Method in Madness

Bangladesh paid a heavy price for its freedom. There are few nations which have to make such sacrifice for its freedom. India has a long history of struggle against British colonial rule, on many occasions the conflict became brutal and bloody, but the independence came in 1947 as a negotiated settlement, being a peaceful handover of power. There are other countries where people have taken up arms to achieve their freedom. The war of liberation was bloody in countries like Algeria or in Angola, but there was no widespread and systematic attack against civilian populations like the one that Bangladesh experienced in 1971.

The very nature of the state of Pakistan made Bangladesh's struggle unique in character and many in the West failed to take note of this uniqueness. Pakistan was a country formed with two wings separated by more than thousand miles of physical distance. There was no such country before and one can be assured that there will not be any such country in the future. The only bond between the two parts of Pakistan was that of Islam, the religion of majority of the population. The founding fathers, in conjunction with the British colonial rulers, aspired to build a state based exclusively on religious identity, over and above the national entity.

In order to make possible the impossibility they had to destroy the linguistic-cultural identity to create a new nationhood of Pakistan. This mission reflected the concept of “imagined community” at its extreme. This view is aligned with Benedict Anderson's theory regarding nations as what people imagine of themselves, or what they can be made to imagine. On the other hand, there are long historical, geographical and cultural processes which create the bond of nationhood, a nation not imagined, but rooted, inherited, re-discovered. If Pakistani nationhood is an imagined phenomenon, Bangali nationalism is an amalgamation of traits that are real. A popular slogan born out of the struggle for Bangladesh reflected this reality – Tomar Amar Thikana, Padma, Meghna, Jamuna. Rivers are where we belong. Such a national identity is real, reflects physical, historical, cultural entity consisting of tangible as well as intangible heritage.

The physical distance between the two parts of Pakistan was great but greater was the cultural, national, historical and social differences. In such case the State recognising diversity of its population could hope for a chance to be functional, but the state of Pakistan based on so-called “Two-Nation” theory recognised the Muslims of India as a 'religio-nation'. The centralised state had little chance to be functional and Pakistan as a nation-state tried to overcome its inherent contradictions not by compromise but by coercion.

The first coercive step of the state was the denial of right of the language of majority of the population when Urdu was declared the state language with an inherent and false claim that this language is more Islamic than others. In face of growing opposition to this project the rulers resorted to the use of force to deny the national and democratic rights. This trend culminated in the attempt to achieve the solution of political problems with brute military might unleashed on 25 March 1971 with widespread and systematic attack against the Bangali people upholding their national rights.

This attack culminated in Genocide and Crimes against Humanity. This ideology of the perpetrator produces a mindset based on prejudice and the prejudiced mind creates the dehumanised entity which undertakes a mission to eliminate the others. Ideology of prejudice and hatred against Bengali people branded them as enemy of Islam, lackey of the Hindus, agents of India, etc. Such classifications lead to targeted attacks against the national group with an aim to reorganise the nation based on the ideology of the perpetrators.

How the Pakistani military rulers depicted the Bangali people can be an interesting exercise by itself and helps one to understand the journey from ideology to action to exterminate. General Ayub Khan in his autobiography “Friends not Master” wrote. “Bengalis have all the inhabitations of lower trodden races and have not yet found it possible to adjust psychologically to the requirements of new-born freedom.” Major General Rao Farman Ali in the very beginning of his book “How Pakistan Got Divided” wrote, “Bengali Babu, Bengali Jadoo and Bhooka Bengali : these three pronouncements were what we had heard about Bengal in our childhood.” The discussion in the Dhaka Cantonment following the brutal attack on 25 March, 1971 was reported by Brigadier A R Siddiqi in his book “East Pakistan: The Endgame”. He wrote about the staff conference held on March 27 where everybody exuded confidence and looked fully satisfied with the progress of the military operations. Thus spoke Brigadier Jeelani in the meeting: “Urdu script must replace the Bangla script which was the same as the Hindi script and all Hindu features of the Bengali culture should be erased. There was nothing wrong with the Bangali masses as such: they were a simple God-fearing people. It was the educated middle class – the teachers, lawyers, intellectuals, (mostly Hindus) who are behind all the un-Islamic ideas and motivation amongst the youth.” The Pakistani Brigadier not only singled out the intellectuals and Hindus but attacked the Bangali nation as well when he said, “Too much freedom was not good for the Bengalis. They did not have it for centuries and were like to make a mess of it when they did.”

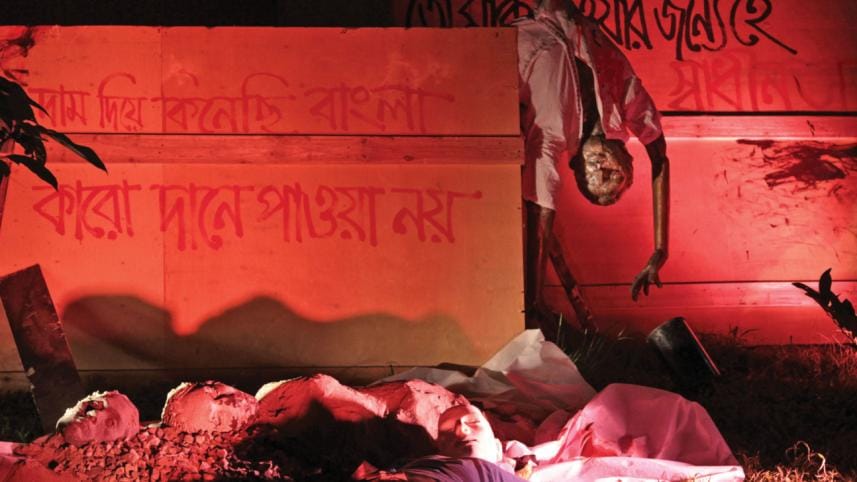

Such a mindset took concrete form in the military attack, the plan of which known as “Operation Searchlight” reflected that attitude. In the plan among the targets, mention has been made of “extremists amongst teaching staff, cultural organizations”. Tasks included such missions as, “Dacca University will have to be occupied and searched.” As a result the killing spree in the Kalratri targeted annihilation of intellectuals like Professor G. C. Dev, Jyotirmoy Guha Thakurta, Dr. Moniruzzaman and others. But the most brutal and well-organised killing of intellectuals was organised on 14 December, 1971 just hours before the surrender of the Pak Army. The intellectuals were picked up from their home, taken blindfolded to Mohammadpur Physical Training Centre, brutally tortured and subsequently killed and dumped at the Rayer Bazar brickfield in the most barbaric way. Such brutality is difficult to understand but need to be studied deeply.

Daniel Jonah Goldhagen in his book, “Worse than War” has identified the phenomenon of “excess cruelty” in the acts of extermination. Such barbarity is not necessary to kill a person but has become a common feature in the acts of elimination. He highlighted the importance of studying cruelty and wrote, “In eliminationist and exterminationist assaults, 'excess cruelty' is commonplace and it varies widely from one eliminationist assault to the next. Both these aspects, and their sources, are significant and need to be explored if we are to understand our times' mass murders and eliminations.”

In his effort to understand the phenomenon he further wrote, “There are different kinds of 'excess cruelty. A two-dimensional matrix, with one dimension being whether the cruelty is ordered from above and the other being whether it is individually or collectively performed, specifies four kinds of excess cruelty.” In case of ordered from above he identified both collective and individual role. In case of those not ordered from above he found group performance and individual initiative. Such analysis can be of help to us to understand the killing of intellectuals and the 'excess cruelty' as component of the operation.

International Crimes Tribunal of Bangladesh, while adjucating the cases of individuals accused of crimes of genocide and crimes against humanity, has to deal with the killing of the intellectuals in multiplicity of cases. The observations and verdict in different cases can be studied together to get better understanding of the killing of intellectuals. In the case of Chief Prosecutor vs. Ali Ahsan Mujahid the Tribunal took cognizance of intellectual killing not as 'Murder' but as 'Extermination'. It referred to ICTR Appeal Chamber verdict that, “The Trial Chamber followed Akayesu Trial Judgement in defining extermination as a crime which by its very nature is directed against a group of individuals. Extermination differs from murder in that it requires an element of mass destruction, which is not required for murder.” Interestingly ICT-BD noted, “It is now settled that in order to give practical meaning to the offence of 'extermination', as distinct from 'murder', there must in fact be a large number of killings, and the attack must be directed against a 'group'. In the case in hand it has been proved that the large number of killing under charge No.6 was aimed to annihilate the 'Bengali intellectual group', a part of the national group.”

ICT-BD in its various judgments has elaborated legal concepts based on the fundamentals of law and the context of the crime. The Tribunal rightly considered the intellectuals as part of the 'national group'. This recognises destruction of the nation as the aim of the perpetrators and helps to understand broader context of the crimes. Such exterminationist acts fall under the category of crimes against humanity but also reflect the intent to destroy a part of the national group which can be categorised as genocidal crime.

Another interesting development in the aforementioned case is the incorporation of the concept of Joint Criminal Enterprise (JCE) which is a later development in the International Criminal Law, not to be found in the statute. It has not been categorised in the statute of Bangladesh Act, nor could this be found in ICTY or ICTR statute but evolved through judicial pronouncements. On the basis of such observation the Tribunal noted that, “Intellectuals' killing was a part of calculated policy. Commission of killing targeting specific class of national groups perceivably was the outcome of common plan and purpose of the perpetrators. Inherent nature and extent of killing and the class of victims belonged to suggest to conclude that the crimes were perpetrated by a collective enterprise or group i.e. Al-Bader.”

While in the case of Ali Ahsan Muhammad Mujahid the organisational structure of Al-Badr and its operational planning was addressed in detail in the case of Chief Prosecutor vs Ashrafuzzaman Khan and Chowdhury Mueen Uddin the horrific accounts of torture and killing came to the limelight. A team from International Commission of Jurists visited Bangladesh in early 1972 and published a report where the intellectuals' killing was also highlighted. The report titled “The Events of East Pakistan 1971: A Legal Study” narrated the case of the woman journalist brutally murdered. The report noted that, “The victims were taken in trucks to a deserted brickyard near Mohammadpur. The only survivor, who managed to loosen the rope with which he was tied and escaped, has described how the prisoners were tortured before being taken to be shot. The victims included women, one of whom was an editor who was found with two bayonet wounds, one through the eye and one in the stomach, and two bullet wounds.”

The brutally murdered woman was Selina Parveen and the lone survivor Delwar Hossain became a star witness for the prosecution in ICT-BD after more than 40 years. The Tribunal noted the final hours in Selina Parveen's life and observed: “Selina Parveen begged for her life, appealed to spare her as she had a kid and there was none to take care of him excepting her. But the brutal killers did not spare her. She was instantly killed by charging bayonet. What an impious butchery! What a sacrilegious butchery! What a shame for human civilization! This indescribable brutality shocks human conscience indeed.”

Excess cruelty was so shocking that the Tribunal could not contain itself to the legality of language but in their use of words reflected the humanity against whom the crimes have been committed and on behalf of whom judgment has been delivered. As the Tribunal is adjucating the cases of intellectuals' killing the judicial process has proclaimed the victory of justice over horrendous criminality. The nation after a long and lonely struggle has achieved the end of impunity for the perpetrators of genocide. Time has arrived to take a deeper and broader look on the acts of genocide, the role of ideology and the Joint Criminal Enterprise where many individuals joined the bandwagon with their complicity, abetment and incitement. Humanity had to learn its lesson to say no to genocide, to proclaim 'Never Again'. The killing of intellectuals may be an act of madness, but there is a method in such brutality which needs to be exposed and condemned to learn lessons from the past and to build a better future for all.

The writer is Trustee, Liberation War Museum.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments