At Freedom’s Gate?

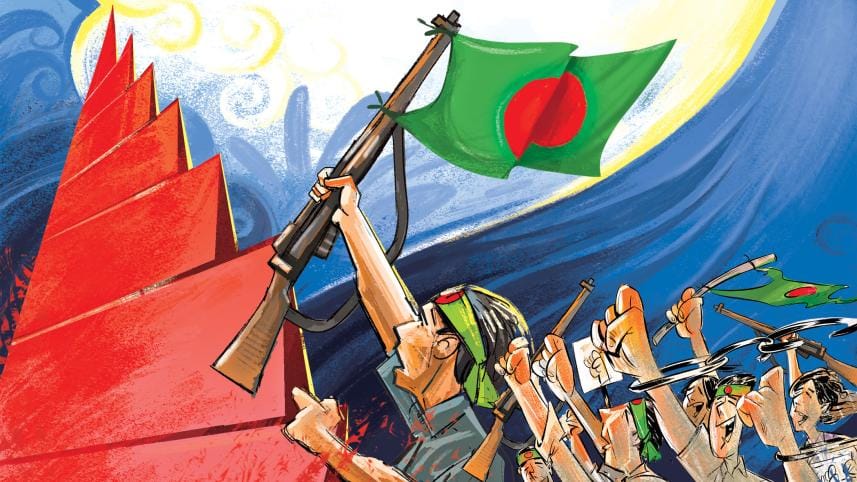

Fifty-three years ago, Bangladesh won its independence after a bloody nine-month war with Pakistan. December 16, 1971, was a day of unparalleled euphoria. I still remember running through the streets with friends, waving the Bangladeshi flag. We laughed, cried, danced, and shared sweets. Strangers embraced strangers. On that day, we were all united in joy and hope. Yet it did not take long for this euphoria to be replaced by a state of economic mismanagement and rising political oppression. In the last fifteen years, that has turned into a state of terror under Sheikh Hasina's rule.

The Monsoon Uprising of August 5, 2024, has been called by many names: revolution, Bangladesh 2.0, the birth of a new republic. What began as a student-led protest against the government's decision to reserve employment opportunities for the descendants of freedom fighters—widely perceived to benefit the supporters of the ruling Awami League—quickly morphed into a nationwide movement fueled by intense anger and frustration. What is more surprising is that the question of employment for young people soon disappeared from the movement, replaced instead by demands for reforms of the constitution and state bureaucracy.

Watching these historic events on my iPad—since I don't own a television—has been nothing short of an out-of-body experience. In the later stages, the uprising became rhizomatic, drawing people from all walks of life: students, teachers, parents, artists, shopkeepers, garment workers, rickshaw pullers, and countless others joined the movement, embodying a collective desire for change. Yet, I hesitate to call this a revolution. Few anticipated the sudden fall of Sheikh Hasina's authoritarian regime, the establishment of an interim government led by Nobel Laureate Professor Yunus, or the growing momentum behind student-led demands for democracy and free speech. After 15 years of political repression, the nation witnessed a profound hunger for open dialogue and the freedom to express oneself without fear. This sudden and radical change in power came without a clear roadmap of next steps. We have heard of a Mastermind of the movement but not of a Master Plan.

However, I do not see the Uprising as a revolution. A revolution entails a systemic transformation of a nation's political and economic structures, like the Cuban Revolution, which shifted from the ideological framework of sugar plantations to communist rule. The Monsoon Uprising, by contrast, was fundamentally a revolt against political oppression: the denial of free elections, the erosion of voters' choice, and the monopolization of power by a single political party. The Uprising is fundamentally a call to replace a corrupt and repressive government with the rule of law and democratic elections, but not a systemic change in the political and economic apparatus. We remain in a neoliberal trickle-down economic structure.

Post-August 5 reflects the people's call for free and fair parliamentary elections, the elimination of government corruption, and a renewed respect for the dignity of life and free speech. These are noble and universal objectives cherished by all freedom-loving individuals. Yet, what reforms are people asking for? What kind of transformation do they envision? And what gaps, if any, remain in this demand for political change?

In my opinion, the current political discourse misses several fundamental concerns that are essential for a true people's revolution. Absent are demands for equitable wealth distribution, support for trade unions, employment opportunities for our growing population of unemployed and underemployed youth, and investment to bridge the economic gap between urban and rural areas. After all, citizens of a poor country think of food and employment before constitutional reforms and free speech. Below are three critical points I wish to highlight:

Where are the Farmers?

In a country where 50-60% of the population depends on agriculture, the exclusion of farmers from this new political framework is glaring. I have not seen any serious effort to address the challenges faced by the agricultural labor force. No political representatives or leaders in this movement are advocating for the peasantry. Since the passing of Maulana Bhashani, no national figure has championed the cause of farmers in Bangladesh. Where are the promises for better credit systems, seeds, fertilizers, and fair crop prices? What about their aspirations for a Bangladesh that safeguards their rights? Why do we so easily forget those who put the rice on our table?

Where are the Mofussil Students?

What began as a student-driven initiative has failed to extend its reach to include students from provincial towns. Today, the movement is largely urban and dominated by leaders from Dhaka University. This excludes the voices of students from mofussil regions, whose needs often differ from those in the capital. Issues like inadequate facilities, lack of proper classrooms, libraries, Internet access, and underqualified teachers plague these institutions, leaving students ill-prepared for the 21st century. This perpetuates inequality in opportunities, deepening the urban-rural divide.

How Secure is the Hindu Community?

The recent arrest of Chinmoy Krishno Das and the subsequent wave of disinformation in Indian media have sparked communal tensions across our border, catching both the interim government and local media off guard. With Bangladesh no longer its vassal state, the Indian government and media are hell-bent on destabilizing the interim government. The reports of mass violence against Hindus from Indian media are exaggerated, but it cannot be denied that a climate of fear persists within the Hindu community. Yet, on TV talk shows, I hear a blanket denial of persecution. Conversations with Bangladeshi Hindu friends in the U.S. reveal heightened anxiety among their families back home. Fear—not just persecution—is equally chilling, particularly in rural areas where minority communities feel increasingly vulnerable. It behooves the Bangladeshi media to report from all parts of the country on the state of the Hindu community. Do they feel safe? Do they feel besieged? Do they think they will lose their property? These are essential questions to address through empirical evidence.

For Bangladesh's political transformation to succeed and establish a democratic state, the movement must genuinely represent and protect all its people. Without such inclusivity and action, the Monsoon Uprising risks fading into irrelevance. After all, history reminds us that monsoons are often followed by droughts.

Lamia Karim is a professor of anthropology at the University of Oregon, Eugene.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments