What is riding on remittance?

Thinking about the role of remittance in our economy often makes us think about growth and standard of living.

Driven by such thoughts, we tend to subscribe easily to statements such as “Bangladesh economy rides on remittances”. In what sense is this statement true and in what sense is it not, or just partially, true?

Surely, it cannot be the standard of living. The most widely used measure of a nation’s standard of living is annual per capita income.

Last fiscal year, remittances added about a $100 to our $1,795 (as reported by the Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics) per capita GDP. This constituted 5.5 per cent of GDP per capita, which is not trivial. But it certainly is not a ride.

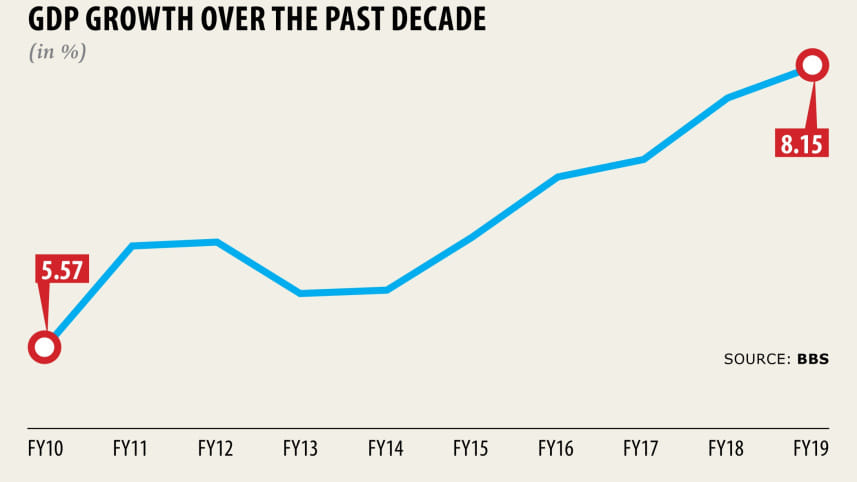

Arguably, remittance contributes to GDP growth itself. There is no consensus on the magnitude and direction of the impact of remittances on GDP growth.

However, the weight of evidence appears to favour a positive impact of remittances on growth, according to many different studies at the national and international levels.

The impact of 1 percentage point increase in the remittance share of GDP on per capita GDP growth can range between 0.12 to 0.74 percentage points.

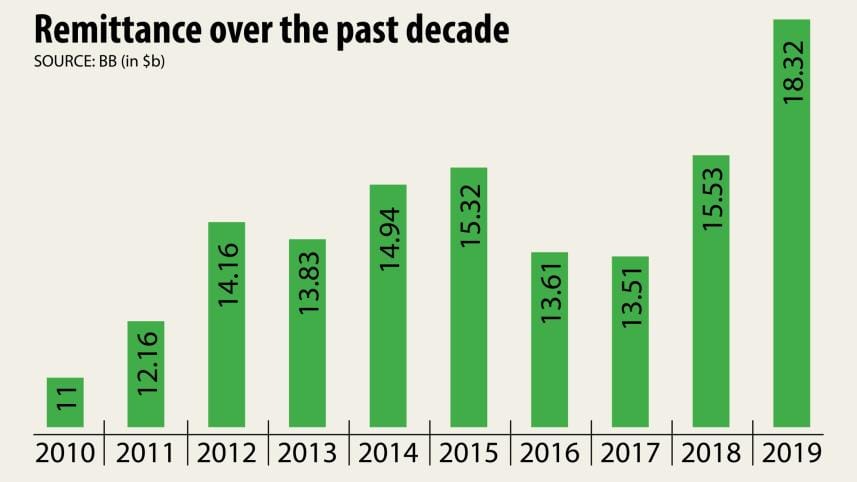

In Bangladesh, it is very unusual for remittance-GDP ratio to rise by close to 1 per cent of GDP in any given year. In fact, the ratio has been declining since fiscal 2013-14.

While the decline may be reversed this year, recent trend in the remittance-GDP ratio hardly justifies the conclusion that GDP growth rides on remittances.

Had that been so, we would have seen a drastic fall in the GDP growth rate in fiscal 2016-17 when the remittance-GDP ratio declined from 8.1 percent in fiscal 2014-15 to 5.3 per cent in fiscal 2016-17.

Officially reported GDP growth however increased from 6.6 per cent in fiscal 2014-15 to 7.3 per cent in fiscal 2016-17.

Remittances serve as an automatic stabiliser as well.

Studies show that remittances tend to rise during downturn phases in the economic cycle. Migrants send more money home to support their financially distressed families.

Remittances smooth consumption and contribute to the stability in the standard of living of the recipient families.

In contrast, other private financial flows frequently move pro-cyclically, raising income in good times and decreasing it in bad times.

The hypothesis of remittances being countercyclical is based on the evidence that a large portion of remittance transfers are intended for altruistic purposes or as part of an insurance arrangement under which migrant workers send more money when the family back home are hit by an adverse income or expenditure shock.

The fact that remittances rise sharply after natural disasters in Bangladesh is consistent with this view. This can partly explain why remittances are currently booming after reaching a historic high last year.

Not that the capacity to remit due to changing conditions in the host countries, cash subsidy and exchange rate depreciation (however small) have not played any role, but the slowdown evident from all growth and employment related indicators may also be playing a major role in boosting remittances this year.

The growth and consumption stabilisation roles of remittances pale when compared with the role remittances play in our balance of payments and the financial system.

Remittances finance a very large chunk of our external deficit. Understanding this requires a small digression into the details of the balance of payments.

Merchandise trade and services balance is the difference between the dollar value of sales of our goods and services to foreigners and purchases of goods and services from foreigners during a year.

This difference is called “resource balance” in the national accounts or net exports in economics textbooks.

When purchase exceed sales, we have an external resource deficit. This is equivalent to having domestic saving below domestic investment.

Net exports is always equivalent to the difference between savings and investment from an accounting perspective.

Movements in interest rates, exchange rates, prices and income ensure that the decisions to export and import and to save and invest made by a wide variety of economic agents match in the aggregate.

In Bangladesh, the excess of purchase over sales has increased from $10.1 billion in fiscal 2012-13 to $19.2 billion in fiscal 2018-19.

In addition, we typically have deficit in the income account, comprising of profit repatriation by foreign investors and interest payments on external public debt.

This increased from about $2.4 billion in fiscal 2012-13 to $2.9 billion in fiscal 2018-19. Both of these deficits needed financing.

Remittances from our workers abroad was more than sufficient to cover these deficits until fiscal 2015-16.

This, together with surplus in the financial account resulting from official medium and long-term borrowing from the development partners and short-term foreign borrowing by the private sector, contributed to rapid accumulation of foreign reserves.

Although remittances fell short of external resource and income deficit since fiscal 2015-16, it still covered a sizable part: nearly 75 per cent of the deficits in fiscal 2018-19 after reaching a low coverage ratio of about 60 per cent in fiscal 2017-18.

Remittances have covered 84 per cent of the external resources and income deficit in the July-November period of this fiscal year.

Our financial indebtedness to the rest of the world would surely have grown a lot faster if, fluctuations notwithstanding, such a large volume of remittance money were not flowing in year after year.

It helps finance our trade imbalance without excessively incurring costly obligations to pay in future for such finance.

This role would have been even bigger had there been no diversion of remittances to finance reverse flows -- a euphemism for flight of capital through informal channels from Bangladesh.

There is some evidence suggesting that about 13–14 per cent of remittances are diverted to finance reverse flows.

Remittances contribute to augmentation of liquidity in the financial system. It’s a source of both dollar liquidity in the foreign exchange market and taka liquidity in the money market as remittance dollars get converted into takas.

Daily trading volume in the foreign exchange market varies a great deal but it most likely averages around $200 million, while average daily remittances is about $45 million (based on fiscal 2018-19 inflows), constituting 22.5 per cent of the average daily foreign exchange trades.

Total remittance inflow in fiscal 2018-19 constituted 11.9 per cent of total deposit at the end of June last year.

Safe to say that the exchange rate would have been much harder to maintain at its current level and the interest rates would most likely have been even higher in the absence of remittances.

These macroeconomic roles of remittances are what earns it “the economy rides on” label.

What really rides is our external stability as manifested in the level of foreign exchange reserves and the exchange rate as well as financial intermediation through deposit and, consequently, credit creation.

Its role in GDP growth and income generation is much smaller, but it does contribute to keeping consumption stable in the face of fluctuating incomes.

The author is an economist

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments