Two women, one family, and divided nations

SUMATI'S STORY: PRE-PARTITION

Narrated by Sumati Guhathakurta

I was born in 1899 in the Raychaudhuri family in the village of Gabtali, Sonargaon, East Bengal. My father worked in the Treasury in Mymensingh. The single most important event of my growing years was my schooling. I went through ten years of education, ignoring my father's admonishments and social strictures and passed my Matriculation Exam in 1917 with flying colours. This was a time when the only girls who went to school without any moral reprehension were Christians or from Brahmo Samaj families.

When I was around 15 or 16, a marriage proposal from Kumudchandra Guhathakurta, a school teacher, came for me. He had an intermediate college degree, but he wanted to marry a girl who held a Matriculation degree. Even my dark complexion was exempted from criticism because of my educational qualifications.

SUMATI'S STORY: AFTER MARRIAGE

Narrated by Meghna Guhathakurta

After their marriage, their eldest son Jyotirmoy was born in 1920 in the suburban town of Mymensingh, where Sumati's father worked in the Treasury.

Kumudchandra and Sumati had spent eight years in Assam, where they worked as school teachers. But after returning from Assam, Kumudchandra contracted a spine disease and was paralysed. He died in 1935, leaving his widow Sumati to fend for their four children. Sumati stayed on at her father's residence in Mymensingh, and her children grew up together with her brother's large family of six children. Sumati also contributed to the family by working as a school teacher in the same school where she was educated, and when that was not enough, she sold many of her ornaments. All of her children had their schooling in Mymensingh.

Jyotirmoy was very bright, and he went to Calcutta Presidency College to do his Intermediate. Because of illness, he returned and gained admission in Dhaka, from where he received his M.A. in English Literature in 1943. He then became the primary bread earner when he got his first job at Ananda Mohan College in Mymensingh in 1944. He later shifted to Gurudayal College in Kishoreganj.

In 1946, Jyotirmoy joined Jagannath College in Dhaka. It was then that the family consisting of four children and the mother came and settled in Dhaka. They rented a house in Wari. In early 1947, Jyotirmoy married Basanti, the then Headmistress of a girl's school in Dhaka.

BASANTI'S STORY: PRE-PARTITION

Narrated by Basanti Guhathakurta

I was born in the village of Fatullah, Narayanganj. I was the fifth of six children. My school days began in the one-room village school. Later, I was sent to a 'proper' primary school for girls in Narayanganj.

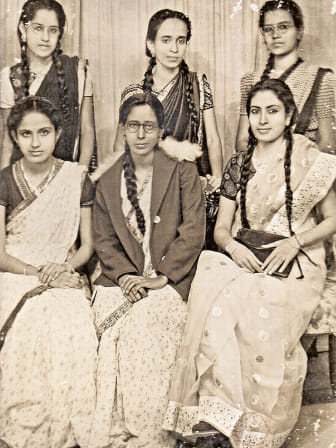

My thirst for learning grew as I passed from one grade to another. My family also sensed my determination to continue my education even after the socially accepted marriageable age for a girl was reached. My father, on his deathbed, beckoned my elder brother and bade him to let me study as long as I liked. My brother and his ever-growing family respected his words. Instead of getting married at 18 or 20 like many girls in my class, I went on to study at Eden Girls' College and then at the Bangla Department of the University of Dhaka.

It was while studying at Dhaka University that I met Jyotirmoy. We met through mutual friends. We participated in study circles at our Professor's house, and his sharp wit and articulation attracted me. We got married in 1947.

I had started my career as a school teacher before my marriage. After I graduated in teachers training in 1943, I taught at my old alma mater, Morgan Girls' School & College in Narayanganj. In 1944, I was offered the job as Headmistress of the then Gandaria Girls School, which later came to be known as Moniza Rahman Girls High School. It was here that I served as Headmistress till my retirement in 1987.

SUMATI'S STORY: THE EVENT OF THE PARTITION

Narrated by Sumati Guhathakurta

There were no major riots in the immediate aftermath of the Partition in Dhaka, just a feeling that Hindus should be leaving for India because the land no longer belonged to them. So many had departed to India only temporarily, leaving their houses intact.

It was only after the riots of 1950 that Hindus in Dhaka started to flee in large numbers across the border. But to leave or not to leave was something that was debated time and again in each family circle and did not abate with time.

In our family, too, the issue of possible migration was raised. Jyotsnamoy, my youngest son, and I were for leaving. My elder daughter Arati's wedding was being planned, so she was to leave for her new home anyway. My younger daughter Tapati was too young to have much of a say in this. But it was mainly Tapati's safety and security that was the top priority in our mind. But Jyotirmoy and Basanti had other ideas. They were both teachers and had many well-wishers among students and colleagues who urged them to stay. Jyotirmoy also had strong political convictions and was a follower of M.N. Roy's radical humanism. He was against the idea of Partition.

Hindu-Muslim riots started in late January, 1950. Suddenly, rumours of the killing of Hindus were heard in Dhaka. At that time, Arati was teaching at Basanti's school. When news about the riot broke out on that day, she was already on her way to school.

Arati learnt of the riots on the way and had got down at a friend's house. But the friend's house was attacked by an unruly mob, and they barely managed to escape by the back door. Later, they took refuge at a Hindu police inspector's house, which had virtually become a refugee centre. Since there was no safe way of communication at that point, Arati and others who took shelter like her spent the whole day and night in terror.

After spending a sleepless night, the next morning, Jyotirmoy asked his friend and neighbour Abdul Gani Hazari, who used to work at the Pakistan Observer, to help search for Arati. It fell upon Jyotsnamoy to accompany him because Jyotirmoy was too well known. Once Arati was found, she and Jyotsnamoy were brought to the office of the Pakistan Observer. At that time, the editor of the Pakistan Observer was Hamidul Huq Chowdhury. He was known as a 'riot-maker'.

Chowdhury offered to drive Arati and Jyotsnamoy home in his car. Jyotsnamoy was scared. Hazari assured him that he would follow the car in his jeep without letting him be seen. Chowdhury dropped them a block away from their home and asked them to walk the rest of the way. Jyotsnamoy thought that it was not safe and said they wanted to be dropped at the doorsteps. Chowdhury complied with the words, "You are very scared!"

After Arati's wedding, the Pakistan observer featured news titled, "Dhaka normal: Hindu Marriage Takes Place (29th February)." Arati's wedding had taken place as planned, in a curfew-ridden Dhaka. Only close relatives attended, and some Quaker friends of Jyotirmoy who were social workers attended the wedding.

After the wedding, a big meeting took place at the house—this time more heated than the 1947 debate on whether or not to leave. Jyotirmoy and Basanti wanted to remain, but this time I strongly held to my views that I should take Tapati and Jyotsnamoy and leave for Kolkata while Arati leaves with her husband to Bihar, where he was practising medicine. Jyotsnamoy tried his best to pursue Jyotirmoy and Basanti but to no avail. Basanti said, "You take your brother if you want to, but I have my own brother whom I cannot leave." So together with my son and daughter, I left for Kolkata around the last week of March, 1950. The decision to migrate was therefore made almost overnight!

BASANTI'S STORY: THE EVENT OF THE PARTITION

Narrated by Basanti Guhathakurta

When the Partition loomed ahead of us, both Jyotirmoy and I had decided that we should not leave. Jyotirmoy had retained close contact with M.N. Roy and his disciples in India, who advised him not to flee and remain in Dhaka. They argued that if educated people like them fled, they would merely add to the panic. Teachers were needed in the formation of a new state.

But this was a sentiment that we could not share with our immediate family. Jyotirmoy and I did not try to stop them. However, we knew that with Jyotirmoy being the sole bread-earner, maintaining a family across the border would prove to be a huge financial drain on our meagre salaries.

SUMATI'S STORY: MIGRATION AND ITS AFTERMATH

Narrated by Sumati Guhathakurta

Life for us in Kolkata was very uncertain. As soon as we arrived in Kolkata, we were handed a 'refugee slip' or a 'border slip'. We roamed around from one relative's house to another.

We heard that the West Bengal Government was offering land for the refugees. We got a piece of land. We had to build our own house or at least a semblance of it, and there was no electricity. We had to manage with whatever money was sent by Jyotirmoy. In this situation, around 1953, Jyotsnamoy got married and started living separately. Thus, Tapati and I had to look for shelter elsewhere. We finally found refuge with the family of Basanti's younger brother and his family in Jadavpur, Kolkata, where we rented a room for ourselves.

Sabita, my daughter-in-law, was also from a 'refugee' family, living in a house previously occupied by Muslims. When my son met her, she insisted that he become a graduate. Jyotsnamoy graduated in April 1955 from City College. My son claims that his wife brought some discipline into his bohemian life. He launched an engineering journal. He then spent his life trying to give his three sons the best of education so that they would not have to suffer like him.

In 1957, my daughter Tapati married Bimal Datta of Comilla, who worked in an insurance company. I also started to live nearby their house. Jyotirmoy provided for me by sending money across the border through people he knew as formal bank transactions were made more difficult as the days went by. My youngest daughter and son-in-law looked after me.

During the communal riots of 1964, we were apprehensive about Jyotirmoy and his family. To our great relief, when the Indo-Pakistan war broke out, they were all in England.

During the Bangladesh Liberation War, my son Jyotirmoy was killed. Our lives had changed drastically again, just as they had on the night during the riots of 1950.

BASANTI'S STORY: THE BUILD-UP TO 1971

Narrated by Basanti Guhathakurta

The Ayub regime registered an increasing hostility towards India and, along with it, towards Hindus in East Pakistan. Those who worked for a Bengali cultural identity were labelled 'Indian agents' by the Pakistani state. Jyotirmoy and I were not directly involved with any political parties, but we were part of a larger cultural movement that strove for freedom of expression.

Like many prominent Hindu community members, Jyotirmoy was blacklisted by the Pakistan state as being an 'Indian agent'. Men from the intelligence bureau were posted outside our house regularly. It was partly because of this that Jyotirmoy could not get a government scholarship to go abroad for higher studies.

It wasn't until 1963 that Jyotirmoy left for his higher studies at Kings College, London. My daughter and I then moved to my school quarters within the compound of Gandaria Girls High School.

In 1964, when communal riots hit Dhaka and its adjacent areas, my brother's family was especially affected. We first heard the news of riots from our local saree vendor, Muslim, who used to sell traditional jamdani sarees to our family since the time of his father. He had come from the Narayanganj area and had seen several villages ablaze. I immediately thought that Fatullah might also be affected and sent Muslim to my village home by train. That evening Muslim returned with forty Hindu women and children, all seeking shelter under my roof.

The next morning, the police escorted forty women to the 'riot shelter'. We spent seven days in that dilapidated shelter home. On the eighth day, the curfew was lifted, and we went home. Jyotirmoy had been anxious about us all through this period, and now, I started seriously to apply for the work permit to teach in England.

We were in England during the 1965 Indo-Pakistani War, but my brother was put under house arrest on the charge that he was allegedly seen showing a lantern to Indian planes during a blackout! It must be mentioned that the actual war was being fought on the western front, and not a bomb was dropped in this region. After that incident, my brother also started thinking of selling off his property and leaving for India. By 1969 they all left East Bengal.

We decided to return to East Pakistan since Jyotirmoy had taken a loan from the University. He felt that he had to return to pay it back from his salary.

We came back to Dhaka in January 1967. We had barely settled down, when Jyotirmoy who had given his passport for renewal, was informed that there was an instruction from the Central Government that no new passport was to be issued to him. This angered him. He had wanted to go to India to see his mother and was frustrated by this measure. To deny him a passport was to deny him basic citizenship rights.

After the Indo-Pakistan war of 1965, air travel between Dhaka and Kolkata was discontinued. Since Jyotirmoy could not go, it fell upon my daughter and me to make an arduous land journey across the Benapole border once a year to keep in touch with the family. Once, I brought my mother-in-law with us to see her son. She endured the painful journey since it was the only way she could see her son.

In 1970, Jyotirmoy was made provost of Jagannath Hall. At that time, we shifted to the University campus.

On the fateful night of 25th March 1971, three soldiers came in through the back door, asked for Jyotirmoy, and took him away. They asked him his name and religion at gunpoint and gave the order to shoot. They left him outside our house. He was conscious for four days. We could only take him to the hospital after a whole day and two nights. Jyotirmoy succumbed to his injury on 30th March 1971.

We could not even get his dead body. The Pakistan military surrounded the hospital and was keeping an eye on those wounded by bullets. The whole country was thrown into war. Throughout the nine months, we took shelter under different roofs, often under different names, for our identity as Hindus and as families of the 'executed' was enough to put ourselves and our friends in danger.

On various occasions, I was offered escort to India as thousands were fleeing the border. But I resisted. I felt I had to prove Jyotirmoy's death. When I went for his death certificate, the hospital authorities stated that pneumonia was the cause of death. I distinctively remember that it was originally written as death by bullet wounds. This was the first indication that our history was being systematically erased, and I felt that the truth would never come out if we left.

SUMATI'S STORY: THE RETURN

Narrated by Sumati Guhathakurta

When Basanti and Meghna came to Kolkata on one of the first flights from independent Bangladesh, the whole family went to receive them. We could only listen with horror as they related stories of their trials and tribulations during the nine-month war. But now, the crucial question was to decide their future. Basanti, as staunch as ever, told us that Bangladesh was the only place where she could think of staying. Meghna, too, stood by her mother and refused to be separated from her. It was then that the family decided that I should go with Basanti and Meghna to Bangladesh. By that time, legal migration was not allowed between the two countries, except in cases of marriage. But I was old and would live as a dependent of Basanti, so perhaps it would not be a problem for me. So, I left Kolkata after twenty years to return to a homeland that I had learnt to regard as strange and foreign. After I reached Dhaka, I discarded my Indian passport and applied for a Bangladeshi one as the mother of my martyred son.

Even after all these years, I feel we have been carrying the burden of the Partition. It is a burden, which I feel I would carry with me all the way to my funeral pyre.

Postscript

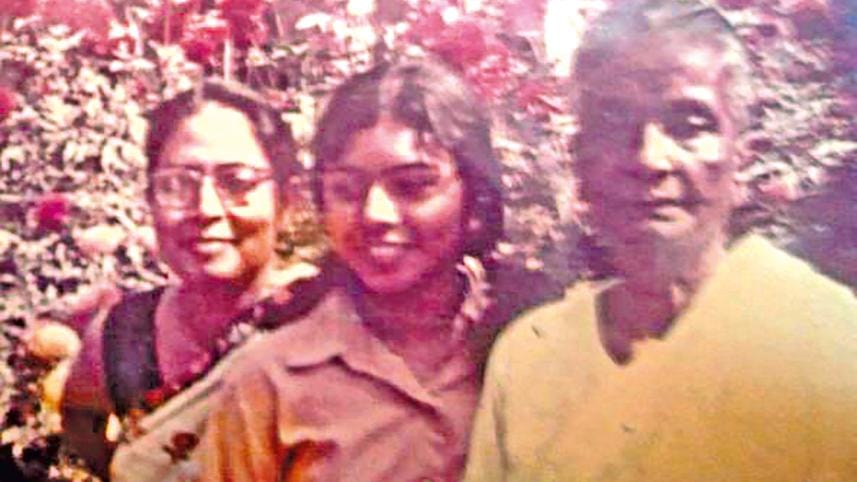

Narrated by Meghna Guhathakurta

My grandmother, Sumati Guhathakurta, died in January 1985 in Dhaka at the age of 82 after spending her life alternatively in Dhaka and Kolkata. My mother, Basanti Guhathakurta, died in September 1993 at the age of 73 in Kolkata, where she had gone for medical treatment for cirrhosis of the liver. She had dedicated her whole life to her school, students and family in that part of the world that came to be known variously as East Bengal, East Pakistan and Bangladesh. The Partition of 1947 had wreaked havoc in their lives and the lives of the people they knew around them. Yet, like the lives of many great women of this world, theirs bore the mark of the strength, wisdom, generosity and gentleness of women who had to struggle against time and tide to make meaning out of their existence, not only for themselves and their families but for generations to come.

Meghna Guhathakurta taught International Relations at the University of Dhaka from 1984 to 2007. She is currently the Executive Director of Research Initiatives, Bangladesh (RIB).

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments