The books that went to war

The books authored and published during a war always have an archival quality; they capture the time in its crudest form. They are a seamless blend of all the possibilities of the time and the event. Hope and despair. Confidence and Confusion. Spontaneity and determinism.

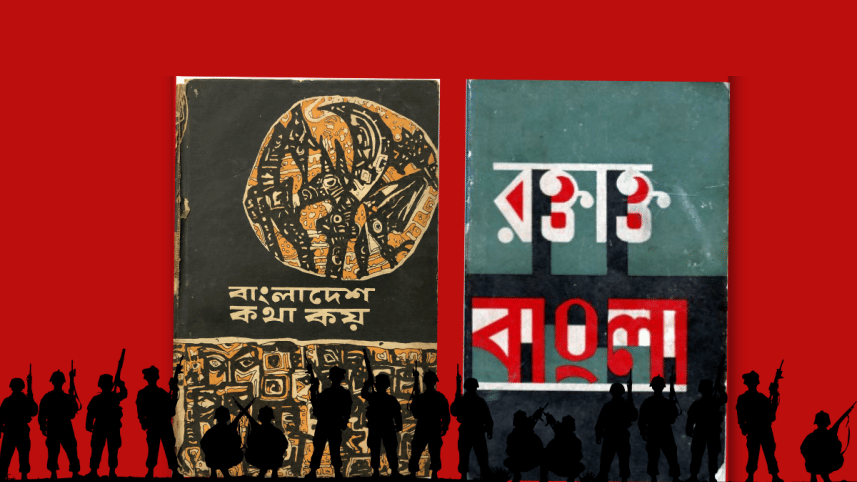

During the Bangladesh Liberation War of 1971, several books were published of which two deserve special mention: Roktakto Bangla and Bangladesh Kotha Koy. The books were published by Swadhin Bangla Sahitya Parishad Muktadhara, founded under the leadership of Chittaranjan Saha, who would find new fame in 1972 for his pioneering role in starting the Ekushey Boi Mela.

Before going into the details of the two books, a brief account of Saha may not be irrelevant. Although born into a merchandiser family from Noakhali, Chittaranjan Saha chose the book business. His bookshop burnt down early into his venture, but he did not let it hinder his business or his passion. He began from scratch once again, and started publishing on his own. This time he found success and expanded his business further. He moved from Chaumohani to Dhaka in 1956, and set up the office for his publication house, Punthighar Prokashoni, in Old Dhaka.

When the Liberation War broke out in 1971, the West Pakistani army burnt down the office, showroom, and storeroom of Prokashoni Punthighar. During this most tumultuous time, Saha sought refuge in Kolkata—once again, he didn't lose hope. He invested himself fully in the war effort. His choice of weaponry were books.

Saha started contacting the Bangladeshi intellectuals who had similarly taken shelter in Kolkata and brought them together to publish Roktakta Bangla ("Blood-stained Bangladesh")—this would be the beginning of his new publishing house, Muktodhara, which went on to publish 23 books during the Liberation War.

Released in August of 1971, Roktakta Bangla, was a collection of articles compiled and edited by the late great National Professor Anisuzzaman. The book was dedicated to the memory of the martyrs who lost their lives to the genocide perpetrated by the Pakistani junta and those who sacrificed their lives in the resistance fight.

Professor Azizur Rahman Mallick, Vice-Chancellor of Chittagong University, wrote in the preface: "Though Bangladesh is soaked in blood today the struggle for independence is fierce. Bangalis are fighting for freedom, for justice, for the values always dear to human beings. They are fighting with firm conviction, they are fighting for victory".

The collection contains articles on the political, economical, and sociological background of the struggle for freedom. They provide a detailed account of the colonial aggression carried out by successive West Pakistani regimes against the eastern part of the country. The authors place the Liberation War in the context of a 23-year long struggle against Pakistani colonialism. The article titled "Pakistaner Shikshaniti" ("Education Policy of Pakistan") authored by Ahmed Sofa, for example, critically analyses the education policies adopted during various regimes in Pakistan and delineates how the West Pakistani rules carried out a persistent attack on the education system of East Pakistan to control and subjugate Bangalis.

Three months from the release of this history-making collection, another book, published in November 1971, would contain stories authored by leading literary figures of the new-born Bangladesh, like Shawkat Osman, Satyen Sen, Zahir Raihan, and Nirmalendu Goon. The anthology would be called, fittingly, Bangladesh Kotha Koy.

The authors in this collection speak of the dreadful experiences of the genocide and the shared traumas of betrayal. The stories themselves, however, never concede to hopelessness. They exude the spirit of unwavering patriotism—burning still, if not brighter, after the cold airs of death that had just blown through this country's borders.

Noted filmmaker Zahir Raihan authored a short story titled, "Shomoyer Proyojone" ("Demand of the Time") for the collection. In it, the lead character, a young freedom fighter, searches his soul to find why exactly he had joined the war. He recounts several responses from his fellow fighters. Some said they took up arms to take revenge, some said they were fighting against the injustice inflicted on Bangalis by West Pakistanis, some said they were obeying the order of Sheikh Mujibur Rahman. But those answers were not his own, and they failed to satisfy. The question persists in him and, by the end, grows in stature; he wonders soon why so many people were so readily sacrificing their lives, so willing to part with the most sacred of things. The protagonist finds neither answer nor solace. He resigns simply to the idea that "maybe we were just responding to the demand of the time".

With the benefit of hindsight we may differ with some of the analyses present in the books discussed above, but what is undeniable is that the works show the commitment of the Bangali intellectuals who responded to the demands of the time with their utmost sincerity, patriotism, and passion for freedom. These works can be sources of inspiration for present-day intellectuals—a reminder of how to speak truth to power, even if to an overlording dictator.

Shamsuddoza Sajen is a journalist and researcher. He can be contacted at sajen1986@gmail.com

For more book-related content, follow Daily Star Books on Facebook, Instagram, Twitter, and LinkedIn.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments