Creating our own language in film

FOR a director, completely objective analysis of cinema is difficult. So, I was in a dilemma when I sat down to write this piece for The Daily Star about Bangladeshi cinema, its language, the challenges and potentials. But then, aren't we all subjective in the end? So, let me make it simple and just share what I feel to be true in my journey as a Bangladeshi director.

We often talk about “Bangladeshi cinema,” “Iranian cinema,” “Chinese cinema,” etc. What do we mean by such umbrella terms? I remember when I made telefilms and series for television, people would often tell me, “Oh, I started watching that telefilm midway through, and I instantly realised it was you who directed it.” I have heard the same thing even when I made a commercial, which comes without credits. How do people know which ones I made? These questions have led me to believe that what people actually recognise is my “language”—the language of an artist that distinguishes an Abbas Kiarostami film from other films, a Humayun Ahmed book from other books, an Al Mahmud poem from other poems.

Each artist has a distinctive language that reflects their nature, philosophy and personality. Thus, each work of art is personal and has the artist's “personal language” embedded in it. But can there be a film language, or a poetic language, for example, that can represent an entire nation? I can't explain it based on any theory, but I have this feeling that when people say they can recognise an Iranian film, or an Indian film, or a Korean film—just by watching it—they don't just recognise the distinct faces of the characters, the language, and the locations; there is an ingrained collective language that binds them together and makes a film uniquely identifiable. Which is why, the films by Abbas Kiarostami and Asghar Farhadi, despite the two directors being polar opposites in terms of style, are uniquely Iranian.

Did Bangladeshi cinema attain any such distinctiveness? Going by the analyses of film critics and discussions on global cinematic trends, it appears Bangladesh is yet to attain a distinct character, although one could sense the presence of a distinct cinematic language in certain Bangladeshi films of the last 10-15 years. But the number of films like this is too small to make a wave.

Since I started making movies, I have said this over and over again: The main reason as to why we haven't attained such distinctiveness is that we have overshadowed our cinema industry with an Indian flavour. In the name of so-called mainstream movies, we have (and still are) arbitrarily duplicated movies that were originally made in Kolkata, Mumbai and Tamil Nadu. If we did not completely copy an Indian film, we at least adhered to the structure and language typically seen in Indian cinema. On the other hand, while making art house films, we followed Kolkata. In the process, our cinema has become a copycat of Indian cinema.

Human beings inherit commonness, but they also possess a uniqueness based on their origin, ethnicity and background. As people are different, so are their habits, reactions, stories. Therefore, our cinemas ought to be distinct if we make cinemas by honestly portraying ourselves.

In a story, two factors shape its characteristics: its characters and the storyteller. In my opinion, the characters are the most important part of a cinema. It is the habit, temperament, mood of the characters—and the emotional journey they are going through—that determine the cinematographic language, acting pattern and rhythm of a story.

Let me give an example. Television and Doob are two of my films. They are different from each other in terms of the cinematographic language, mainly because of the two films' distinctive characters. Doob was all about a family. They belong to the elite class of society and are very introspective. After having divorced, the couple—the parents—become reserved and go into their respective shells. They refuse to express their inner emotions, creating a facade for the outside world. Each becomes like a mountain river, so detached from each other that they make conversations in silence.

To tell the stories of these characters, I embraced a quiet and unhurried cinematic language. Now, if I impose the same language on the emotionally eccentric and colourful characters of Television, it would be a disaster. The same would happen if I foist Television's visual style upon Doob. As it turns out, once the emotional landscape of characters is grasped, the film becomes unique, automatically.

Now enters the storyteller. Let us suppose that two individuals go to the stadium to enjoy an Abahani-Mohammedan match. After returning home, they are asked to discuss their experiences. They would tell two completely different stories. One might find the peddler at the stadium very fascinating. The other story might revolve around a beautiful girl. It is entirely possible because the two storytellers are two different beings. Their personalities, interests and philosophy are such that they would tell a different tale about the same game. This is the role of the storyteller. Also, that is precisely why Doob and Television carry the signature of the same director despite having differences in terms of their visual styles.

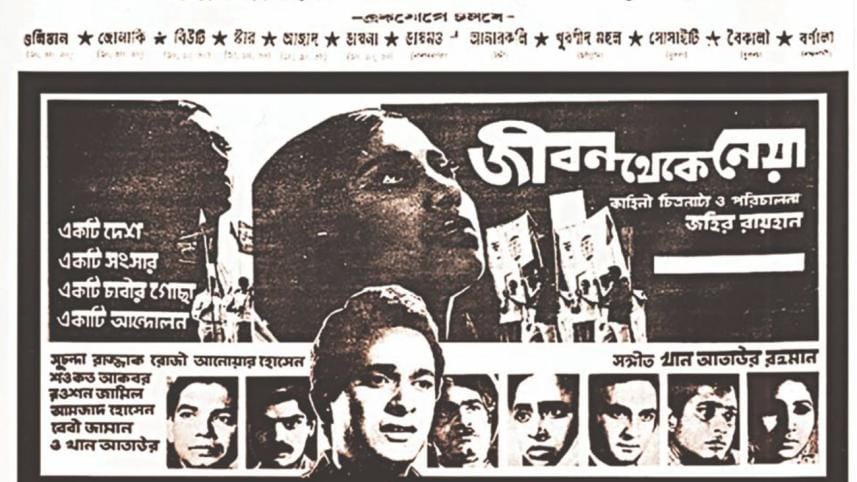

It is high time for our cinema to attain its own distinct identity. All one has to do is portray the stories of our own people and emotions. With all the limitations and challenges, Zahir Raihan, Masihuddin Shaker, Azizur Rahman, Tareque Masud and Morshedul Alam have told their stories. In this era of technological advancement, the global cinematic world is available to everyone. Now is the time to experiment and make films of our own—cinema which reflects our uniqueness.

The potential challenges, it seems, are the same ones faced by filmmakers all across the globe. Aside from convenience, technology has brought some challenges, too, with image bombardment being the primary one. We are accustomed to seeing plenty of images in a short span of time. As a result, it is more difficult to connect with the audience just with beautiful imagery. The eyes might find them beautiful, but it is harder to impress the mind. When a viewer goes home after having watched a movie and discusses it at the dinner table, or thinks about the characters and debates about it in social gatherings for days, the art survives and becomes a part of the evolution of the society. We do not come across such movies so often nowadays. I do not know why, and I would leave it for social scientists and researchers to find out. I can only say that our changed lifestyle may have something to do with it.

I look at the small device in my hand. I know what blessings this tiny device has brought. At the same time, I wonder, has it changed me? Have I become restless? When we browse Facebook, do we stay with a particular post on our newsfeed? Wouldn't we rather scroll down endlessly? Does this new habit make me agitated?

Am I not constantly looking for stories and sounds? When the newsfeed goes quiet, why do my eyes and ears become unstable?

When I reflect on these questions, I feel that our psychology is undergoing major changes. This change influences our cinema. Perhaps, this is why mainstream films always have to have something constantly happening. Even when nothing happens in the story, a kind of restlessness is applied to the editing. There has to be some constant sound effects, music or buzz. They can't imagine the notion of an absence of music, dialogue or sound effect.

Is this an outcome of the changes in our habit? I don't know, I really don't, but something that I do know is that in old classic studio films, we used to see lots of arresting silent moments. It seems those days are gone. We are now afraid to have silence in films because we are afraid the audience in this “age of scrolling” may get bored and want to scroll down and move on to the next episode. We have now entered an age of restlessness. We have created an age of the visually spectacular in mainstream films. We want to dazzle the eyes. But a good film is not supposed to end its journey merely after it has been seen. It is supposed to go beyond, reach the heart, linger there for a longer period of time, and continue a dialogue. We will have to make cinemas that go beyond our eyes to reach our mind. This is the toughest challenge of filmmakers of our age.

And, the last challenge is to overcome the quick reviews and reactions that flood social media as early as after the first show. It is only natural that the audience will express their reactions, say good or bad things about a film. It happened in the past, too. The difference, however, is that the reactions did not spread so quickly. As a result, one used to watch the film on their own and take a side only after having watched it. It was after watching the film one could let others know about the film and influence that person's decision on whether or not to watch it. These days, however, word of mouth spreads so quickly that many people form their decisions about watching (or not watching) a film based on what others have to say about it. In other words, the early viewers make the decision for most potential viewers. In my opinion, it is not helpful for new films or new language, because these films need some time to be properly understood.

One of my films, Bachelor, was initially watched by an urban audience. Some outright rejected it, while others had the opposite reaction. But, as the film grew older over time, it eventually found a warm place in the public mind. Every new experiment or innovation takes a certain period of time for people to adapt to it. As poet Binoy Majumdar once said, “For cream to rise to the top of milk, it takes a bit of time.”

Mostofa Sarwar Farooki is a film director, producer and screenwriter.

This article was translated by Badiuzzaman Bay and Nazmul Ahasan.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments