fiscal year despite easing in June, reflecting the persistent erosion of real income and the deterioration of the living standards of low-income groups.

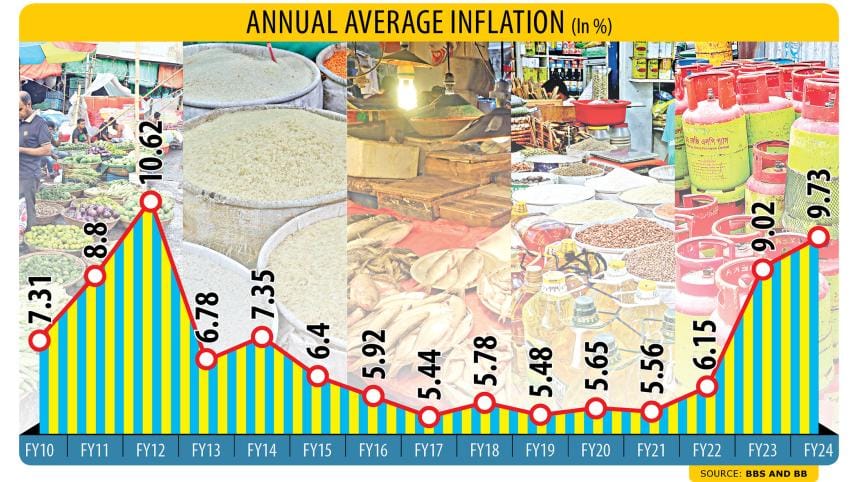

Annual inflation rose to 9.73 percent in 2023-24, the highest since 2011-12 when it was 10.62 percent, overshooting the government's target of containing it to 7.5 percent, according to the Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics (BBS).

This is the second year the Consumer Prices Index, a measure of the increase in the prices of a basket of products and services, stood at more than 9 percent – a sign of sterility of the measures by the government and the central bank to contain prices.

"Inflation has been very high in the last two years, and policies were not taken at the right time and were unsuccessful," said Selim Raihan, executive director at the South Asian Network on Economic Modeling.

He blamed multiple failures. "There has been policy failure and there has been coordination and management failure."

Raihan, also a professor of economics at the University of Dhaka, said there is a huge imperfection in the market system.

"A section of businesses can see that the government is failing to regulate the market. Many of the businesses are also connected politically. There are also anomalies in the data related to supply, demand and production. Such information is not credible."

Inflation has persisted over 9 percent since March 2023. And except for monthly fluctuations, the rate has crossed 9.5 percent since January.

In June, inflation declined to 9.72 percent from 9.89 percent in May thanks to the decline in food and non-food prices. Inflation was 9.74 percent in April, BBS data showed.

Food inflation slipped to 10.42 percent last month from 10.76 percent a month ago. The non-food price growth slowed to 9.15 percent from 9.19 percent.

"We saw some fluctuations in the last several months. However, we have not witnessed a consistent downward trend," Prof Raihan said.

"It can be said that inflation is easing if there is a consistent decline," said MK Mujeri, a former director-general of the Bangladesh Institute of Development Studies.

In its report following the second review of the $4.7 billion loan programme for Bangladesh in June, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) said higher inflation levels were mainly due to persistently strong high inflation expectations and the anticipated depreciation of the exchange rate.

The taka has lost its value by about 35 percent against the US dollar in the past two years, making imports costlier.

The Bangladesh Bank hiked the policy rate, the interest rate at which it lends to conventional banks, by 50 basis points (bps) to 8.5 percent on May 8 to tighten the money supply. In total, it has raised the rate by 400bps in the past two years.

It also made the lending rate in the banking sector completely market-based after four years and adopted a flexible exchange rate mechanism by allowing the dollar to trade within a band.

"However, the measures were not taken at the right. Therefore, they did not bring about the desired results," Prof Raihan said.

The IMF has suggested that the policy rate increase to a peak of 9 percent by the middle of the current fiscal year in order to tame inflation to 7 percent by the end of 2024-25 on the back of the continued tighter policy mix and projected lower global food and commodity prices.

"Should external and inflationary pressures intensify, a further tightening in policies is warranted," it added.

Ahsan H Mansur, executive director of the Policy Research Institute of Bangladesh, expects inflation to come down in the months ahead.

"You should give at least six months."

The former economist at the IMF recommended the central bank raise the policy rate to 10 percent, if required.

The central bank is expected to announce the monetary policy for July-December later this month.

Will monetary tightening be enough?

Demand containment measures through monetary tightening alone might not work when it comes to curbing inflation. This is because there are a lot of distortions in the market and problems in the supply chain.

Both Raihan and Mujeri suggest the authorities address these issues.

Prof Raihan said initially, it was said that external factors such as the supply disruption caused by the lingering impacts of the coronavirus pandemic and the Russia-Ukraine war were behind the inflation spike in Bangladesh.

"The same can't be said now," he said, referring to many countries' success in reducing inflation although the two factors are still in play while the Middle East crisis has emerged as a new challenge.

Mujeri said there are actors in the supply chain who can influence the market and prices.

"They are abusing their market power. Thus, attention should be given to remove these weaknesses. Engaging law-enforcing agencies may work temporarily, but it is not a sustainable solution."

Are govt interventions enough to protect the poor?

Mujeri said the high inflation has caused a massive erosion of people's real income.

"It hurts low-income people. But there is a shortcoming at the policy level in admitting this."

He urged the government to expand the coverage and allocation for social protection to support the poor until prices fall.

The government distributed 32.6 lakh tonnes of foodgrains in the last fiscal year, an increase of 13 percent from a year ago, food ministry data showed.

It plans to distribute 30.3 lakh tonnes of rice and wheat in FY25. Besides, the government is selling some essential food items at subsidised rates among one crore families.

"The government's intervention should continue. This will not make the poor richer. However, it will allow them to survive," added Mansur.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments