Tagore’s idea of nationalism

If you look for a definition of the word 'nationalism' on Google, or in an encyclopedia, you will find quite a few. However, this word, like many such words, is 'notorious' in its own way, as no single definition seems to define it thoroughly. It assumes different meanings in different contexts. And such contexts are countless. Feudalism, with its many faces, is one. Colonial rule is another, which itself has numerous varieties—colonization in the Americas or Australia cannot be compared with that of India or China. And an independent country cannot dispense with nationalism either; it must build up its own brand or brands.

Tagore was born and lived his whole life in a colonial country, then undivided India, which can be roughly identified with the modern South Asian subcontinent. It had long been under feudal control, to be replaced by British imperial occupation of India after a brief period of mercenary masquerade. A hundred years after the Plassey defeat of 1757, an attempt was made to replace the White occupation. This was a bid to revert to traditional feudalism, in the form of a mutiny. However, it failed. Rabindranath Tagore was born three years later, soon to become an imperial subject with the rest of his countrymen.

2

Growing up, like some of his fellow citizens, he had a love-hate relationship with the rulers. In the course of time, he had opportunities to study them from up close.

He, as a boy, would share the patriotism of his family and wish that his country were free. He would write poems about its past glory and present indignity as a subject-race. Beyond his singing 'Bande Mataram' in Congress conferences, his active participation in movements against the decisions of the rulers would come much later, in 1905. It was during the movement against the first Bengal Partition when he took to the streets.

Till the late 1880s, he seemed to be leading a life of leisure, writing romantic poems, composing songs and creating and staging operas, both sombre and jubilant.

This of course, is just one side of the picture. He wouldn't turn his back on what was happening in his country and in rest of the world. In 1881, he published an article called 'Chine Maraner Byabosay' (Trade of Death in China), in which he wrote about the evil perpetrated by the British in China in forcing the latter's people to produce and consume opium. This was taking place against the wishes of the Chinese. He also composed some patriotic songs, lamenting the insensibility of the sons of the country who didn't care for her degraded state.

Patriotism was palpable in Bengal in the middle of the nineteenth century, and was being propagated in literature and theatre, with, I am afraid, unconscious implications of communalism. This may have been prompted by a book of Colonel James Todd called Annals and Antiquities of Rajasthan (Vol. 1, 1829), which, back then, had a great influence on the educated Bengali Hindu. The poems, novels and plays of men like Rangalal Bandyopadhyay (1827-1887), Bankim Chandra Chatterjee (1838-1894) and Jyotirindranath Tagore (1849-1925) were notably patriotic. Most of them portrayed the Muslim rulers of the past as enemies of India's independence. The paradox was that during that era India was subjugated by the British.

There were exceptions like Dinabandhu Mitra (1829-1874) and Upendranath Das (1848-1895). Albeit, the aforementioned trend eventually led to a 'communal divide' in the freedom struggle, and ultimately to the Partition of India in 1947.

The Indian National Congress was founded in 1885, till which time Tagore did not involve himself in politics. His contribution to social movements included writing songs and poetic pronouncements. However, with his move to mid-Bengal to manage and administer the expansive Tagore estates, a sea-change was reflected in his attitude towards his country and its people. He realized that Congress ambitions did not exhibit the desires of the nation, the people and those at the lower echelons of society. He had learned of a 'country-commoners' equation from a Japanese patriot, Yoshido Toraziro. Tagore had probed into the life of Toraziro, reading about the latter in Robert Louis Stevenson's book Familiar studies of Men and Book.

Tagore speaks of Toraziro in his 1905 lecture 'Chhatrader Prati Sambhashan' ('Address to the Students). "...when Toraziro had decided that he would dedicate his life for his country, he asked himself, 'Do I know my country?' Searching for the answer, he treaded along the roads of Japan for three years, living in the huts of peasants and fishermen. At the end of it, he realized that to know Japan it was pivotal to know its people. He decided that he must devote his life's work to the underprivileged. He did and the feudal rulers hanged him for that."

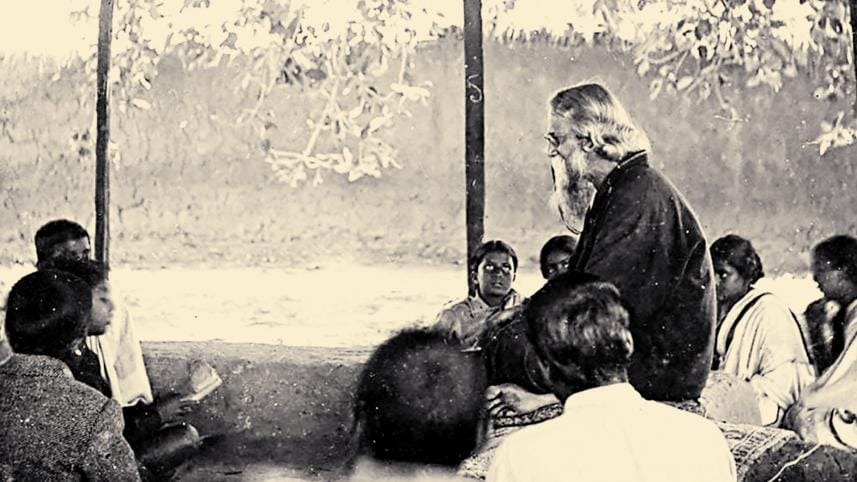

Tagore did not have to travel the whole country (nor was he hanged, mercifully), but his sojourn in East Bengal did the trick for him. He discovered the real India. It was the nation where both, the Tagore estates and deprived and oppressed subjects, were located. His efforts to uplift the masses have been chronicled elsewhere and I would not like to expand on that.

How Tagore perceived the state of the nation is amply clear from two telling statements from the same article, in which he juxtaposes the 'imagined' and the 'real' country.

"To imagine that Mother India is sitting on a peak of the Himalayas and strumming a melancholic tune on her Veena, is to hallucinate. But (instead), the Mother India in our village, sitting on the porch of her hut by the mud-full and weedy pond, and vacantly looking at her empty cupboard. On her lap is her malaria-struck son with a spleen. This deserves our keen attention. One distant greeting is enough for the (one) Bharat Mata that is watering the troughs of the Shami trees in the hermitages of Vyasa, Vishwamitra and Vashishta. But the (other) Bharat Mata in tattered clothes, who is hungry or half-fed, is cooking away in others' kitchens, so that she can send her son to an English school. All this to acquire for him the insufferable life of an office clerk. This deserves much more than a mere greeting."

The portrayal of a suffering woman in both the instances is doubly significant, as women in this region once occupied the lowest of the low positions in households and the society.

This form of nationalism is characterized by 'inclusiveness,' at a time when the society was deeply marked by the absence of it. Tagore did not care about which religion a person belonged to. It did not matter to him whether they were Hindus or Muslims. The communal divide had caused him much agitation. Often, his writings criticized Hindus for their high-handed social insensitivity. His vision covered both horizontal and vertical dimensions, as he focused more on the underclasses, irrespective of their communal identity. His poem 'Bharat-tirtha' and the song 'Jana-gana-mana' bear witness to this truth.

3

Looking from the inside of the national boundary, this was Tagore's idea of a nation. It was not just a geographical entity, a map or a beautiful,bountiful and natural expanse. A nation was to be fundamentally honored as a space full of people. Tagore's outlook was not selfishly limited to his own class, but moved beyond and below his social status. Tagore's perspective included those for whom liberation or independence did not mean having good jobs, but entailed surviving with dignity, on equal terms with others.

Tagore embarked on his own 'journey' of nationalism. He was committed to changing the lives of his subjects, a campaign which was later dubbed as 'reconstructive nationalism' by historians of the national movement. A mere two-word term such as this cannot give us any idea of the love and passion that was behind his works and pronouncements.

Tagore's 'nationalism' has to be also defined by moving beyond the national map. He kept himself abreast of the happenings outside his country. Some of his poems in Naibedya (1901) alert us about imperialism that was tearing Africa asunder during the Second Boer War (1899-1902), which he felt would lead to greater world catastrophe. This was perhaps the juncture at which he discovered the limitations of nationalism and the potential dangers of its excesses.

Here, the following question has to be posed: How does one place one's country among other countries and the peoples of the world?

In this regard, a general approach is, "My country is the best country in the world, and others can't simply touch its unique glory and acquisitions!" There are many national songs and anthems which depict such themes and there is probably nothing wrong with that.

Poet Dwijendralal Roy has a famous and popular song called "Dhanadhanya Pushpe Bhara Amader ei Basundhara" that carries such a strain. That is all right. When a country is under alien rule and the morale of the countrymen is low, such songs are essential. In times of prosperity, these very songs have the potential of evoking pride.

Nervertheless, privileging one's own country may also lead to dire consequences. It may prompt imperialistic designs, as history of the world has extensively displayed. Hitler's Germany can be cited as an example. The British patriotic song 'Rule Britannia' was not an 'innocent' song either.

Tagore was cautious to avoid themes which were not called for. He had said that he was blessed to be born in this country and that he loved his golden Bengal. He had asserted that he would place his head on the soil of his country; the soil on which the all pervading earth-mother's sari hemline was spread. For Tagore, his country was borderless; the world contained it, as it contained the world. He had a home in every country and he would seek out that home at will. There were no 'us' and 'others' for him. According to his beliefs, we were all one, in existence together. Moreover, this inclusive philosophy was not limited to the human world alone. It contained other living beings, the living environment, the non-living part of the universe, the hills, rivers and the sky with its stars and planets. In light of such viewpoints, it is apt to quote the following lines from Tagore's Gitanjali:

The same stream of life that runs through my veins

night and day runs through this world

and dances in rhythmic measures.

It is the same life that shoots in joy

through the dust of the earth

in numberless blades of grass and

breaks into tumultuous waves of leaves and flowers.

It is the same life that is rocked

in the ocean-cradle of birth and of death,

in ebb and in flow.

Once life is visualized through a lens of interconnectedness (with everyone and everything), isolationaism, typically a component of traditional nationalism, seems unappealing.

4

Towards the end of his life, he had fittingly said, 'I am the poet of the world. Wherever there is a stirring in it, you'll find an echo in my flute'. Some years ago, he had begun his lectures on nationalism. The book 'Nationalism' (published in 1917), which did not please many, was a venture in that direction.

The Japanese and the West were angered. Indians, too, had questions of their own. During the First World War, his words were mostly ignored.

It was soon evident that another world war was brewing. As a precursor to that, Japan invaded China. Japanese poet Yone Noguchi was bold enough to seek Tagore's support . Japan was planning to establish an Asian empire ruled by the Japanese.

Tagore wrote back in anger, "in launching the ravening war on Chinese humanity, with all the deadly methods learnt from the West, Japan is infringing every moral principle on which civilization is based…You are building your conception of an Asia which would be raised on a tower of skulls…China is unconquerable"…

And he concluded by saying, "I wish for your people, whom I love, not success, but remorse."

One still wonders how to define Tagore's kind of 'nationalism.'

Pabitra Sarkar is an Author and former Vice Chancellor of Rabindra Bharati University, Kolkata.

Send your articles for Slow Reads to slowreads@thedailystar.net. Check out our submission guidelines for details.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments