‘Pakhider Bidhanshabha’: A mesmerising theatrical odyssey

On the evening of February 10 the curtain fell for the last time on a performance that, over the preceding days, had cast an enchanting spell upon its audience. From February 7 onward, the master's students of Theatre and Performance Studies at the University of Dhaka summoned the winds of an ancient parable, carrying their audience through the mystical landscapes of Farid ud-Din Attar's Manṭiq-uṭ-Ṭayr (1177)–Pakhider Bidhanshabha in Bangla, The Conference of the Birds in English. What unfurled was not mere theater but an invocation—a dreamscape woven with movement, music, and metaphor—an invitation to traverse the valleys of the soul.

Attar's 12th century Sufi allegory, masterfully adapted by writer and playwright Dr Shahman Moishan and directed by Dr Ahmedul Kabir, follows a gathering of birds who, led by the wise hoopoe, embark on a perilous journey to find their king, the Simurgh. They must cross seven valleys, each demanding the surrender of human frailty—Certainty, Love, Understanding, Detachment, Unity, Bewilderment, and finally, Self-Realisation. Many falter, overcome by fear or pride, but the few who reach the end discover an astonishing truth: the Simurgh is not a distant ruler but a reflection of themselves.

At its heart, Pakhider Bidhanshabha explores spiritual enlightenment—a voyage through doubt, suffering, and transcendence. But this adaptation has breathed new life into Attar's verses, injecting a visceral contemporary urgency into the age-old search for truth.

The hoopoe played with commanding presence, was no longer just a mystical guide but a figure reminiscent of political dissidents, spiritual visionaries, and lone voices of conscience in turbulent times. The birds, reflecting their human counterparts, wrestled with desires, distractions, and self-imposed limitations—echoing the struggles of modern existence, where the pursuit of meaning is often stifled by materialism and fear.

This performance was not a relic of ancient Sufi thought but a living, breathing dialogue with today's world, asking: What illusions hold us back? How do we break free?

Pakhider Bidhanshabha exemplifies Brechtian techniques through its deliberate use of alienation to critique societal systems and provoke reflection. The performance dismantles traditional theatrical conventions by presenting its characters as symbolic representations of institutional power and corruption. These allegorical figures embody abstract ideas rather than individual personalities, compelling the audience to critically assess the broader societal dynamics at play.

The episodic structure of the play prevents emotional immersion, a hallmark of Brechtian theater. Each scene functions as a self-contained critique of a specific aspect of governance, such as manipulation, ethical dilemmas, or societal decay. This fragmented storytelling denies the audience the comfort of narrative continuity, forcing them to remain analytical throughout the performance.

The play's portrayal of philosophical debates, such as doubt and uncertainty, further distances the audience from passive engagement. Instead of inviting empathy, it challenges viewers to examine the contradictions inherent in institutional systems. For instance, moments of irony and absurdity in the dialogue and actions expose the hypocrisy and ineffectiveness of those in power, amplifying the critical distance between the audience and the narrative.

To stage Pakhider Bidhanshabha is to dance on a tightrope—veer too far into abstraction, and you risk alienating your audience; lean too heavily on exposition, and you lose the mysticism. This production, however, achieved a delicate equilibrium, balancing poetry with raw theatricality.

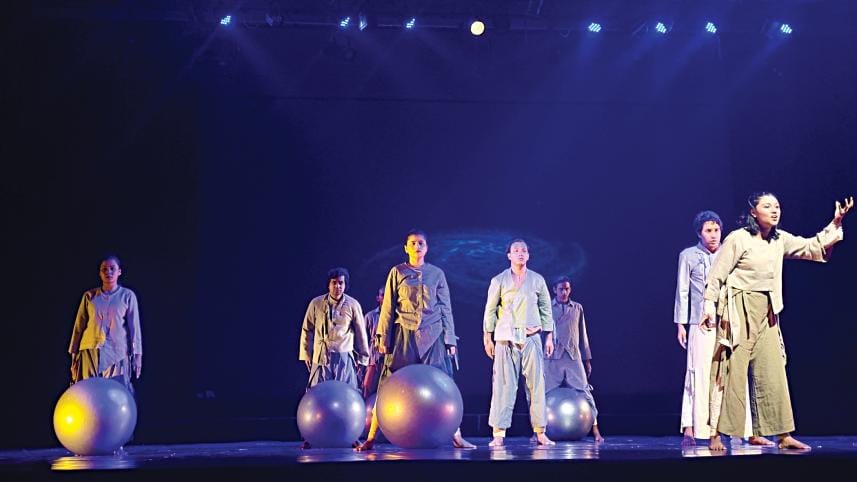

The ensemble embodied the restlessness of the human condition, shifting between hypnotic unity and desperate individuality. Choreographed sequences fused elements of classical South Asian movement with experimental physical theater, making the birds' journey feel both celestial and achingly human.

The use of light and shadow was particularly striking. At moments, the stage was drenched in golden hues, evoking the promise of enlightenment; at others, fragmented beams of light created the illusion of imprisonment—birds caged by their own fears. The crescendo of live music, interwoven with haunting vocal chants, transported the audience into a trance, mirroring the Sufi tradition of sama—a musical path to divine ecstasy. That elusive Sufi dance deepened the mystique, blurring the line between the corporeal and the divine.

However, the narrative structure was not without its flaws. There were moments when the poetic dialogue, though beautiful, risked becoming esoteric. Some of the more intricate Sufi metaphors might have benefited from visual storytelling rather than linguistic elaboration. That said, these minor lapses did not dull the brilliance of the overall execution.

What set this performance apart was its bold artistic choices—a fusion of classical and avant-garde, mysticism and modernity. Director Kabir orchestrated a theatrical language that was at once ancient and immediate, refusing to be confined by time or tradition.

The costume design, led by Mohsina Akhter, was a symphony of textures—earthy tones for those tethered by worldly desires, while those who reached transcendence were enveloped in ethereal whites, bathed in the illusive shades of blue lights, and reflected in a stage of mirrors. Meanwhile, the set was minimal yet evocative—a shifting landscape of fabric, mirrors, and shadows that transformed seamlessly into deserts, mountains, and celestial realms.

Perhaps the most radical artistic decision was the treatment of Simurgh's revelation. Instead of a singular grand moment, the climax was fractured, splintering across multiple perspectives—some birds saw nothing, some saw themselves, and some glimpsed a cosmic void. It was a masterstroke that left the audience grappling with their own interpretations, refusing easy resolutions.

As the final echoes of the performance faded into the night, the audience sat, momentarily suspended—caught between the weight of the questions it had posed and the personal reckoning it demanded. The Conference of the Birds was never meant to be a passive experience, and this adaptation ensured it wasn't.

In a world teeming with distractions, where certainty is mistaken for truth and doubt for weakness, this production stood as an act of defiance—an invitation to embrace the unknown, to embark on a journey within. It did not offer answers, only a mirror, leaving the audience to confront the reflection they found there.

And that, perhaps, is the highest form of theater.

Naseef Faruque Amin is a writer, screenwriter, and creative professional.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments