Challenging the essence of Iranian regime

More than three weeks of protests have rocked Iran after a young woman died after being detained by the country's so-called morality police.

The 22-year-old Mahsa Amini had travelled to Tehran with family from the northwestern Kurdistan province when she was detained for what the police deemed to be "immodest clothing" on September 13.

Authorities claimed that she had a heart attack while staying in a "guidance centre" – a type of re-education centre where women are taught how to follow Iran's rules on female clothing. Her family has alleged that officers beat her head with a baton and banged her head against one of their vehicles.

She was declared dead on September 16 by state television after having spent three days in a coma. Iranians took to the streets across the country, calling for justice for Amini, angry at the authorities and morality police, who they blame for her death.

Iran Human Rights, a Norway-based group, has said at least 133 people have been killed by security forces so far. State media have reported that more than 40 people have died, including security personnel. Scores, including a number of journalists, students, lawyers and activists, have been arrested.

After remaining silent for three weeks, Iran's supreme leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei on Monday blamed the US, Israel and "some traitorous Iranians abroad" for the protests. He urged security forces to be ready for more.

The West has been vocal since the protests erupted. The US has already imposed sanctions on Iran's morality police, and President Joe Biden said that this week his administration would "impose further costs" on those perpetrating violence against peaceful protesters. A number of Western countries summoned Iranian envoys to lodge protest against the crackdown.

PROTESTS FLARE AT A DELICATE TIME

The protests come at a delicate time for the regime. Anger has been simmering in Iran as years of US-led sanctions have hobbled its economy. Widespread corruption and economic mismanagement also played a big part. And Tehran's hope of improving the situation seems unlikely as talks on restoring the nuclear accord seems to have collapsed after glimpses of progress.

The protests also come at a time when the world is going through a major geopolitical shift. Iran has been a vocal supporter of a new emerging bloc led by China-Russia, which is trying to pose a challenge to West's dominance.

Now, despite the harsh crackdown, the demonstrations have become widespread, with demands broadening to reflect ordinary Iranians' anger over their living conditions.

MANDATORY HIJAB AND PROTESTS

Amini's case has touched a raw nerve and unleashed years of pent up anger over the mandatory hijab.

In an unprecedented manner, Iranian women are challenging the country's Islamic dress code, waving and burning their veils. Some have publicly cut their hair as furious crowds called for the fall of Ayatollah Ali Khamenei.

Under a law adopted in 1983, four years after Iran's Islamic revolution, all women, regardless of faith or nationality, must conceal their hair with a headscarf in public and wear loose fitting trousers under their coats. Violators face public rebuke, fines or arrest.

But decades after the revolution, clerical rulers still struggle to enforce the law, with many women of all ages and backgrounds wearing tight-fitting, thigh-length coats and brightly coloured scarves pushed back to expose plenty of hair.

While that defiance is common, the nationwide protests have raised the stakes as Iranian women call for more freedoms.

In the first few days, Iranian media criticized the so called morality police. The day after her funeral, nearly all Iranian press dedicated their front pages to her story.

Reformist political parties, and even influential clerics called on the government to listen to the people.

However, that reformist tone has changed notably as protests spread. Presumably, under strict pressure from the regime, the media has projected the protests as an assault against religious values.

Waves of the hijab protests have hit the clerical establishment in the past years. In 2014, rights activist Masih Alinejad started a Facebook campaign "My Stealthy Freedom", where she shared pictures of unveiled Iranian women sent to her. Her movement was followed in 2017 by a hashtag campaign encouraging women to wear white scarves on Wednesdays to protest laws requiring hijab.

And in the months and years that followed, new photos and videos and stories of women removing their hijab or resisting the morality police flooded social media.

Veiling in Muslim societies has always been heavily contingent on geographic, socioeconomic, and historical context, and in contemporary Iran, the issue has long been politicised. In 1936, the first Pahlavi shah issued a decree that prohibited veiling in a bid to modernise his country.

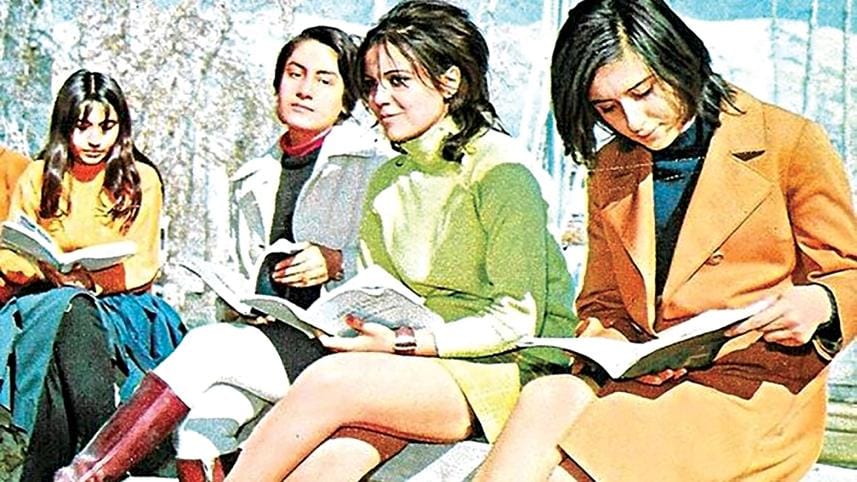

The edict lapsed a few years later, when the shah was forced into exile and his young son took the helm. Mohammad Reza Pahlavi doubled down on his father's secular, pro-Western orientation, and in the 1970s, as anti-government activism gained momentum, many women consciously adopted headscarves or all-enveloping chadors as tangible rejections of the monarchy.

Still, even from the start of the post-revolutionary era, the efforts by the state to impose and enforce hijab provoked intense resistance. In the weeks after the monarchy was toppled, hints of a crackdown on women's dress prompted some of the first protests of the post-revolutionary era, drawing thousands of women to the streets in March 1979 to warn that the imposition of headscarves by the new leadership threatened their rights.

But the activism against hijab was also controversial from the start.

In a country where women require a man's approval for travel and marriage, where laws surrounding divorce and custody and inheritance favour men, and where female labour force participation is among the lowest in the world despite high educational attainments, it's understandable that some downplay the significance of hijab as secondary to other matters such as political or gender equality rights.

But the issue that most of us fail to understand is, for Iranian women, this whole hijab decision is imposed on them. For them, banning the hijab was imposed, so was the imposition of mandatory hijab. For them, it's not about the clothes, it's about the coercion.

According to one independent study from 2020, 72 percent of Iranians are against mandatory hijab-wearing. By contrast, only 15 percent support it.

QUESTIONING THE ESSENCE OF REGIME

For the ruling clergy, the anti-hijab campaigns strike at the heart of the ideology that validates arbitrary and unaccountable power in Iran. To question hijab is to question the essence of the Islamic Republic, and to express those questions in a way that demonstrates impatience with the perennial assurances of "peaceful reform" confounds the deeply-held political narratives of many, both inside and outside Iran.

Among the regime's senior leadership, mandatory hijab-wearing has become a nonnegotiable litmus test for anyone who professes loyalty to the Islamic Republic. Once mandatory hijab-wearing is challenged and potentially revoked, the thinking goes, opponents will simply move on to contest the regime's other cherished policies.

Whether this ongoing protest can generate durable policy change, or even regime change, is hardly certain. Tehran has massive repressive capacity at its disposal that extends well into the online space.

Iran was rocked by unrest in 2017 and 2018. In 2019, Iran said 200,000 people took part in what may have been the biggest anti-government demonstration in the 43-year history of the Islamic Republic. Reuters reported 1,500 were killed by security forces.

All these protests were brutally suppressed.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments