A bloody war and how I witnessed it

When I think of the bloody birth of our nation, I feel the weight of history on my shoulders. It’s overwhelming to think of how we had reached that moment, the whole gamut of historical changes that this land has gone through, with its complex interweaving of political and social influences, cultures, events and political intrigues. Every chapter of that history tells us an amazing story, revealing more and more of the historical backdrop to our present times. A period of a thousand years or so in the life of a nation may be hard to imagine. Perhaps it is easier to imagine one’s grandmother living to be 100-years-old.

What we now call Bangladesh has never been home to a single people. There have been invasions and settlements over the thousand years, people migrating beyond boundaries and across the land, communities breaking up and forming again, power changing hands, and new identities being created as the wheels of history rolled relentlessly.

One may recall that in the not-so-distant past, English-speaking people from Great Britain came to India and Bangladesh, ruling or misruling our people for nearly two hundred years. Those of us who are now old and frail witnessed the fall of that empire. Of course, the British also had to suffer colonial subjugation by the Romans for a much longer time. The history of Bangladesh, now inching closer to the golden jubilee of its birth, is fairly short compared to the times we had left behind, before the 1971 war of liberation, before the Partition, before the English arrived. Yet this history is one that began with a glorious—and beautiful—uprising by the people, inspired by a socialist vision to build a fair, just society and a country that they could call their own.

But before the war broke out, did the political class know about the impending disaster? Could they foresee it? There are some questions about the political wisdom of our leaders at the forefront of our struggle for independence, which still remain unanswered. However, it is also my considered opinion that the ruling class in Pakistan’s west wing, faced with the growing Bengali demand for regional autonomy and power sharing, must have chalked out their sinister plan for a military solution to these issues before the elections of 1970.

But the civil-military bureaucracy led by General Yahya Khan and the politically overambitious leader of Pakistan Peoples Party, Zulfikar Ali Bhutto, failed to correctly assess the Bengali determination to go all out for Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman’s Awami League and his six-point demand for extensive autonomy. They also misjudged the prevailing political situation in East Pakistan and the mental make-up of the Bengalis and their thought process. Bhutto, with his unquenchable thirst for power, was even ready to sacrifice national interests to grab power. Some analysts say that it was his ambition to get power that led to the political catastrophe and broke the two wings of Pakistan, creating Bangladesh.

In the 1970 elections, Awami League under Sheikh Mujib won a landslide victory in both the national parliament and the East Pakistan Provincial Assembly, while in West Pakistan, Zulfiqar Ali Bhutto’s Peoples Party won. But since East Pakistan had the majority seats in Pakistan, it was natural that Sheikh Mujib would become the next prime minister of the country. Besides, Yahya Khan also declared Sheikh Mujib the country’s next prime minister. But Bhutto as the winner in the west wing claimed his part in power. He claimed that the majority in West Pakistan didn’t vote him to sit in the opposition bench in parliament. And this is where the line of separation between the two naturally separate wings of Pakistan was drawn.

I had worked with the Associated Press of Pakistan (APP), Pakistan’s national news agency, for 12 long years and resigned from it in February 1971. I was officially released a month later, on March 24, just on the eve of the military crackdown on Bengalis. As a journalist of some standing, I had the opportunity to witness first-hand how the situation gradually deteriorated to the point that it finally did, leading to the bloody war.

I remember in the closing years of Pakistan, I had often been covering domestic and foreign visits of General Ayub Khan, General Yahya Khan and Bhutto, Ayub’s foreign minister in the early 60s. In the course of those visits with the Pakistani dignitaries—mostly Panjabi and other Urdu-speaking high officials like ministers and foreign secretaries, Pakistan’s ambassadors in foreign capitals, etc.—I covered official conferences, meetings and news conferences. Some of those officials and diplomats and my fellow Urdu-speaking journalists would often raise the question of Pakistan’s east-west relations, and occasionally someone among them would raise the question of the possibility of a secession of the east wing.

I recall that once in Rabat, Morocco, sometime in 1969, during the first Islamic summit of the Muslim heads of state, a non-Bengali journalist at an informal gathering asked a senior Pakistani diplomat, Agha Shahi, about how they in the central government would react to any possible move by the east-wing leaders for secession. The diplomat, with a smile, replied: “If the Bengalis want to secede, I think the central government or the people of West Pakistan may not have any objection.” My journalist friend looked at me and asked for my reaction. In reply, I told the small crowd of diplomats and officials: “Since we Bengalis are in a majority in Pakistan, the question of secession from our side does not arise. Pakistan belongs to us in the East no less than you living in the West (Pakistan).” To me, it appeared they had nothing more to add after what I had said. But it was also clear from the diplomat’s comments that the Pakistani leadership was also aware of the possibility of a Bengali move for secession.

About a year later, in 1970, as a member of the press corps, I was covering the election campaign of Bangabandhu and Awami League. So during a campaign trip, I told Bangabandhu about my encounter with the west-wing diplomats on the question of secession by us vs by them, the non-Bengalis. The great Bengali leader spoke in the same vein, saying, “In Pakistan, we Bengalis are the majority, so why should we go for secession?”

But things quickly deteriorated in the ensuing months, which makes me think that great events in history are sometimes not the result of a well-crafted plan but rather a spontaneous action prompted by the prevailing situation on the ground. For us, the background for our action—going all out against the Pakistani leadership for independence—was long in the making. And when the time finally came, we fought the ruthless military for nine gruelling months. People, old and young, joined the war and fought back against their brutalities with everything that they had. Many of them cherished, never to be mentioned in the history book for their sacrifices. Many were scarred for life. In the end, the victory was ours.

Nearly five decades have passed since then. Today I find it ironic that we often talk about the sacrifices of those people—people at the front of the war and people who supported them in all possible ways from the background—and we remember them with respect. We claim that we will never forget their sacrifices. But our pledges remain trapped in flowery language and elaborate but uninspired gestures. I think respecting someone’s sacrifices means carrying out their work, doing what they made their sacrifices for. But are we doing it? I look around, I see all the injustices and crimes and exploitations around, and I wonder how far off that hallowed path (and pledge) we have veered over the last few decades. Those people gave their life so we, all of us as a society, could live in peace and happiness. It pains me to say that their dream remains unfulfilled.

I think it is time we walked the talk on our pledges to uplift the spirit of the liberation war and strived to create a just, fair society that we can be really proud of. Only through that can we honour our pledges and the memory of our freedom fighters.

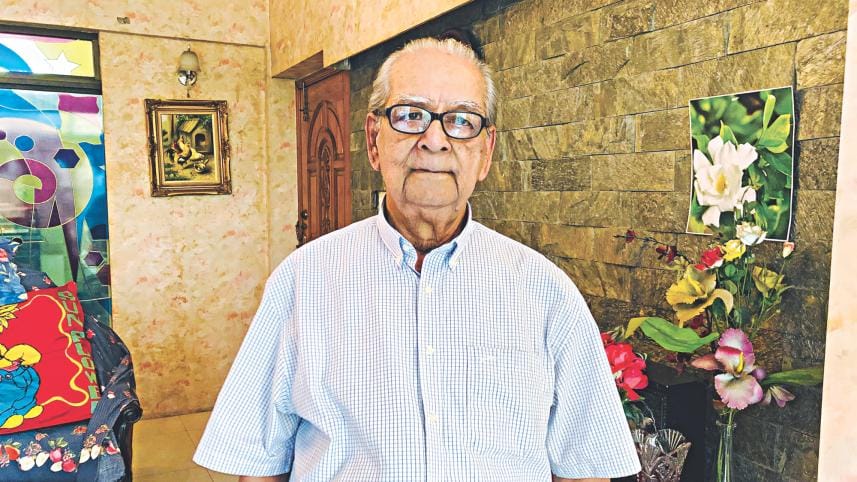

Amanullah is a former Chief Editor of Bangladesh Sangbad Sangstha (BSS) and former Director General of Press Institute of Bangladesh (PIB). He covered the election campaign of Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman during the 1970 elections. He also covered the Agartala Conspiracy Case and is set to publish a book on the case and its trial early next year.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments