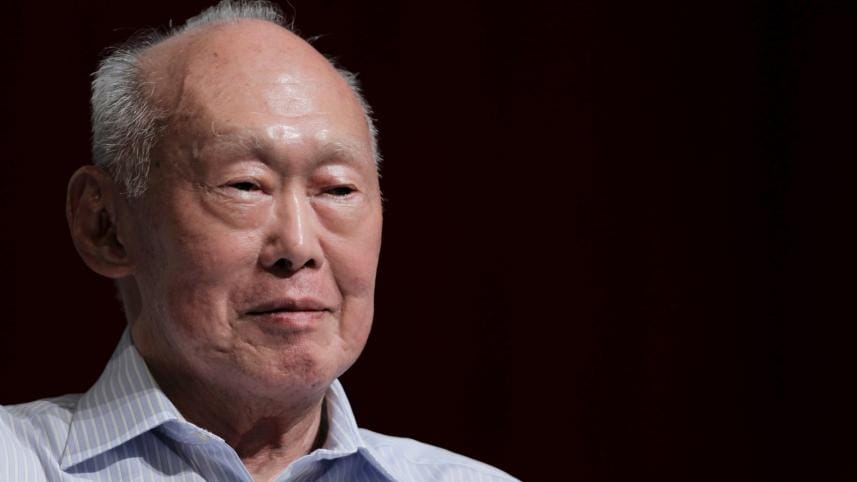

Singapore founding father Lee Kuan Yew dies

Singapore's founding father, Lee Kuan Yew, has died, leaving behind the unlikely nation that he and his colleagues fostered and built over five decades as his lasting legacy.

Lee, who would have turned 92 this September, died at the Singapore General Hospital where he had been warded for severe pneumonia since Feb 5.

A statement from the Prime Minister's Office said: "The Prime Minister is deeply grieved to announce the passing of Lee Kuan Yew, the founding Prime Minister of Singapore. Lee passed away peacefully at the Singapore General Hospital today at 3.18 am. He was 91."

[twitter]

PM Lee is deeply grieved to announce the passing of Mr Lee Kuan Yew, founding Prime Minister of Singapore. pic.twitter.com/wr0te0xMvK

— Lee Hsien Loong (@leehsienloong) March 22, 2015[/twitter]

Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong has declared a seven-day period of national mourning. As a mark of respect, the state flags on all government buildings will be flown at half-mast for the mourning period, which starts on Monday, March 23, and ends on Sunday, March 29.

A private family wake will be held on Monday, March 23, and Tuesday, March 24, at Sri Temasek.

Lee's body will lie in state at Parliament House from Wednesday, March 25, to Saturday, March 28, for the public to pay their last respects. They can do so from 10:00am to 8:00pm daily during that time.

[twitter]

Condolence boards are available at Istana's Main Gate from 23 to 29 Mar, for tributes to the late Mr Lee Kuan Yew. pic.twitter.com/8Ecpo1hmEu

— Lee Hsien Loong (@leehsienloong) March 23, 2015[/twitter]

A state funeral service for Lee will be held at 2:00pm on Sunday, March 29, at the National University of Singapore's University Cultural Centre.

The service will be attended by the late Lee's family, friends and staff, President Tony Tan Keng Yam, Cabinet Ministers, Members of Parliament, and Lee's fellow founding members of the ruling People's Action Party.

Senior civil servants, grassroots leaders and Singaporeans from all walks of life will also be attending the service, which will be followed by a private cremation at Mandai Crematorium.

Condolence books and cards will be available in front of the Istana main gate from Monday to Sunday, for those who wish to pen their tributes to the late Lee. Condolence books will also be opened at all overseas missions for overseas Singaporeans and friends.

Lee leaves behind his sons, Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong, 63, and Lee Hsien Yang, 57, daughter Dr Lee Wei Ling, 60, daughters-in-law Ho Ching, 61, and Lee Suet-Fern, 56, seven grandchildren and two siblings. His wife, Madam Kwa Geok Choo, died in 2010, at the age of 89.

The elder Lee is widely regarded as the man most instrumental in shaping Singapore, from the time he and his People's Action Party colleagues pushed for self-government in the 1950s, to their quest for merger with Malaysia in the early 1960s, and their efforts to secure the country's survival after independence was thrust on it on Aug 9,1965.

He famously wept on that occasion, which he immortalised as "a moment of anguish", not only as he had believed deeply in a unified Malaysia as a multi-racial society, but also as he must have sensed the enormity of the task for this fledgling state to make a living in an inhospitable world.

He would lead a pioneer generation of Singaporeans to overcome a series of daunting challenges, from rehousing squatters in affordable public housing, rebuilding the economy after the sudden pull-out of British forces and the oil shocks of the 1970s, and a major economic recession in the mid 1980s. Through it all, Lee would exhort his people to take heart and "never fear" as they looked forward to a better life.

"This country belongs to all of us. We made this country from nothing, from mud-flats... Over 100 years ago, this was a mud-flat, swamp. Today, this is a modern city. Ten years from now, this will be a metropolis. Never fear!" he thundered at a grassroots event in Sembawang in September 1965.

He delivered on this promise, earning the trust of generations of voters. This would see his party returned to office repeatedly over three decades. By the time he stepped down in 1990, he had served 31 years as PM, from 1959 to 1990. At the age of 67, he chose to hand over the premiership to Goh Chok Tong, and took on the role of senior minister, serving as guide and mentor in the Cabinet.

Noting this unusual willingness to relinquish power, Time magazine wrote in 1991: "What really sets this complex man apart from Asia's other nation-builders is what he didn't do: he did not become corrupt, and he did not stay in power too long. Mao, Suharto, Marcos and Ne Win left their countries on the verge of ruin with no obvious successor. Lee left Singapore with a per capita GDP of $14,000, his reputation gilt-edged and an entire tier of second-generation leaders to take over when he stepped down in 1990.

"Lee now basks in the wisdom of seniority, a latter-day Doge whose views continue to be sought by statesmen and commentators who travel from all over the world to pay court to him in Singapore."

Later, when PM Lee took charge in 2004, the elder Lee became Minister Mentor, taking a further step back from being a prime mover in government and spending his time pondering the longer term challenges facing Singapore.

His decades in office were not uncontroversial. Having survived life-and-death battles with the communists and communalists in Singapore's tumultuous early years, he made plain that he was not averse to wielding the proverbial big stick, declaring his readiness to confront political foes with "knuckle dusters". He insisted that he would not rule by opinion polls, rejecting the idea that popular government entailed a need to be popular through his term, believing that voters would come round when they eventually saw the results of policies he had pushed through.

As he said in an interview for the book, Lee Kuan Yew: The Man And His Ideas: "I'm very determined. If I decide that something is worth doing, then I'll put my heart and soul to it. The whole ground can be against me, but if I know it is right, I'll do it. That's the business of a leader."

He was both a visionary and a radical thinker. He was instrumental in a host of major policies that have shaped almost every aspect of Singaporeans' lives, from promoting public housing, home ownership and later estate upgrading, to adopting English as a common language for the disparate races in Singapore society which would also help it plug into the global economy, to his lifelong passion for planting trees and keeping the island "clean and green" long before such environmental-consciousness became fashionable.

In 2005, after decades of being stoutly opposed to gambling, he surprised many when he indicated that he had changed his position and backed the introduction of two integrated resorts with casinos. His reasoning was direct and simple: it was necessary, if Singapore was to stay relevant in a changing world. As always, his ultimate arbiter was "what works", and furthered Singapore's interests.

As former President S R Nathan, who worked closely with Lee in several roles in government over the years, recalled in an interview: "His first and only priority was the good of Singapore and its people... his mind never stopped working as he mulled over the issues, big and small, that confronted Singapore.

"If he travelled anywhere, he was always asking if something he saw could be applied in Singapore. He would grill anyone he met for ideas that could be useful... he was totally preoccupied with our survival and prosperity."

In one memorable National Day Rally speech in 1988, Lee declared that Singapore was his life's work, adding half in jest, that "even from my sick bed, even if you are going to lower me into the grave and I feel something is going wrong, I will get up" to alert Singaporeans to any perils he saw ahead.

That he did to the very end, urging Singaporeans to have more babies and be more open to and welcoming of immigrants in order to deal with the rapid ageing of the population, which became a recurrent theme of many of his speeches in his later years.

He carried on with his public duties after retirement, and even after the loss of his beloved wife of 63 years, Madam Kwa, whom he married secretly when they were undergraduates in Cambridge in 1947. He mourned her deeply, but mostly in private, including gazing at pictures of happy times with her, when he sat alone at their dinner table in 38 Oxley Road, where he and s Lee had shared years of companionship.

His two-part memoirs, The Singapore Story, which became a bestseller in several languages, noted how he and his colleagues believed that Malaysian leaders expected that an independent Singapore would fail and be forced to seek readmission to the Federation - this time on Malaysia's terms. Lee had other plans, and declared: "No, not if I could help it. People in Singapore were in no mood to crawl back after what they had been through."

"The people shared our feelings and were prepared to do whatever was needed to make an independent Singapore work. I did not know I was to spend the rest of my life getting Singapore not just to work but to prosper and flourish."

Asked once if he would have done things differently if he could live life over, he replied with characteristic candour: "All I can say is, I did my best. This was the job I undertook, I did my best, and I could not have done more in the circumstances. What people think of it, I have to leave to them. It is of no great consequence.

"What is of consequence is I did my best."

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments