Connetts risked their lives for Bangladesh in ,71

When the war broke out, Paul Connett and Ellen Connett had just returned from the US being involved in the Biafra campaign. While Paul Connett formed 'Action Bangladesh', Ellen Connett, who believed in direct action, co-founded "Operation Omega" with Roger Moody, an editor at Peace News. Members of 'Operation Omega', acquired an old Second World War ambulance and drove it to Bangladesh. Subsequently, she was arrested as she entered Bangladesh and imprisoned, only to be released by allied Bengali freedom fighters and Indian forces days before the final victory. While imprisoned, she discovered that she was pregnant and on returning to the UK gave birth to her son, naming him Peter William Mujib Connett.

The first time I came across the name Connett was in 2006 when we interviewed C A S Kabir, who mentioned, "So we participated, there were so many groups being formed, I also belonged to a group. My group was not Bengali people; my group was English people, plus other European people; there were two groups actually; one was called 'Operation Omega', and the other was called 'Action Bangladesh'. Paul Connett, a school teacher, led Action Bangladesh, and another leader was Marietta Procope, an Oxford graduate, and 'Operation Omega' was run by Ellen Connett and Roger Moody.

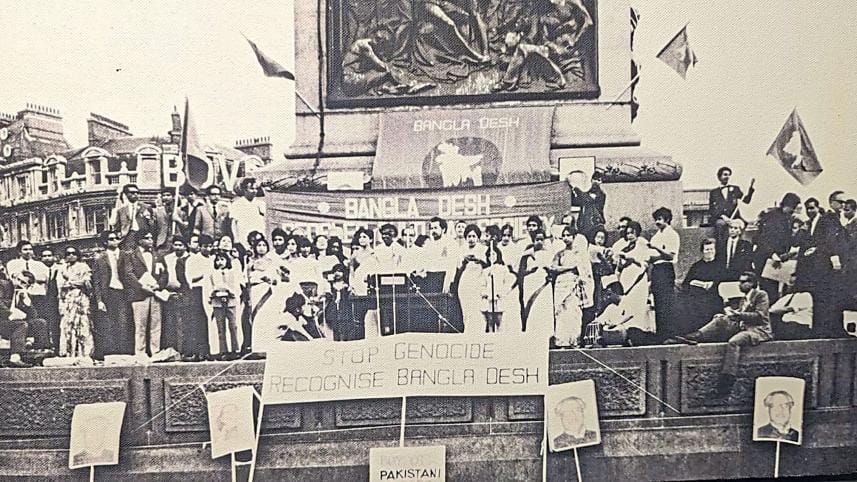

C A S Kabir recalls going to France to demonstrate outside the Paris Consortium to stop grants to the Pakistan government. With one Pakistani flag in hand, Paul Connett went in front of the Pakistan High Commission and said 'Joi Bangla'. The TV recorded that, and behind Paul Connett, Marietta Procope was there with another Bangladesh flag. So, two white persons were demonstrating against the military attack on the people of Bangladesh. One interviewer at that time from the television questioned Paul, 'You are a single person, and you are an Englishman; how can you free Bangladesh from the rule of the military junta?'. Paul, with his confidence at that time, declared, 'You watch and see what we can do,' later, he was able to draw 25,000 people to a demonstration in Trafalgar Square on 1 August 1971.

Then, in 2012, when the Bangladesh govt was looking for them, the Bangladesh High Commission in London contacted me to find him, which I was unable to do at the time.

I finally found them through an Indian documentary film-maker, Krishnendu Bose, and interviewed them on 16 Oct 2023 in their Preston Park, Brighton residence. Today, both Paul and Ellen are in their 80s but still are passionate about Bangladesh and their activism on several other human rights and environmental issues.

In 1971, Paul Connett, an Englishman and an American Ellen Connett, refused to sit quietly and worked to raise public awareness in London about the brutal killings which were going on in Bangladesh during the 1971 Liberation War. From 1968-70, they were in the US campaigning for Biafra, the breakaway region of Eastern Nigeria, but which was finally crushed by the Nigerian army in December 1969. This put Paul in quite a quandary in many respects. He had to return to England because he was on a student visa, which had been extended to allow his humanitarian work in Biafra. Paul had started a PhD in biochemistry at Cornell University before becoming caught up in the turmoil of the Vietnam peace movement and the McCarthy for President campaign. This in turn had led to his involvement in the Biafra campaign for which he became the President to the American Committee to Keep Biafra Alive. Now that Biafra had fallen, Paul's visa was no longer being extended and he had to abruptly leave his studies and humanitarian efforts behind to return to England.

Paul had initially gone to America to pursue his PhD studies at Cornell University in Ithaca, NY. His research director was Robert Holly, who later went on to win the Nobel Prize in biochemistry for his work on nucleic acids. While there, he became caught up in the activism sweeping college campuses at the time. The Vietnam Peace Movement and McCarthy's presidential campaign ignited a passion for activism within Paul. Campaigning for various causes became a part of his life. Paul met Ellen during his time as an activist around the Biafran cause. Ellen shared Paul's passion for the humanitarian crisis unfolding in Biafra. The two bonded over their shared desire and got married in March 1970.

The newlywed couple made their way back to Europe. It was a bittersweet time for Paul and Ellen. Their shared experience in Biafra had fostered a deep commitment to one another and to helping others. Paul and Ellen felt they had learned invaluable lessons from their time working on Biafra and were determined to keep the remarkable coalition they had built together. The alliance had brought together people across the ideological spectrum - from the far right to the far left - who cared more about human justice and lives than political divisions. This extraordinary mobilisation spanned the United States and much of Europe, with strong movements in England, Denmark, Germany, and France.

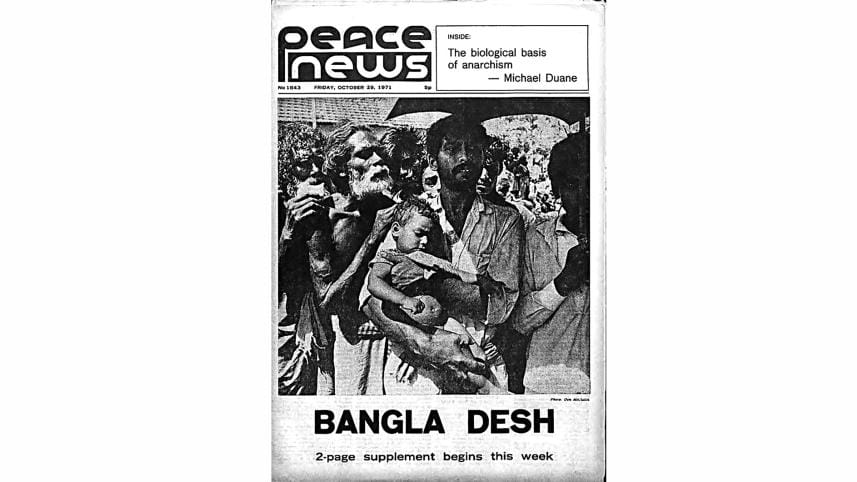

After returning to London, Paul and Ellen attended a meeting at Peace News headquarters where many of the people who had worked on the Biafra cause in London came together. Attendees included Members of Parliament like Michael Barnes, who had been vocal advocates for the Biafran people during the crisis. Everyone shared their grief and frustration over the international community's inadequate response to human rights abuses and mass starvation. However, there was also a sense of solidarity and commitment to continue fighting injustice wherever it occurred. Out of this meeting, the idea for a new organisation emerged - one that would draw on the diverse voices and skills of the extraordinary Biafra coalition they had assembled. Though that crisis had ended, its lessons would drive their future activism.

On hearing the news of genocide being carried out by the Pakistani military against the Bengalis, Paul Connett and Ellen Connett became proactive in fetching support for the oppressed Bengalis in East Pakistan and helped form two organisations in London named 'Action Bangladesh' and 'Operation Omega'. They recognised what was happening in Bangladesh was an eerie echo of what they had witnessed in Biafra - atrocities and oppression that the world seemed content to ignore. They organised numerous activities relating to the 'Stop Genocide;' and 'Recognise Bangladesh' campaigns. Other activists who worked with Paul and Ellen were Roger Moody, Ben Whitaker, Marietta Procope and several MPs. There were also many Bengali students living in London actively involved. Drawing on their coalition's diverse skills and passions, Action Bangladesh would advocate for the recognition of Bangladesh and pressure world leaders to intervene. It was born out of the ashes of Biafra but focused on a new mission. Paul and Ellen threw themselves into this new effort with zeal, determined not to let the momentum and solidarity of their extraordinary movement fade away.

At one of the planning meetings, Michael Barnes MP stated that the Bangladesh situation was even clearer than Biafra had been. He argued they should immediately call for recognising Bangladesh's independence. One of Action Bangladesh's first initiatives was running an advertisement in the Times of London aimed at Foreign Secretary Alec Douglas-Hume. It implored him not to dismiss the atrocities in Bangladesh as an "internal problem", stating that stopping genocide was everyone's problem. In just a few days, Paul and Ellen gathered influential voices to endorse the message, including former Nobel Peace Prize winner Philip Noel-Baker, writer Ben Whitaker, musicians like Yehudi Menuhin and many others.

Marietta Procope's home at 34 Stratford Villas, Camden, became the headquarters for Action Bangladesh as their campaign gained momentum. Every evening, Bengali students and activists would gather there to coordinate their efforts. Together, they would create posters for upcoming rallies, discuss strategies, and mobilise support. Marietta's tiny home was abuzz with passionate activity late into the night as this diverse group planned events to raise awareness about the atrocities happening in Bangladesh.

To form a public opinion to act against the Pakistani military and government and recognise Bangladesh, they organised the largest gathering in London's Trafalgar Square on 1 August 1971. It included the first British broadcast of the song 'Bangladesh' by George Harrison of the Beatles. Ravi Shankar had approached George Harrison to help with the Bengali's cause. In addition to this song, George helped organise a huge Maddison Square Garden concert.

Not surprisingly, the Pakistani government responded with a demonstration of its own a few weeks later. They brought in busloads of Pakistanis from the Midlands to have their own rally in Trafalgar Square. When Paul and others heard this would happen, they plotted a little counter-demonstration. Their budget was low, and they could not plan anything big. Instead, they had to be creative and produce something small but colourful enough to attract TV coverage. According to Paul, they hired army uniforms and dummy rifles to look like the Pakistani Army. They hired sound equipment and made some recordings of gunfire. They drove three carloads of made-up 'soldiers' into Grovesnor Square. They organised a simple demonstration of women and children in white saris marching in a circle in front of the American Embassy with placards protesting the US armaments being sent to Pakistan. The BBC were tipped off. The soldiers jumped out of the three cars, and with the sound of truck-blazing gunfire, they advanced on the peaceful demonstration. The women and children had little packets of stage blood in their hands, and as the guns blazed, they smeared these over their white saris and vests and collapsed to the ground, screaming with terror. Their little demonstration achieved equal time with the Pakistani demonstration, which would have cost thousands of pounds to organise, on the evening news!

While Action Bangladesh focused on traditional activism, like organising demonstrations and writing letters and petitions, Operation Omega took a more direct relief approach. Ellen helped to found this organisation. She felt compelled to provide on-the-ground assistance to the Bengali people suffering in the crisis. After witnessing Biafra, she was weary of activism from afar.

From page S4

Ellen was determined to help Bengalis directly through emergency relief efforts this time. As Paul coordinated the broader awareness-raising and advocacy work of Action Bangladesh, Ellen and Roger Moody had set up Operation Omega to send aid workers and supplies into Bangladesh. The two groups worked in parallel - Action Bangladesh pressuring world leaders to intervene, while Operation Omega attempted to provide desperately needed food, medical aid and support inside Bangladesh itself. It was a coordinated two-pronged effort, with Paul and Ellen tackling different but complementary missions. They drew on the same extraordinary coalition, leveraging everyone's skills and resources to raise awareness and send tangible assistance internally. Together, Action Bangladesh and Operation Omega formed a comprehensive campaign driven by a deep commitment to supporting the Bengali people in their time of crisis. Ellen said, 'Operation Omega was founded on the principle that we cannot let "political borders" stand in the way of aiding those in dire need. When the Bengali people were suffering atrocities and starvation, we refused to stand by because of political boundaries. If people needed help, we would find a way to provide it directly.' 'That's how our white WWII ambulance painted with the Omega symbol came to be. We would load up supplies and volunteers in this ambulance and attempted to drive across national borders to bring aid directly to the Bengali people. It was risky and illegal, but while we would not be deterred, we were stopped by the Pakistan army. While Paul coordinated protests and pressure to recognise Bangladesh politically, I focused on attempting to get immediate medical care, food and support to people internally,' added Ellen.

Operation Omega sent two volunteers to transport aid to Bangladesh – Freer Spreckley, blessed with the ability to get anything done, and a former policeman - on an arduous ambulance trip. They loaded a massive World War Two ambulance with medical supplies and set off from London to the Persian Gulf, where it was transported by ship to Mumbai. Then, it was driven from Mumbai to Calcutta. The treacherous journey took them across mountain ranges where they sometimes encountered bears. But they persevered, determined to bring desperately needed aid to Bangladesh. When they arrived in Calcutta, the local Gandhi Foundation supporters secured a small flat for Operation Omega's team to stay. Twelve volunteers crammed into this modest one-room apartment, preparing for risky border crossings into Bangladesh. To begin with the ambulance was driven openly up to the Pakistan border. But with the TV camera rolling, the Pakistani authorities refused it entry, and guards literally pushed it back into India. On the second try the Omega workers were detained but later released. No medical supplies had been delivered but a strong political message had been registered.

Paul arrived in Calcutta in September and they had spent a little time together there before he was approached by a Bengali doctor from Bangladesh requesting help to get medicines into Bangladesh. Paul along with Freer, a member of Operation Omega, were able to get a supply of medicines from one of the relief agencies helping the Bengali refugees in Calcutta. Paul and Freer accompanied 150 Mukti Bahini (Bengali freedom fighters) into Bangladesh. In their journey they were able to take photographs of the refugees exiting Bangladesh, "I saw eight-year-olds carrying four-year-olds," said Paul. "I saw a little girl, tears streaming down her face. She wanted to cry and stop, but she had to keep walking. We walked for two days and two nights and then we got on a boat and went for two more days and nights, and we reached a village, which in the monsoon rain had become an island. While there we witnessed smoke rising from a nearby village after being bombed by Pakistani planes. The next day we filmed the remains of the village on a camera loaned to us by UPITN. Later this footage was shown around the world. I captured these images." While Paul was away on this secret fact-finding mission miles within the embattled area, Ellen decided to make her sari-run across the border. Paul had made Ellen promise not to go into Bangladesh while he was gone. But Ellen thought it was safe. She felt the work needed to be done, and the others were busy with their own tasks. With another Omega worker, a 20-year-old South African student named Gordon Slavin, Ellen set off for a Catholic mission in Jessore 15 miles inside the Pakistani border. She described, 'It was the monsoon season, so we went by boat over flooded rivers. Travelling at night, it took us nine hours to reach the mission. The priests took us in, and everything seemed safe.' But by the following day, 30 armed West Pakistani soldiers greeted them as they stepped out the mission door. She said, 'An informer must have seen us. We were arrested, tried and sentenced. Gordon and I just resigned to spending the next two years in a jail in Jessore. Their crime was illegally crossing a border to bring 200 saris to stranded Bengali villagers. When Ellen was asked in a televised interview, 'Didn't you know what you did was illegal?'. Ellen said, 'Of course I did. But I don't think you need permission to help someone who's suffering?'

Paul heard over the Pakistan radio that two Operation Omega workers were arrested, and one of them was a woman. He immediately knew who she was. With that, he returned to Calcutta, then England and then to the United States to work on her release. "I was worried and angry at the same time," Among other things, it meant that he would not be able to speak out on what I had seen in Bangladesh as he had hoped. Until Ellen was released, I could not speak out or campaign without fear of reprisal on her. Fortunately, we only had to wait two months – but it was a very worrying two months." On 4 December, Ellen Connett and Gordon Slavin were released and escorted back into Calcutta by an Indian Major. On being released from the Pakistani prison, she recalled, 'I can just remember the shouts of happiness the day the guerrillas took Jessore and liberated our prison. 'Joi Bangla!' they kept yelling. Victory to Bengal! The week before India intervened, India's fighter jets roared over the Jessore prison as a show of force. The deafening noise terrified us prisoners as we feared they were attacking. We all screamed, convinced our end was near. The Indian military was sending a clear warning for the Pakistani forces to withdraw. But to us trapped there, it felt like being caught in the crossfire. I was certain I would die and never see my newborn again. But the next morning, I woke unusually early to sunlight and a beautiful sound - people chanting "Joi Bangla" outside the prison walls. India had launched a full intervention overnight. Pakistani guards had fled, leaving us unharmed. The chanting signalled freedom was imminent. After months of imprisonment, suddenly, we were being liberated! Stepping outside the prison at last, smoke was still rising from targeted buildings. But the chants of "Joi Bangla" echoed all around. After everything, we were alive to see this moment. I said my own prayer of thanks as we marched into that smoky dawn, the red and green of the new Bangladesh flag flying proudly ahead. What had seemed impossible was now glorious. These people have suffered enough. They deserve some joy. When they returned to New York, she told Paul she was pregnant. While Ellen was imprisoned in Bangladesh for her humanitarian work with Operation Omega, she discovered she was pregnant. The news came as a shock under such dire circumstances. Alone in her cell, thoughts of the child she was now carrying gave her strength to endure. For Paul and Ellen, the pregnancy and birth under such traumatic conditions were almost too much to bear. But amidst the grief and trauma, there was also joy - they were now parents with a new life that symbolised hope after months of darkness. As they processed the complex emotions, their commitment to one another and to justice deepened. Bringing their child into the world had changed everything. He was the legacy of their love and their still unflinching dedication to humanitarian ideals, even in the face of unthinkable cruelty. They vowed to honour his birth by continuing to stand up for human rights, no matter the cost They called the new born Peter William Mujib, named after Sheikh Mujib.

This is how the New York Times reported on 14 December 1971:

A 28‐year‐old American woman held in a Pakistani prison for two months until she was freed last week by Bengali rebels returned to the United States last night for a reunion with her husband and parents. Mrs. Ellen Connett, of Dumont, N.J., arrived on an Air India flight from Calcutta shortly before 11:30 P.M. at Kennedy Airport. "I've gone through very little compared to the suffering, to the immense suffering, of the people of Bangle. Desh," Mrs. Connett said. Mrs. Connett, who worked for a relief organization known as Omega, was arrested in small village in East Pakistan early in October for illegally crossing the border with relief supplies for Bengali natives.

Finally arriving back in America, Ellen braced herself to face her parents for the first time since her hurried wedding in March 1970. Despite letters, Ellen's parents had no real understanding of the dangerous mission she had thrown herself into. All they knew was that their daughter had abruptly eloped to follow a cause across the world.

Talking to Daily Star, the couple said the world should not forget about Bangladesh and the genocide that took place in 1971, 'We should never forget Bangladesh reminding the world about the war, sacrifice of the people, and how brutal humans can be, not to mention how beautiful some of them can be.'

Commenting on Bangladesh's struggle, Paul said, looking back on Bangladesh's fight for independence, there were clear genocidal implications in what West Pakistan tried to do. They sought to eliminate Bengali culture, starting with banning the Bengali language. Depriving a people of their native language is a stepping stone to genocide - an attempt to erase their cultural identity. The world was focused on the mass killings and pragmatic challenges of governing East and West Pakistan, separated by over a thousand miles. But this cultural erasure was a grave threat as well. As Ellen learned more about Bengal's rich literary tradition, she gained a deeper understanding of how much was at stake. The Bengalis were fiercely proud of their language, art and culture. Oppressing these integral parts of their identity was another form of violence.

Finally, both felt Bangladesh has a significant role in upholding secularism, women's empowerment, and its beauty and music. Paul is a fan of Tagore music. They also praised the Bangladesh government for giving shelter to the Rohingya refugees and becoming a host country the way India hosted over 11 million Bengali refugees during the war in 1971

In 2013, the Connetts were honoured for their contribution back in 1971 by the Bangladesh government as "Friends of Liberation War."

Ansar Ahmed Ullah is a contributor to The Daily Star.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments