The power of Qasidas and devotional poetry in deepening Ramadan reflections

When Rumi says,

"The wound is the place where the Light enters you.

So don't be afraid of your wounds.

In your pain, there is a path to joy,

A beautiful path, a holy path"

Or when Hafiz, in The Laughing Heart, reminds us—

"Even if you've broken your vows a thousand times,

Come back to the center of your heart.

Be like a tree and let the dead leaves drop.

Don't grieve, anything you lose will come in a different form"

—the heart of the reader, the heart of the believer, is stirred with spirituality, emotion, and the urge to get closer to the Almighty. These verses express the deep yearnings of the soul, words that many wish to utter but often do not know how. They give voice to the silent longings of the heart, making tangible the ineffable pull toward divine love and mercy.

During Ramadan, a month dedicated to worship through fasting, prayer, and the recitation of the Quran, these spiritual emotions become even more pronounced. While these core acts of devotion take center stage, qasidas (Islamic odes) and devotional poetry serve as powerful complements, enriching the experience of Ramadan and deepening one's spiritual reflections. These poetic expressions, deeply rooted in Islamic tradition, act as a bridge between the soul and the Divine, fostering mindfulness, reinforcing faith, and evoking profound emotions of love, repentance, and surrender. From the timeless Qasida al-Burda to the mystical verses of Rumi, Hafiz and many more, such poetry offers believers a heightened sense of devotion, contemplation, and communal connection throughout the sacred month.

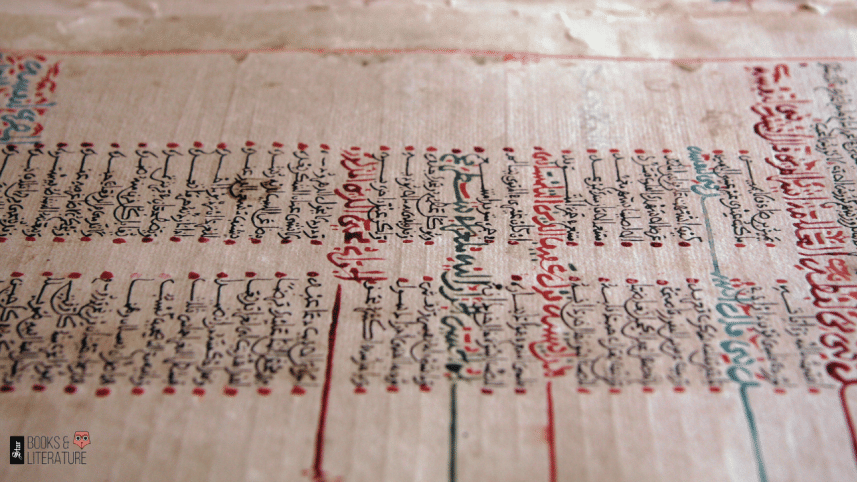

The term "qasida" originates from the Arabic word "qasad", meaning intention or purpose. Historically, qasidas are long-form poems that originated in pre-Islamic Arabia, often exceeding 50 lines. They were traditionally used to praise patrons and rulers, or to convey moral and ethical themes. With the spread of Islam, the qasida form was adopted and adapted across various cultures, including Persian and South Asian societies. In the Indian subcontinent, qasidas were initially composed to laud Mughal emperors and local nawabs. However, as political dynamics shifted, especially with the advent of British colonial rule, the content of qasidas transitioned to focus more on religious themes, particularly extolling the virtues of Ramadan, the teachings of Islam, and praising the prophet (PBUH).

If you are from areas like Faridpur, Old Dhaka (Puran Dhaka), Khilgaon, or other parts of Dhaka, you might recall the melodious qasidas sung during the pre-dawn hours of Ramadan. Groups of volunteers, often young enthusiasts, would traverse the narrow lanes, singing spiritual verses to awaken the faithful for sehri, the pre-fast meal. These soulful renditions, rich in devotion and cultural heritage, served both as a wake-up call and a means to instill a sense of community and spirituality. The qasida tradition in Bangladesh traces its roots back to the Mughal era. Introduced by Persian influences, qasidas were initially composed in Persian, the court language of the Mughals, and were performed to praise emperors and noble figures. As time progressed, especially after the decline of the Mughal Empire, the themes of qasidas shifted towards religious devotion, particularly during the holy month of Ramadan. However, with modern conveniences like alarm clocks and changing lifestyles, this beautiful tradition has seen a decline over the past few decades. Yet, in some neighborhoods of Dhaka and other parts of Bangladesh, dedicated individuals strive to keep this heritage alive, blending cultural nuances unique to the region.

One of the most renowned qasidas in Islamic literature is the "Qasida al-Burda" (Poem of the Mantle) by Imam al-Busiri. Composed in the 13th century, this poem praises the Prophet Muhammad (peace be upon him) and has been revered across the Muslim world for its spiritual depth and poetic excellence. A notable verse from the poem states:

"He is the sun of virtue, the others are but stars that give light when the sun has set."

This line metaphorically elevates the Prophet's status, emphasising his unparalleled virtue and guidance. The "Qasida al-Burda" has been translated into numerous languages and is often recited in religious gatherings, especially during Ramadan, to inspire devotion and reflection.

Islamic devotional poetry has long served as a medium for exploring divine love, self-reflection, and the transient nature of worldly attachments. From classical Arabic qasidas to Persian and Urdu poetry, this literary tradition has provided believers with a way to articulate their deepest spiritual yearnings. Poetry, with its rhythmic flow and profound metaphors, transcends mere words; it becomes an intimate conversation between the soul and the Divine. Whether recited in solitude or as part of communal gatherings, these verses foster a deep connection with faith, enhancing the Ramadan experience through reflection, gratitude, and devotion.

One of the most significant poetic forms within Islamic tradition is the ghazal, which originated in 7th-century Arabia and evolved from longer pre-Islamic odes. Typically composed of independent yet thematically connected couplets, ghazals often express themes of love, loss, and the longing for spiritual fulfilment. While at times mistaken for romantic poetry, many of these verses serve as metaphors for the soul's journey toward Allah. In this way, poetry is not just an artistic expression but a spiritual tool, one that helps believers navigate their relationship with both the earthly and the divine. A central theme in Islamic poetry is 'Ishq-e-Haqiqi', or true divine love, which describes the deep yearning of the soul to be united with its Creator. Many poets use imagery of separation and longing to depict this spiritual journey, mirroring the believer's struggle to attain closeness to Allah. Rumi's verses often reflect this idea, emphasising that the trials and wounds one endures in life are, in fact, openings through which divine light can enter the heart. His famous lines, "The wound is the place where the Light enters you. So don't be afraid of your wounds," remind believers that even in hardship, there is a divine purpose. Ramadan, as a month of self-discipline and purification, is an ideal time to embrace this perspective, viewing fasting and sacrifice as a means to cleanse the heart and strengthen one's relationship with Allah.

Alongside divine love, 'Ishq-e-Majazi', or metaphorical love, is another key theme in devotional poetry. This refers to earthly love, which often serves as a reflection of the greater, eternal love for the Divine. By contemplating human relationships, poets express lessons of devotion, patience, and surrender—qualities that are essential in one's spiritual journey. Hafiz's poetry beautifully captures this sentiment, reminding believers that love, whether worldly or divine, should be approached with trust and surrender. His lines, "Even after all this time, the sun never says to the earth, 'You owe me.' Look what happens with a love like that—it lights the whole sky," highlight the selfless and boundless nature of divine love, resonating deeply with the spirit of Ramadan.

Whether through Rumi's reflections, Hafiz's joyous surrender, or Iqbal's uplifting verses, poetry reminds believers of faith's beauty and purpose. Iqbal's words, "Elevate yourself so high that even fate must ask you what you desire," reflect Ramadan's transformative journey, one of discipline, humility, and divine connection. In South Asia, devotional poetry has merged with cultural traditions, making it a celebrated part of religious expression. In Bangladesh, Pakistan, and India, it often accompanies qawwali music, making spiritual teachings more engaging and communal. In Old Dhaka, Ramadan nights once echoed with qasida competitions, where young performers were awarded medals for their performance, wearing them with pride on Eid-ul-Fitr. This tradition turned poetry into more than just words, it became a celebration of faith, a communal act of devotion, and a bridge between literature and spirituality.

Poetry has always been more than just an art form in the Islamic tradition, it is a bridge between the heart and the Divine, a vessel for devotion, and a reflection of the soul's deepest longings. Whether through the structured odes of qasidas, the mystical verses of Sufi poetry, or the heartfelt expressions of ghazals, literature has played an integral role in shaping spiritual consciousness across generations. During Ramadan, this connection becomes even more profound, as poetry enriches dhikr, enhances personal reflection, and fosters a deeper connection with Allah. The fusion of literature, culture, and spirituality has made these poetic forms accessible and meaningful to the masses, transforming them into a living tradition rather than a relic of the past.

As Ramadan continues to be a time of self-reflection and divine closeness, poetry remains a timeless companion on this journey. It speaks to the struggles of the heart, the beauty of faith, and the boundless mercy of Allah. Whether sung in the quiet of pre-dawn hours, recited in the solitude of reflection, or shared in the company of fellow believers, devotional poetry continues to illuminate souls, reminding us that faith is not just practised; it is felt, expressed, and lived.

Mahmuda Emdad is a women and gender studies major with an endless interest in feminist writings, historical fiction, and pretty much everything else, all while questioning the world in the process. Feel free to reach out at mahmudaemdad123@gmail.com.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments