The journalists sued by the Thai navy

A court in the southern Thai island of Phuket has acquitted two journalists of defaming the navy and breaching the Computer Crimes Act.

Chutima Sidasathian and Australian Alan Morison, from news site Phuketwan, faced possible jail time for a line in a 2013 article on human trafficking.

The excerpt, from Reuters news agency, quoted an unnamed smuggler saying Thai naval forces made money from turning a blind eye to trafficking.

Reuters does not face any charges.

Reuters and Phuketwan were the first to examine reports of Thai involvement in the trafficking of Rohingya from Myanmar and Bangladesh.

Ahead of the verdict Alan Morison and Chutima Sidasathian spoke to the BBC's Jonathan Head about their battle to expose the misery behind the trade.

It was the Thai Navy which first alerted Alan Morison and Chutima Sidasathian to the story for which they were then sued - by the Thai Navy.

They had faced a possible seven years in prison for a short paragraph they included in an article on trafficking and Rohingyas in 2013.

Back in November 2008, Alan and Chutima had been running their online news site Phuketwan for nearly a year.

Alan, a former editor for the Melbourne Age who had moved to Phuket from Australia in 2002, says they wanted Phuketwan to go beyond the typical agenda of existing news outlets of colourful lifestyle articles promoting the island's tourism industry, to provide "an accurate account in words and photographs of Phuket and its people".

With hundreds of thousands of foreigners visiting every year, there was never any shortage of local stories to cover, often involving tourists in trouble, accidents, or shady law-enforcement. But the story they broke in late 2008 was on a different scale altogether.

Chutima had good relationships with a number of Thai navy officers, who worked on the large naval base on the island. From them she heard about the large number of Rohingya Muslims from Myanmar arriving on Thailand's Andaman coast, north of Phuket.

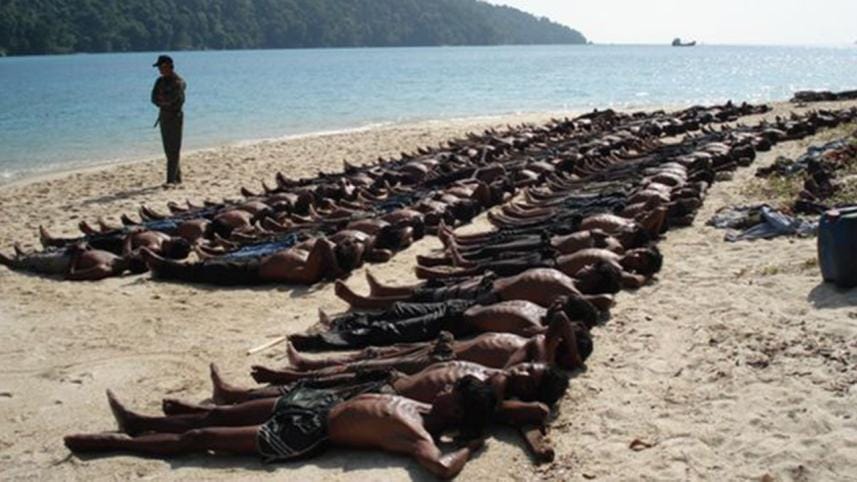

Officers mentioned that there had been a change of policy. Instead of being detained and looked after, they were being held on offshore islands. The navy did not want to take her there. Instead they gave her photographs, showing dozens of emaciated-looking men being made to lie down on a beach.

Further investigation revealed something worse; that Thai forces were towing boats packed with Rohingyas back out to sea, and setting them adrift, sometimes without engines. Unknown numbers died before they washed ashore.

Alan and Chutima have kept on covering the Rohingya issue, especially the networks of traffickers that have developed in Thailand to exploit the migrants. They say they were nervous at times, writing articles critical of powerful Thai institutions like the police, immigration department and military. For years, though, nothing happened, and they say they enjoyed cordial relations with most of the officials they encountered.

That changed in December 2013, when a police officer came to their office and told them they were being charged with criminal defamation and violating the 2007 Computer Crimes Act. The two charges carry a maximum penalty of seven years in prison.

"I was very surprised", says Chutima. "I thought at first it must be the police or immigration, who we had often criticised. But it was a navy officer." Both journalists say they have often given positive coverage of the navy's role in the region, and even on the Rohingya issue.

It turned out the navy was citing a 41-word paragraph in an article published six months earlier in Phuketwan. This was actually a quote by an unnamed smuggler used in an investigative feature by the Reuters news agency, which referred to the involvement of "Thai naval forces" in human trafficking. The Reuters journalists went on to win a Pulitzer prize for that and other reports on the Rohingyas.

"It was a shock," says Alan. "I felt it was an issue that could have been settled by a phone call." Phuketwan offered the navy space to put its own views. The navy declined.

The decision by the Thai navy to file such heavy charges against the journalists has been widely condemned by governments and human rights organisations. The navy has insisted it must proceed, because it believes its reputation has been damaged. A number of attempts, some backed by the Thai government, have been made to settle the issue out of court.

First action against traffickers

But the case ploughed on, despite the extensive media coverage this year of the trafficking business in Thailand, the terrible human cost of that business, and the clear involvement of Thai officials, military, police and civilian.

For the first time the Thai government has this year taken concerted action against traffickers, after the discovery of mass graves in jungle camps where Rohingyas and other migrants were held for ransom.

One of the country's powerful army officers, Gen Manas Kongpan, who ran the special operations command ISOC in the area during the "push-back" policy of 2009, has been arrested and indicted. Military and police officers have told the BBC that the navy is involved in trafficking, although this has been impossible to prove.

But the first big court case in Thailand related to the Rohingya boat people crisis has been the one against two independent journalists, who have done more than most to highlight the trafficking and smuggling problem.

"The reputation, their image, has been destroyed because they started suing the media," says Chutima. "They damaged their image by themselves, not because of the media, not because of me."

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments