Taxing sugary drinks and promoting healthy food are the way to go

"Do you have it?" ("Apnar ki achhey?")

Anyone who has recently started exercising in a public space has probably heard this question, or seen people ask it to their acquaintances. There is no need to specify the "it"—everyone knows that a diagnosis of diabetes is the most common spur for people to begin exercising.

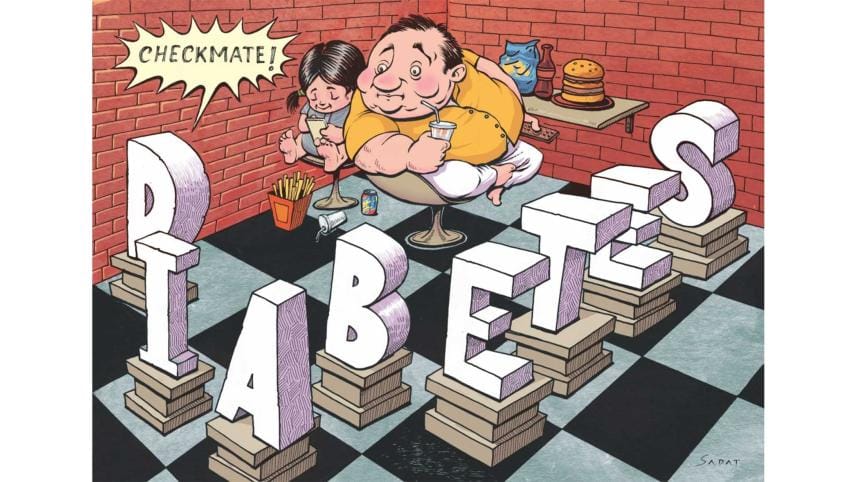

Which is odd, given that most people would agree that prevention is vastly preferable to suffering from a lifelong, chronic disease. And how do we prevent diabetes? The advice is pretty simple and in line with prevention for other non-communicable diseases such as heart disease, cancer and strokes: maintain a healthy weight, exercise, eat healthy (avoid processed foods and excessive white rice), and drink water, but avoid sugary or artificially sweetened drinks. The problem with the prevention strategy is that nobody makes money promoting it. There are various health organisations who publicise diabetes prevention and healthy lifestyle messages, but they are overwhelmed by the advertisements for just the products that contribute to diabetes, such as fast food, sodas, and artificial juices.

As for exercise, who has time for that? The idea that exercise means going to a gym discourages many people from getting their needed daily physical activity. And for all too many people, the incentive to start exercising depends on the diagnosis, not on the desire to prevent diabetes.

The easiest way to get your needed physical activity is to incorporate it into your daily routine. That means walking or cycling to destinations, such as schools, universities, workplaces, and shops. If your workplace is not that far away, it can be faster to reach it by foot than by bus; if it is far, cycling is probably much faster than daily commutes in a car on congested streets—so, walking or cycling can also save you time. Of course, it would help if we rewarded, rather than punished, those on foot and on bicycles by making the environment for active transport attractive, rather than atrocious. A happy by-product of this lifestyle would be decreased carbon emission into the atmosphere by virtue of cutting back the use of motorised vehicles.

It would be easier to eat a healthy diet if there were fewer ads for unhealthy foods and more information available about healthy eating. Limits or bans on advertisements for unhealthy foods are one option. There could also be a surcharge on sugary beverages, raising the price and thus reducing their use. Better yet, that surcharge could be used to fund a health promotion foundation that would engage in a number of activities to keep people healthier—such as supporting research on effective approaches to reducing diabetes in high-risk populations; communication efforts to encourage people to live more healthfully; collaboration across different agencies, including those working on public health, transport and the environment; and advocacy for policies to promote healthy foods and enable active transport by prioritising walking and cycling over driving cars.

There are several excellent models for the work a health promotion foundation could do. The most famous ones are VicHealth in Australia and ThaiHealth in Thailand. They and other health promotion foundations help keep people healthier, and thus reduce the burden on hospitals, doctors, nurses, and the health authorities. While health promotion foundations are usually funded by a surcharge on tobacco and alcohol, many countries have implemented a sugar-sweetened beverage tax, which has resulted in significant decreases in the consumption of sugary drinks. Better yet, some places such as Berkeley in California, US use the revenue to support healthy eating; in the case of Berkeley, the tax goes, among other things, to fund students to learn about gardening and healthy cooking from the youngest ages through university.

Today, World Diabetes Day, is a good time to consider positive solutions to the devastation wreaked by diabetes in Bangladesh, which had more than eight million diabetic patients as of 2020, according to the International Diabetes Federation. There are many excellent reasons to put a surcharge on sugary drinks and use it to create an organisation devoted to keeping people healthier. There are also many excellent reasons to help people incorporate healthy practices into their lifestyle, so that when we see each other out walking, we no longer assume that it is because of having "it."

Debra Efroymson is regional director of HealthBridge Foundation of Canada, and co-author of "Broadening the Focus from Tobacco Control to NCD Prevention: Enabling Environments for Better Health."

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments