Student protests: A new life form is possible

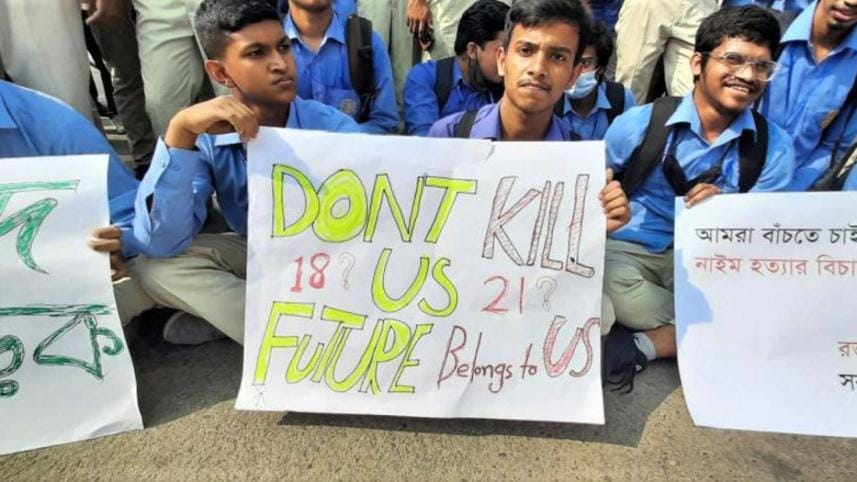

The tragic road accident and the unfortunate death of Nayeem Hasan, a student of Notre Dame College, on November 24, sparked protests as fellow students took to the streets of Dhaka yet again. They demanded a speedy trial of the accused, compensation for the family, strict traffic laws, etc.

Protests for road safety is not new. Regrettably, the law formulated in 2018 following even larger student protests after the death of two students in a similar road accident is yet to be fully enacted. Nonetheless, the unity shown by the students in the past few years for restructuring the quotas in government jobs, eliminating imposed VAT on tuition fees, enacting new traffic laws, etc., is admirable. All these protests reflect similar aspirations for equality and justice, and more importantly, show the power of unity.

Students break the divide between the rulers and the governed during these protests and make the fallacies of certain rules and laws visible. For example, since the start of the latest demonstrations, they checked driver's licences on the roads. On the second day of the protests, the driver of a police bus could not show his driver's licence and instead arrogantly said, "his uniform is the licence, the arms of the police are the license"—according to reports from the protesting students. Usually, it is true, people in authority can and do make such claims. But during mass protests, at least momentarily, the power structure is reversed. The students did not let the bus leave, higher officials had to come to the scene, and the bus driver publicly apologised before being allowed to go on with his duties.

In another incident on the same day, the mayor of Dhaka South City Corporation had to come out of his office to pledge before the students that he would take steps against those people involved in garbage truck management irregularities. The mayor also announced that he wanted the execution of the driver of the vehicle that killed the student. This was contrary to the usual. People wait long hours to meet the office-bearers in government offices, but facing a protest, the mayor came out and made commitments before the students. This was possible only because the horizontal cooperation among the students without recognised leadership—an important feature of the recent student protests—left no options. Typically, authorities want to talk with the representatives during a demonstration, but having no specific leader makes it difficult for the authorities to negotiate. So, rather than inviting the representative to an office, the office bearers are forced to come to the protesters. Again, we see the power of equality and unity—a welcome change in the country's political culture.

The student protests have shown that it is possible to collectively challenge state authority, which sociologist Emile Durkheim identified as effervescence: A time of great collective shock resulting in frequent and active social interaction. Student protests have become routine in past years—possibly leading to a revolutionary or creative epoch. Fundamental elements of these protests are a festive atmosphere, auto-generation, networks among protesters created and sustained through social media, a takeover of infrastructure (e.g. roads and blockade of the mayor's office), and gradual expansion. Following the students' demonstration from Notre Dame College, others gathered in various parts of the city. The organisational character of the protests exhibits a new form of organising discontent. Thus, we can identify more significant implications of these protests beyond the reductive label of "student protests". The student uprisings, in Alain Badiou's words, can womb an "[idea] capable of challenging the corrupt, lifeless version of 'democracy', which has become the banner of the legionaries of Capital". The frequency of student protests indicates the possibility of forming a more egalitarian society.

But how should we go about forming a new society? Should we aim for new laws, for example, for governing traffic in the country? This demand for more formalised laws—seeking an enhanced humane condition or equality—may contrarily curb the potentials of cooperation and agency. The imposition of more regulatory procedures usually leads to authoritarianism and power concentration. If examined critically, the solution that the people in power also propose in the face of mass protests is about formulating new laws for governance. Recently, fines for violation of traffic rules were hiked, and many people believe it will make drivers follow traffic rules diligently. Conversely, some sceptics also predicted that it would only increase bribery to avoid fines and legal action.

The fascination with creating new laws arises from the assumption that we will be more humane once an authority enforces regulations. Contrarily, it keeps us from transforming the authoritarian socio-political system for a better democracy or a more equal and just society. Remarkably, the student protests repeatedly show, it is possible to maintain equality and justice by being anarchists—uniting and carrying our everyday affairs spontaneously. Many would relate anarchism with violence, disorder and destruction. But philosophically, as David Graeber has argued, anarchism proposes that human beings are capable of reasoning and can perform the art of living without being subjected to any coercive force. Even from the Rousseauian perspective from the book Discourse on Inequality, anarchism would be a straightforward proposition that stands as opposed to the formal social structures or institutions designed for governance. Hence, the economic and political elites always find the idea of anarchism anti-society. As the formal governing structures do not eliminate, but instead engender, socio-political inequalities, we should spontaneously unite for change—which the student protests repeatedly have indicated their potential for.

Research on mass uprisings in Bangladesh has always been analysed from the venture points of transferring political power, but the student protests show the possibility of a new life form. These protests shake the image of powerful sovereign authority and claim sovereign power ephemerally. Student protests reflect a horizon beyond state authority—a life form based on equality, justice and unity.

Mohammad Tareq Hasan is an anthropologist and teaches at the University of Dhaka. Currently, he works as a research fellow at the International Institute for Asian Studies (IIAS), Leiden University, the Netherlands.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments