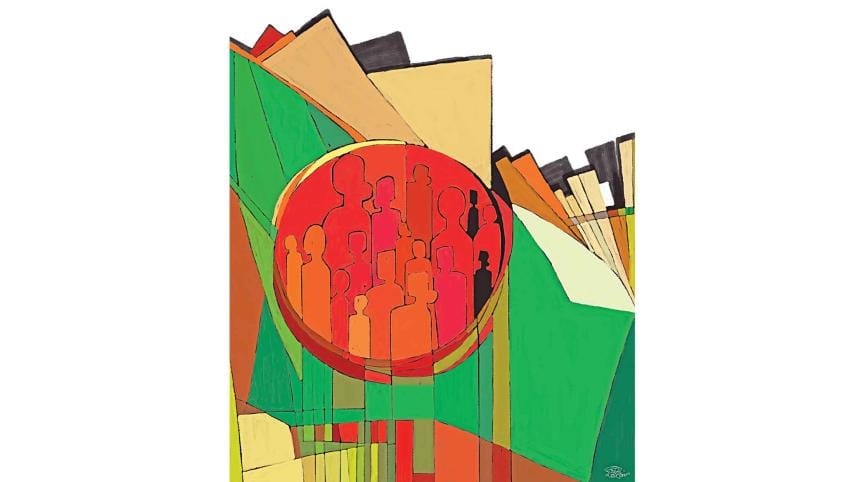

Towards multiplex horizons of nationalism

As Bangladesh steps into 50, the people of this country can rightfully be proud of a rich heritage of her story—a story of struggles, movements for emancipation, autonomy, liberation and independence. For many of us who have experienced 1971, it is an intensely personal, emotional and political moment in our lives. I consciously use the word "moment", as time had frozen for many of us.

Returning to a free, independent Bangladesh in December 1973 after being interned in Pakistani camps for over two years, Bangladesh to me epitomised the land of freedom, a land where I will not be held behind barbed wires with electricity passing through them from time to time, a land where I will be free to receive my education, as my school days came to an abrupt end due to our internment. My days in the camps were in essence a longing within me to come back to my own land, Bangladesh. For me, home and homeland acquired a meaning of freedom—freedom from fear, freedom to speak out, a sense of being at home where one can be ones' very own self. This selfhood held varied faces and layers of identity and memories. In my imagination, I had created my land of freedom and independence—Bangladesh. I distinctly remember that the nationalist songs that we could hear on radio in a programme broadcasted by Bangladesh Betar, Probashe Bangali, made me cry so many times. My generation has all the reasons to be emotional and proud of 1971. We witnessed the birth of a country out of a genocide.

A genocide is not only about human persecution, torture and miseries, but it has a history behind its making. Institutions, policies and languages are constructed to carry out this crime against humanity. One of the worst genocides in history took place in 1971, where religion was used as a weapon. The state of Pakistan was supposedly created as a homeland for the Muslims, based on the two-nation theory. The Bengalis were considered as "impure", "lesser Muslims", or "Hindus".

In the making of a genocidal discourse, the process of "othering" is critical. The labelling began right after the creation of Pakistan in August 1947. In March 1948, Mohammad Ali Jinnah, the Father of Pakistan, declared in the premises of Dhaka University that Urdu and only Urdu shall be the state language of Pakistan. The Central Minister for Education in Pakistan equated Bengali alphabets with Hindu gods and goddesses and suggested that Bangla be written in Arabic script; Bangla script written in Devanagari script was equated with Hinduism. The playing of Rabindra Sangeet was banned. The Bengalis took these as direct assaults on their culture, and the seeds of Bengali nationalism were sown through the Language Movement. Political and economic deprivations and exploitations of the Bengalis in East Pakistan by the Pakistani ruling elite constituted an integral part of this process. It was a politics of othering, alienation and exclusion in the name of nation building.

Interestingly, despite the nationalist movements waged by most of the post-colonial states for liberation and independence, they failed to liberate themselves from the western understanding of nation and nationalism. Consequently, ethnic and sectarian conflicts emerged as ethnic boundaries did not necessarily match the political boundaries, but the quest was to carve out a "nation" out of a people. India has witnessed ethnic and sectarian conflicts in North-east India and Punjab, and Kashmir remains an ongoing conflict. Sri Lanka faced a bloody civil war between its Sinhala and Tamil population. In neighbouring Myanmar, the genocide committed by the Myanmar state has led to the exodus of 1.1 million Rohingya refugees into Bangladesh. This politics is garbed in the name of nation, nationalism and indeed, national security.

Bangladesh, which can boast of a homogenous population of 98 percent constituting of ethnic Bengalis, has had its share of ethnic conflict. The Hill people of Chittagong Hill Tracts (CHT) failed to identify themselves with either Bengali or Bangladeshi models of nationhood that the country has experimented with. The consequence was over two and a half decades of insurgency in the CHT that ended with the signing of the CHT Accord on December 2, 1997. However, the accord has not been fully implemented, largely due to built-in limitations within the accord and lack of political will of the state. Peace remains an unfulfilled dream in the region. The removal of secularism as one of the state principles in 1977 and the later adoption of Islam as the state religion in 1988 has turned people of religions other than Islam into religious minorities. Bangladesh today has ethnic minorities and religious minorities. Although in 2010 secularism was reinstated in the Constitution, Islam remains the state religion.

The majority minority dichotomy, although unfortunate, is not surprising. It is inextricably linked to majoritarian democracy, which is practiced in Bangladesh. It results in political parties leaning towards the majority for electoral politics at the cost of democracy, democratisation, governance and institutionalisation of institutions. Major political parties have adopted uni-versions of nationalism and nation. Yet people have multiple identities, which cuts across religious, ethnic, linguistic, gender and economic lines. With the surge of technology, identities may be formed along digital lines in future.

Points to ponder are, if our politics and politicians are listening to the many voices that were and are there; are they listening to the aspirations of the future? Even a look at our culture and history tells us a different story. Rabindranath Tagore's Amar Shonar Bangla, Ami Tomae Bhalobashi, (my golden Bengal, I love you), which was adopted as our national anthem, had provided solace and inspiration to the people of this land in 1971 and continues to inspire us through all adversities. Tagore celebrated the diversity of human races for social harmony. He was a strong critique of "nation" and nationalism—according to him, nation and nationalism robs the people of its plurality and organises them mechanically; he looked at Indian history as one of social life and attainment of spiritual ideals.

Nazrul, the "national" poet of Bangladesh, sang songs of equality, harmony and unity. He wrote in his Sammobadi—Gahi Shammer gaan, jekhane ashia ek hoye geche shob badha baebodhan, jekhane misheche Hindu-Buddho-Muslim-Christian… ei hridoyer cheye boro kono mondir-Kabah nai (sing the song of equality, where all the obstacles and differences have merged, where Hindu, Buddhist, Muslim, Christian have come together… there is no greater temple or Kabah than this heart).

Our famous nationalist song by Gauri Prasanna Mazumder describes the beauty of this land through different gazes—Bishwo Kobir Sonar Bangla, Nazruler Bangladesh, Jibonanader Ruposhi Bangla, Ruper je tar nei ko shesh, Bangladesh (Bishwo poet's [Tagore] golden Bengal, Nazrul's Bangladesh, Jibananda's beautiful Bengal; there is no end to the beauty of Bangladesh).

The song speaks of the multiversity of gazes and languages through which a land and its people may be seen and described; or more importantly, how the people want to be seen and be described. Let Bangladesh discover its glory in its heritage, its pride in the multiversity of its cultures and people. Let the posterity fly high and touch the multiplexes of nationalism that transcends the western understanding of nation with its many exclusions and move towards an inclusiveness that captures the imagination of the lived lives of its people; so that 50 years from now and at the 100 years of Bangladesh, someone will look back and reflect on the proud journey of Bangladesh as a land of multiplex.

Dr Amena Mohsin is Professor of International Relations at the University of Dhaka.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments