Dhirendranath Dutta: Portrait of a patriot

Dhirendranath Dutta was born on November 2, 1886 to a lower middle-income family in Ramrail village of Brahmanbaria sub-division under Tripura district, now known as Cumilla. After receiving primary and secondary education in the district, Dhirendranth moved to Kolkata in 1904 and gained admission to the city's Ripon College, founded by Surendranath Banerjee, who is widely regarded as the father of Indian nationalism.

During his early life, Dhirendranath was inspired by Pundit Ishwar Chandra Bidyasagar's fearlessness, selflessness, and devotion to his mother. Another book that made a lasting impression on him as an adolescent was Ashwini Kumar Dutt'a Bhaktiyoga. In those days, Dhirendranath was deeply saddened by the widespread prevalence of superstitions in rural societies – child marriages, chronic indebtedness among the peasantry, and untouchability.

Dhirendranath was so disturbed by the practice of untouchability that he often dared to stand against classmates, village elders, friends and even his own father whenever he saw them engaging in or justifying this heinous act. He also continuously strived to shade off his conservatism about social and religious practices.

At a meeting in 1914, Dhirendranath aired his voice against Hindu widow-remarriages but after realising this was a reactionary and regressive position, he regretted it for the rest of his life.

It is interesting that in his autobiography and elsewhere as well, Dhirendranath identified farmers, fishermen and other toiling masses as the creator of wealth. Many Hindu fishermen who inhabited Nabinagar at that time were pejoratively called "Gabor", or filthy, by the upper-caste people. To Dhirendranath, this society of fishermen was the greatest wealth creator. Throughout his political career, he had been especially aware and concerned about the fishermen community of Brahmanbaria.

After partition, when the East Bengal government decided to reform the Bengal Fisheries Preservation Bill to acquire rent receiving fisheries of the province and lease them out to the highest bidders, Dhirendranath took special care and urged the government to not deprive fishermen of their livelihoods to the benefit of non-fishing middlemen.

In those tumultuous days of the Swadeshi Movement against the first partition of Bengal, he cut his political teeth by joining the Kolkata Session of the All India Congress Committee as a volunteer.

But already during that charged atmosphere of patriotism, not least due to Surendranath Bannerji's lecture in the college, he developed political consciousness, and ideas like self-sacrifice for the cause of the nation, altruism and benevolence.

The congress politics of that era was characterised by two opposite factions, namely the extremists and the moderates.

In his posthumously published autobiography he writes, he spent most of those days reading journals and periodicals published by the extremists but politically he was drawn towards the moderate faction of the Congress despite knowing the limitations of their methods.

During that time, the young Dhirendranath joined the Kolkata-based "Tripura Hitasadhoni Shabha" -- an organisation dedicated to spreading education among the women of this district, a cause he upheld all through his life. Subsequently, Dhirendranath became the secretary of this organisation in 1906 while another eminent nationalist leader and native son of Brahmanbaria, Abdur Rasul was president.

The latter was a lifelong inspiration for Dhirendranath in doing philanthropic and social work. He mentions his "guru" Abdur Rasul with much reverence. Rasul once told the young Dhirendranath that he wanted to retire from life in Calcutta and live among the poor masses and devote his entire time for their betterment.

Dhirendranath's tribute to his guru was not a mere platitude, rather he put into practice what he learned all through his life. Upon completing his education in Calcutta in 1910, he returned to Cumilla.

First, he joined a school in a rural area as an assistant teacher and a few years afterward joined the bar -- which was considered as the most appropriate profession for any politician.

Although as a politician and parliamentarian he had to stay in Kolkata before partition and Karachi and Dhaka after it, he never thought of leaving Cumilla, nor even acquired any property in those places. As such, Cumilla had been his permanent residence till death in 1971.

Quite early in his career, he established himself as a successful lawyer in the district. He practiced law earnestly and uninterruptedly from 1911 to 1920. Dhirendranath's reputation as a lawyer was akin to legend due to the service he provided for the poor.

Dhirendranath actively joined politics during the Khilafat-non-cooperation movements of 1920-21. At a mammoth meeting held in Cumilla town on March 6, 1921, Deshbandhu CR Dash called the lawyers of the province to boycott courts.

Dhirendranath abstained from attending court for three months. During this period, he kept himself busy by organising Congress volunteers. As a part of his duties in the Brahmanbaria subdivision, he worked to propagate messages of the Congress party, the importance of maintaining Hindu-Muslim unity and popularising Khadi as well as campaigns against untouchability. Throughout the movement, he treaded along the muddied roads of that part of rural Bengal, leading his volunteer bahini and organising many protests and processions. Through these acts, he familiarised himself with the villages. Many of his fellow Congress workers and leaders were arrested and put behind bars but luck did not "favour him this time".

Once the surge of the Non-cooperation Movement ebbed away Dhirendranath got involved in the activities of organisations like Abhay Ashram and Mukti Sangha in Cumilla. He also resumed legal practice.

He was especially instrumental in forming Mukti Sangha to get rid of untouchability. He established a branch of Abhay Ashram in the Bhelkut union of Nasirnagar in 1936 to spread education, consciousness and unity among the Namasudra fishermen.

When again the Indian National Congress called for the civil disobedience movement in 1930, Dhirendranath led the movement in Cumilla. He led a huge procession of more than one thousand women in a town as small as Cumilla. In so doing, he not only had to confront police brutality on the streets, but was arrested too for the first time and sentenced to rigorous imprisonment for three months. This jail-life made him more resolved to fight for the country and provided him with the experience that equipped him to live behind bars and under house arrest a few more times in the years to come.

People who knew Dhirendranath identified him as a man of faith, character and conviction, both in his political and personal life. In politics, this particular predilection of Dhirendranath had flown through the channel of constitutionalism and democratic rights in the context of colonialism. For many politicians of the era, participation in the parliament and assembly was an important step in the politics of constitutionalism.

Dhirendranath was widely considered as a deft and eloquent parliamentarian. His parliamentary career began in the Bengal Provincial Assembly elections of 1937. The Government of India Act, 1937 ensured the formation of a certain kind of responsible government in the provinces for the first time in India.

He was elected to the assembly from a "general seat" in Cumilla, defeating Kamini Kumar Dutta, a prominent lawyer of the district and future Law and Health minister of Pakistan. He returned to the assembly in the 1946 elections too, this time defeating the Hindu Mahasabha candidate by a wide margin.

Between 1937 and 1947, as a prominent leader of the Bengal Provincial Congress Committee Dhirendranath got involved in agitations as usual. He was incarcerated for almost a year for his involvement with the Quit India Movement launched in August 1942.

His philanthropic and social works continued unabated, notwithstanding the immense pressure of organisational responsibilities. During Partition, Dhirendranath was the deputy leader of the opposition in the Bengal Provincial assembly led by Kiran Shankar Roy.

The decision to partition Bengal and Punjab between the Hindu and Muslim majority areas based on the "principle of contiguity" was taken on June 3, 1947.

Dhirendranath's political activism and all the trials and tribulations from the Swadeshi era to the days leading up to the transfer of power by the British colonial government had been directed to an independent, undivided India which was the declared official position of the Congress party.

Therefore, in many respects, partition and the establishment of Pakistan was demoralising for Dutta as it was for many of his colleagues. Dhirendranath then decided to join the Constituent Assembly of Pakistan.

He could have easily joined the Legislative Assembly of West Bengal or the Constituent Assembly of India as many others did, but he decided to stay back in Pakistan and work for her as a "true Pakistani in mind, words, and deeds".

To understand why he took such a decision, we need to take into account what principles and ideals guided his political career.

We have already seen how deeply he was attached to the people of Cumilla irrespective of their religion, caste and class. He did not want to leave behind his political comrades, friends, relations, not least the poorer sections of the Hindu community who were scattered in large numbers in erstwhile Tripura district.

As he ardently believed "you cannot love your country unless you love mankind". To him, serving the people of his birthplace was the best way of doing politics. Neither was he motivated or guided by the desire of securing a high political position.

Although he became part of political factions and groups, contested elections, and held portfolios at times, he never seemed to have lost sight of this fundamental postulate of politics.

He wrote in his autobiography about the much-cited speech of Muhammad Ali Jinnah on the inaugural day of the Constituent Assembly of Pakistan on August 11, 1947, where he said all majorities and minorities alike would be treated as Pakistanis without discrimination, saying that it had assured him to some extent.

Notwithstanding the violence, displacement and devastation resulting from partition, given the fact that India and Pakistan are finally free from the yoke of prolonged colonial rule, it was not unnatural to be hopeful about a new beginning. Therefore, with partition in an altered state of reality he plunged into an uphill struggle.

The name Dhirendranath Dutta is inextricably linked with the language movements that, according to many historians, led to a cultural efflorescence in East Bengal which in turn paved the way for the establishment of Bangladesh.

On February 25, 1948, during a discussion on the Rules of Procedure of the Constituent Assembly, Dhirendranath in his speech ignited the debate on the lingua franca of Pakistan, which subsequently had a far-reaching impact on the course of the language movement.

In his amendment motion, Dhirendranath demanded that in sub-rule (1) of rule-29 along with Urdu and English, Bengali should be included in the proceedings of the Constituent Assembly, which was also functioning as the central legislature of Pakistan.

As a justification behind the need for such an amendment, he went on to say that "of the roughly six crore and ninety lakh people inhabiting the state, four crore and 40 lakh spoke the Bengalee language".

"So sir, what should be the state language? The state language should be the one which is used by the majority of the people of the state and for that, I consider that Bengalee is a lingua franca of our state," he said.

Dhirendranath clarified he didn't move this proposal in a "spirit of narrow Provincialism" but rather, "in the spirit that this motion receives the fullest considerations at the hands of the members present".

As always, on this occasion too, Dhirendranath Dutta raised the question of the sufferings and inconveniences of ordinary people of East Bengal in their everyday life due to train tickets, stamps, money order forms being printed in the Urdu language alone.

He asked if money order forms were not printed in Bengali, how a poor cultivator in rural Bengal would send money to his son studying at the then Dacca University. He was fully aware of the fact that among students and intellectuals a discussion had already begun for making Bengali the official language and medium of instruction in the province and educated youths of the university were playing a pioneering role, going as far as to form an action committee in December 1947.

Dhirendranath later acknowledged that it was not an official decision of the Congress party; he raised the issue on his own. But once the amendment was motioned, voices were being raised by many of his party, among others, Prem Hari Barman and Bhupendra Kumar Dutta being among them.

All the Bengali members of the government party opposed Dhirendranath in unison. Liaquat Ali Khan, the prime minister of Pakistan, rightly understood the far-reaching implications of Dhirendranath's demand made at the constitution-making body of the country.

He said he wished Dhirendranath "had not moved his amendment" and accused him of trying to "create a misunderstanding between the different parts of Pakistan".

Ignoring the very reasonable proposal of Dhirendranath, Khan preemptively said that being a Muslim nation, only the language of a hundred million Muslims of the sub-continent which was Urdu according to him would be the lingua franca of Pakistan.

Khawaja Nazimuddin, the Prime Minister of East Bengal, confidently claimed that "the overwhelming majority of the people are in favour of having Urdu as the state language of Pakistan as a whole".

Dhirendranath's motion was negated at the assembly but it struck a chord with a wide range of people outside the parliament. Outside the assembly, the demand to make Bengali one of the official languages and medium of instruction till then was limited to a close circle of students and intellectuals. Dhirendranath's speech provided the proponents of Bengali with the opportunity to reach a wider section of the people.

The deafening silence of the Bengali representatives of the government party and the reactions of Liaquat Ali and Khawaja Nazimuddin made people immensely angry. On the following day, students of Dhaka University, Medical College, Jagannath College and Engineering College, as well as from many schools spontaneously took to the streets and called for a province-wide strike to be held on March 11, 1948.

He again raised the issue on April 6, 1948 at the East Bengal Provincial Assembly in which he was deputy leader of the opposition.

When Khawaja Nazimuddin moved the government resolution "Bengali as Official Language and Medium of Instruction" at the house, which was a highly petered out version of the accord he had struck with the Action Committee on March 16, 1948, Dhirendranath brought forward three different amendments in the resolution.

He proposed that in the government resolution, the clause "the assembly is further of the opinion that Bengali should be one of the state languages of Pakistan" be included.

He urged the assembly to recommend the central government to introduce Bengali immediately in all currencies, telegraphs, postal stamps and official documents.

Another demand by way of amendment was including a clause in the resolution, urging the central authority to introduce Bengali as a medium and one of the subjects for all competitive examinations.

Dhirendranath might have thought in a more familiar milieu of the provincial assembly in the wake of such a widespread agitation he would be able to pursue the government side, but all his motions were rejected on the ground that these issues were beyond the jurisdiction of the provincial government.

Not only that, one assembly member attacked him for being "intolerant in his advocacy for the language of Bengali".

His activities were not limited only to the question of language. He was one of the earliest proponents of a joint electorate in Pakistan. For the minorities of Pakistan, not least the Hindus of East Pakistan, introduction of a joint electorate meant a considerably diminished number of central and provisional assembly seats.

But Dhirendranath pushed for it strongly on the ground that a non-communal form of politics would be better for the minority community despite most of his colleagues' vehement opposition.

He wanted to speak not only for the minorities but for the people of every other denomination too. In the central legislature he fought tooth and nail on every issue where the interests of East Bengal, which he terms as "my unhappy province" on several occasions, was at stake.

He served as minister of medical, public health and social welfare during the chief ministership of Ataur Rahman Khan. In his less than two-year tenure of ministership, he took many important initiatives to expand the public health infrastructure. Among others, he helped establish medical colleges in Rajshahi and Chattogram, as well as tuberculosis and community clinics in many other places.

Dhirendranath suffered at the hands of the people of power throughout his political life. In the pre-partition decades he was incarcerated and detained. In Pakistan, he was branded as a traitor who was out to destroy the country. Between 1947 and 1954, both in the central and provincial legislatures most of the time Dhirenranath was the main aim of verbal attacks and criticism from the government side but he never backed down from the position he deemed to be right.

During the military rule he was banned from politics, put under house arrest and his passport was put on hold, and the ultimate price he paid for his commitment was his life.

On March 29, 1971, the eighty-five-year-old Dhirendranath was arrested from his house along with his son by the Pakistan military and taken to Comilla Cantonment.

Their mortal remains have not been found since. Like he was the first proposer of Bengali to be one of the state languages of Pakistan and one of the pioneers of the joint electorate and non-communal politics in Pakistan, it was no happenstance that he was the first and perhaps only politician of his stature to be martyred in the Liberation War of Bangladesh.

Mohammad Afzalur Rahman is currently pursuing his PhD at Jawaharlal Nehru University. He can be contacted at ar8886@gmail.com

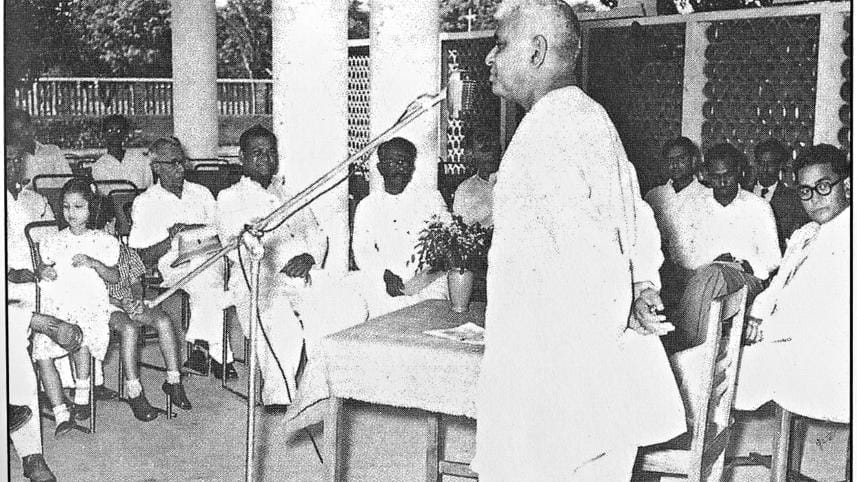

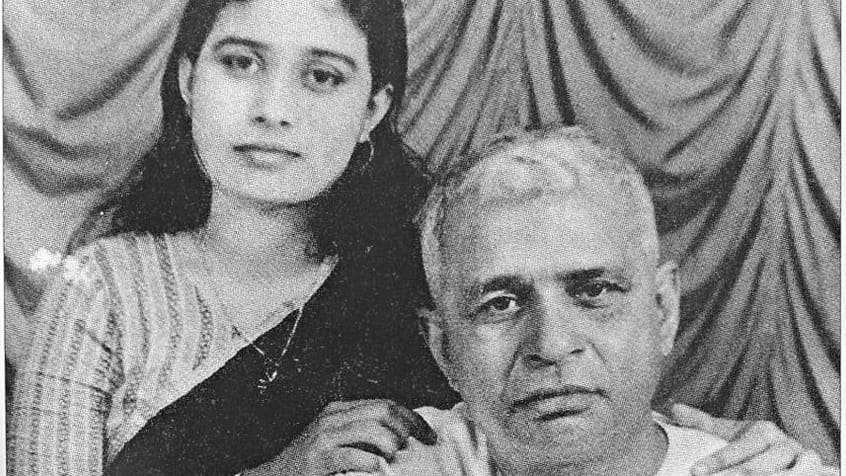

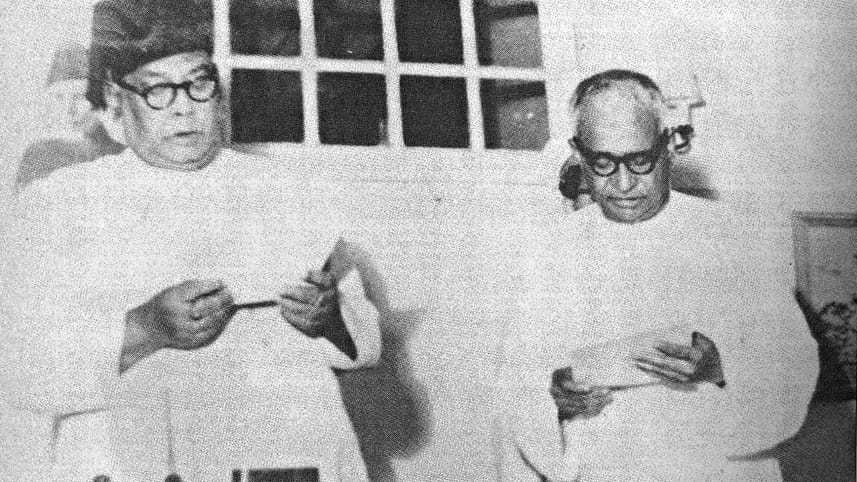

Photo courtesy: Shaheed Dhirendranath Dutter Atmakatha.Journeyman Books, Dhaka, 2020.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments