Puzzling low tax-GDP ratio

While official data portrays the burgeoning growth of Bangladesh's economy, tax collection relative to the gross domestic product (GDP), a measure of the size of the economy, shows an almost opposite trend.

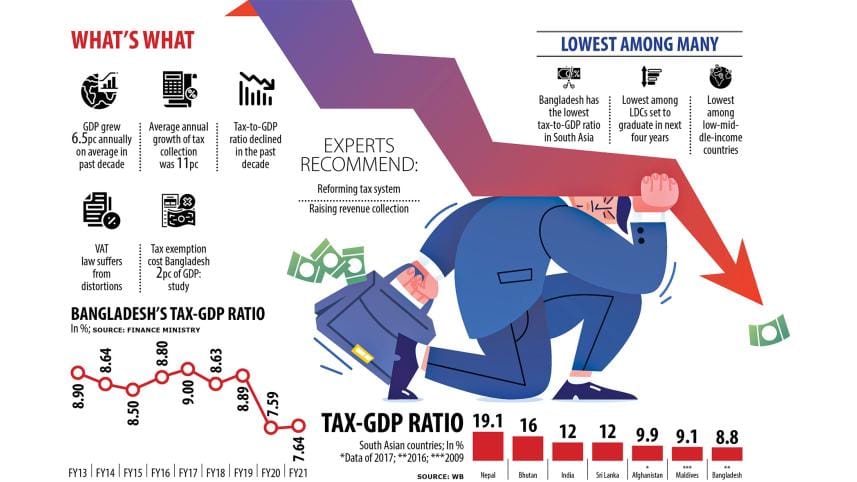

The tax collection as a percentage of GDP has been stuck at around 7.6 per cent, the lowest in South Asia and one of the lowest in the world. This prompts economists to question the disconnect since revenue receipts should increase in line with the expansion of the economy.

"This shows a big mismatch," said Selim Raihan, executive director of the South Asian Network on Economic Modeling.

"It shows that there is no relation between GDP growth and revenue collection although the tax-to-GDP ratio increases in other countries because of the growth of the economy. In the case of Bangladesh, it is a puzzle."

Over the past decade, the GDP grew 6.5 per cent annually, on average. The average annual growth of tax collection was 11 per cent.

As a result, Bangladesh continues to languish at the bottom among the South Asian countries when it comes to the tax-to-GDP ratio.

Among the least-developed countries set to graduate to the developing nations' category in the next four years, Bangladesh has the lowest tax collection as a percentage of GDP, data from the World Bank showed.

Bangladesh's tax-to-GDP ratio is also the lowest among the low-middle-income countries, and the ratio declined in the past decade, according to Raihan, also a professor of economics at the University of Dhaka.

"Does it mean that the additional GDP growth has remained out of the tax net? Does it mean that the economy has become more informal? Is it that tax avoidance is encouraged? It is a puzzle," he said.

The new value-added tax law, which came into effect several years ago, suffers from distortions while a large number of people are exempted from tax payments.

For example, the garment and textile sector, which provides guaranteed income, enjoys just half the corporate tax rate applied to non-listed companies.

Citing a previous study he co-authored, Prof Raihan says tax exemptions cost Bangladesh 2 per cent of its GDP.

"We have also had serious problems in the execution of laws. There are also a large number of people who don't want reforms. It seems that there is a nexus among a section of taxpayers and revenue officials against reforms."

However, this may not be the only case.

Economists are, in fact, doubtful about the GDP growth estimates in the first place, since the growth numbers do not commensurate with the real data such as revenue collection, debt, export-import, and credit growth.

"The growth that is shown does not relate with reality because an overstatement emerges if GDP is compared with other data," said Zahid Hussain, a former lead economist of the World Bank's Dhaka office.

Besides, the tax base is low compared to the size of the economy. Collection efficiency is also low. There are many loopholes in the tax policies, he added.

"As a result, small fishes escape the tax net, which is also not strong enough to catch big fishes."

In Bangladesh, there are plenty of tax benefits under various names: holidays, exemptions and waivers. So, Bangladesh loses a huge amount of tax because of the prevalence of tax breaks.

"The fact is money is really going out of taxpayers' pockets. But it is not going to the state coffer. The money is going to the pockets of various intermediaries [tax lawyers, dishonest revenue officials] in the system," Hussain said.

So, if the lost revenue is taken into account, the tax-to-GDP ratio would have increased.

"No country will be able to become an upper-middle-income country with such a low tax-to-GDP ratio," said Ahsan H Mansur, executive director of the Policy Research Institute of Bangladesh.

"The tax-GDP ratio should be 16-17 per cent."

He says the failure to increase tax collection is affecting the whole fiscal management.

People's out-of-pocket expenditure is increasing for a lack of public investment in the healthcare sector and many families go broke because of higher medical expenses. Similarly, Bangladesh cannot ensure quality education for inadequate investment.

"We have to borrow to build infrastructure and that loan is increasing at a higher rate," Mansur said. "There is no room for comfort if we can't invest from our own sources and have to run by borrowing."

At a programme in Dhaka on Saturday, Debapriya Bhattacharya, a distinguished fellow at the Centre for Policy Dialogue, said Bangladesh is a country of 16.50 crore people and 74 lakh people have tax identification numbers. Of them, only 23 lakh file income tax returns.

"Why hasn't the number of taxpayers gone up? If per capita GDP has increased, then why don't people pay taxes?" he questioned.

Mansur, also a former economist of the International Monetary Fund, suggests reforming the tax system.

"It appears that political will for reforms is low. But without increasing revenue collection, it is not possible to fulfil the expectations of the people and the government. Politicians have to realise this."

Increased revenue collection is also needed to become a developed nation.

"Our economic growth will slow if we can't invest in physical and social infrastructures. Income distribution will be more skewed if we can't boost tax collection as tax policy is a tool for ensuring better income distribution," added Mansur.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments