The country my father wanted

We are celebrating the golden jubilee of our country's independence this year. Fifty years of existence of this sovereign state called Bangladesh; the Bengali people's thousand-year yearning for statehood finally given tangible shape and form. At the same time, however, many families across this beleaguered yet proud land are observing the absence of loved ones for that same period: a father or a mother, sisters or brothers, cousins, aunts, uncles, friends, nieces, nephews; an uncountable number lost before their time.

Because the independence of Bangladesh was not an unmixed blessing. Far too many families paid in blood and tears so that this country could be born. My family is one of those. I lost my father, Mufazzal Haider Chaudhury – a teacher of Bangla language and literature at what was then known as Dacca University; a linguist, essayist and thinker - on December 14, 1971. As many of us know, this was not an isolated incident. Hundreds of his compatriots - writers, teachers, artists, journalists, physicians, engineers – were picked up from where they happened to be, taken to a remote location, tortured and murdered; in some cases, they were shot where they stood, in full sight of members of their family. This macabre exercise started right when the Pakistani army launched a full-fledged assault on the unsuspecting and unarmed population of the erstwhile East Pakistan on March 25, 1971 – their 'Operation Searchlight' - and continued until December 16 of that year, just hours before the surrender and absolute defeat of that army.

The abductions really kicked into high gear on December 10, and on December 14, around 200 of these unharmful, gentle souls - as Bob Dylan would have put it - who were non-combatants and had not fired a weapon in their lives, were taken away from their homes in Dhaka by the Al Badr militia, collaborators of the Pakistani army. They were blindfolded; some of them taken to an abandoned physical training institute in the city's Muhammadpur area where they were beaten with iron rods, drenching their clothes with blood; some had their eyes gouged out. In the early hours of the morning of December 15, they were all taken to a place named Katasur and bayoneted and shot to death. We know all this because a gentleman named Delwar Hossain, the only survivor of the massacre of that day, has provided vivid and heart-rending account of what took place that day.

If you are a person possessed of the usual degree of moral outrage, you would have found the above account chilling, even after all these years. What had these people done to provoke the ire of those who saw themselves as their sworn enemies, to the extent that these antagonists were driven to such monstrous, indefensible acts? Most of them did not even know these people they abducted and murdered. The murderers were not soldiers performing gruesome acts in the field of war. Yet they knew precisely whom to pick up, torture and kill. And – this always gets to me – what inspired the worst savagery in them was not unkindness or hostility but certain ideas, some beliefs. On that fateful night of December 14, what the young men armed with rods and sharp weapons wanted to know of their hapless victims was who among them had written a book on Rabindranath Tagore. When my father said he had, they pounced on him with renewed ferocity.

As if writing about the great humanist poet and philosopher had made that gentle, scholarly person, a lifelong lover of beauty in all its forms, their worst adversary. A dangerous element that needed to be wiped out.

What makes this anger even more perplexing is the fact that my father was never an overtly political person, unlike many of his contemporaries who were also victims of these murderers. He never did time as a political prisoner; possibly never shouted himself hoarse in a procession. Why then did he come to this cruel end?

To answer this question, we would need to understand what kind of person Mufazzal Haider Chaudhury was, and what his aspirations were for the country he held in his heart. Since he was murdered for his ideas, we would need to understand why these ideas were so heretical from some perspectives.

He was born on July 22, 1926, in a small village in Noakhali to a father he referred to in a dedication in one of his books as a 'lover of literature', and a mother who was very literary-minded, as evidenced by the many lyrical letters she wrote throughout her life. He received a conventional religious education in his childhood and early youth, and was sufficiently enthusiastic to actually develop translation skills from the original Arabic language of his religious studies. He had inherited his parents' literary bent, however: always a good student, the high marks he achieved in the Bangla and English examinations in his school days started to draw attention. He did not have much of an opportunity to encounter Rabindranath's poetry, music and prose in his school curriculum, but what little he did find captured his imagination.

His young mind was confronted with something of a spiritual crisis at this point. Orthodox Muslim religious education had led him to think non-believers would never ascend to heaven. Yet Rabindranath Tagore, whose work was steeped in a generous, all-encompassing humanism, was not of his faith. How was he to reconcile this? His love of creativity extended to art and he used to draw the great poet's portrait, had collected many other portraits of his at different stages of the poet's life. He would look at those pictures and wonder to himself: how was it possible that this saintly man would be hell-bound? How would a just and loving God allow this?

He had a debate with his mother once on this subject, but could not reconcile it to his satisfaction. In the end, he found his own way to the answer to this dilemma, as one has to. The wider humanism he tapped into in his exploration of literature, philosophy and the arts gave him a path to extract himself from the parochialism of rote religious learning.

This is what the young man wrote to describe himself at that stage in his life: 'Life has wounded me in many ways. I lost my father early on, was raised in an environment of neglect and unhappiness. But the Creator has not been unkind in providing riches in my soul. The sadness the outside world inflicted on me was more than made up for by the bounty He had given me within.' (I have taken the liberty of translating this from the original Bangla)

That bounty helped him perform extraordinary feats. This young man from a remote village in Noakhali came 4th in the 1st division at the matriculation examination held under the (erstwhile) Calcutta University in 1942, earning a first-grade scholarship. Since the savagery of the Second World War was then going on in full force, Calcutta was at serious risk of being bombed by the Japanese, So, he, along with most of the bright young men of his time, got admitted to the Dacca Government College. From there, he passed his intermediate examination recording marks of over 75 in all of his subjects and coming 1st in the 1st division.

Owing to a series of complicated circumstances, but mainly driven by a desire to study Bangla literature, my father ended up in Santiniketan in 1944. The Shikhkha Bhaban there, under the stewardship of Sri Anil Kumar Chanda, was then a private college. It is there that the young man started studying for his Bangla Honours degree following the curriculum of Calcutta University.

This was a life-changing experience for him. The wide-open environment of Santiniketan, along with the easy friendliness of his teachers and fellow students, the relaxed rules, the focus on learning not to pass exams but to improve oneself and develop true insight into the subject matter, the emphasis on the joy to be derived from music, dance and the creative arts, the pristine beauty of the nature that surrounded him – all of these worked on his young, sensitive, beauty-seeking soul like a magic spell. His spirit took flight in this environment. He would never be the same again.

As a non-collegiate student, he came 1st in the 1st class in the BA (Honours) examination of Calcutta University in 1946 with record marks in Bangla. This was an inconceivable thing for a Muslim boy from the backwaters of East Bengal to accomplish back then, and this singular achievement also brought unprecedented glory to Santiniketan. Overjoyed, the revered, hermetic professor of the Rabindranath chair in Santiniketan, Probodh Chandra Sen, gave him the nickname 'Mukhojjol' - loosely translated, one who makes us proud. It was not just Muslim students from East Bengal he brought glory to that day, but the whole of Santiniketan.

Rathindranath Tagore, son of the great poet, gave a leather-bound copy of the Gitanjali as a gift to my father when he heard what the young man had achieved. "My father would have been the proudest of you if he were still alive," he told him. The famous Surendra-Nalini gold medal was also awarded to my father to recognise his record marks. And incidentally, that record was still intact in 1958, at the time of the centenary of Calcutta University, when he was awarded the Sir Ashutosh Gold Medal to commemorate the highest marks ever recorded by anyone in a Bangla Honours examination in the University's hundred-year history. The Vice Chancellor specifically mentioned the young scholar's accomplishment in his speech that day.

In 1946, my father got admitted to the Master's programme at Calcutta University to continue his studies on Bangla language and literature. By then, horrific communal riots had started to break out in Calcutta. This, combined with the financial difficulties he was having at that point, led my father to heed the urging of his teachers at Santiniketan and return there to study for his MA degree.

He sat for the internal examination of the Lok-Shikhkha Sangsad of the Bishwa-Bharati University in 1948, again coming first-class-first and being awarded the Shahitya-Tirtha title. This was considered the equivalent of an MA degree at that point, but it was not officially approved by Calcutta University. Given this, Professor Probodh Chandra Sen advised him to complete the formality of getting an MA degree from Calcutta University. But in his own mind, the young scholar was already past that stage. He obtained a scholarship from Bishwa-Bharati and started on a research project on the works of Rabindranath Tagore under the guidance of Professor Sen.

By then, of course, the partition of the sub-continent was already a reality, and traveling to Santiniketan, which was now part of West Bengal in India, from his home in East Bengal which now fell in Pakistan was becoming increasingly difficult. So, the young man, still in his early twenties, decided to return home. But his homeland was not as welcoming as he might have imagined. His Santiniketan degree was not accepted as the equivalent of an MA by Dacca University, so he was deemed ineligible for employment there.

It is at this point that we begin to see the glint of steel underneath the mildness of this young man. He refused to sit for an MA degree from Dacca University and accepted a position as a script writer at East Pakistan Radio. Here again, his ethical principles – some may have termed it obduracy – got in his way. After having worked there for about a year, he was told by seniors that his preferred attire of panjabi-pajama was not suitable for the workplace. He resigned from his job right then and there.

By then, his reputation as a scholar had already spread – he was a regular speaker at literary events and contributor of essays to newspapers and periodicals, and tales of his academic feats at Santiniketan had also filtered through. He had stints of teaching at Jagannath College and St Gregory's College – later renamed Notre Dame College – and serving as one of the managers of the Dacca Centre of the Lok-Shikhkha Sangsad during this period.

In 1953, he reached a momentous decision. Since Dacca University would not back down in its position regarding his Santiniketan degree, he finally opted to sit for an MA examination under DU. He appeared for both the 1st and 2nd parts of the exam together and came first-class-first in part 2.

This is not a decision that sat well with him. He saw it as a defeat, a capitulation to faceless officialdom. He was an acknowledged scholar and teacher for more than seven years by the time he joined Dacca University as a teacher in 1955.

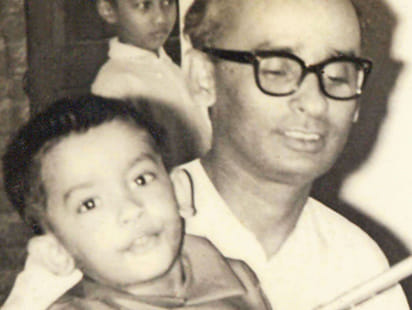

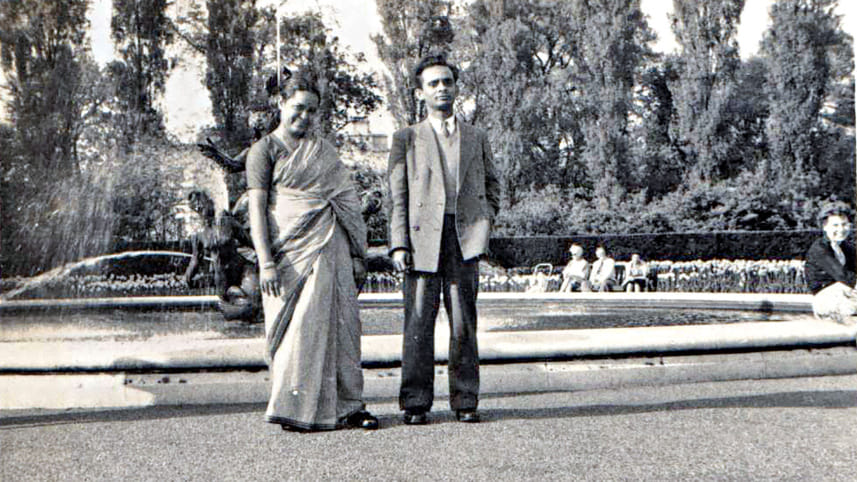

He got married to my mother, Tahmina Monowara Nurunnahar, in 1956. They had to wait 8 years for their first child, my brother Suman, to be born.

In 1958, my father was awarded a British Council scholarship to study linguistics at the London University's School of Oriental and African Studies. After traveling with my mother to London and spending two years of his life on his research, he fell out with his supervisor over differing views on the project and started for home with the work left incomplete. This had an adverse impact on his standing back home - he was thought to be too sensitive, verging on being self-righteous, by some of his peers.

Here again, however, we see his unwillingness to back down in the face of powerful adversity when he knew himself to be right. He paid a high price for this trait many times over in his life, and it is this same characteristic that possibly led this affable man to stare down powerful adversity and brought his life to its tragic end.

He never relented on championing the unique cultural heritage of the Bengali people, be they Muslim, Hindu or of any other religious persuasion. The fact that the oeuvre of Rabindranath Tagore was essential to make sense of the cultural context of the modern Bengali people, that recognition of Kazi Nazrul Islam's syncretic beliefs and avowed secularism was as important in understanding him as is his 'rebel' persona, that the inclusion of Michael Madhusudan Dutt, Bankim Chandra Chattopadhyay , Nabin Chandra Sen, Hem Chandra Bandopadhyay -- all of the great poets and writers who enriched Bangla language and literature in the pre-partition era -- he never tired of communicating these self-evident truths in his writings and lectures. In the profoundly paranoid and xenophobic climate of the East Pakistan of the '50s and '60s, these were subversive, even dangerous statements. But my father never backed away from making them.

The dismal truth is, in 2021, the year we are celebrating the golden anniversary of our independence, these ideas have once again become 'controversial', after decades of stoking the flame of religious intolerance by those in power.

It is this steadfastness in spreading his ideas that earned my father a place in the list of East Pakistani educationists, physicians, journalists, writers – all the prominent individuals who espoused secular/progressive ideals - that Ghulam Azam, then the head of the Jamat-e-Islami party of East Pakistan, drew up for Major General Rao Forman Ali in September 1971. Following this list, many of these individuals were rounded up, tortured, and murdered – most of them just two days before the independence of Bangladesh.

I am the final surviving member of my father's family. My mother passed away, at 58 years of age, in September 1990, and my brother died of a sudden heart attack in December 2011, when he was just 47.

I have thought long and hard about why the lives of my mother and my brother turned out the way they did; why they left us so early. I remember the many indignities my mother suffered in her untiring efforts to ensure a good life for us. How she continually had to struggle against adversity after losing her husband. She had lost her mooring to this world, but soldiered on regardless, valiant and alone.

I have stated before that my brother was born to my parents relatively late in their marriage. I have only recently begun to understand how traumatised Suman would have been at losing his father when he was just seven-and-a-half years old; this treasured child who was pampered for all he was worth in the first years of his life, only to be left facing a bleak and uncertain future. I am convinced both of them would have had much longer, more fulfilled lives had they not had to deal with the horror of my father's abduction and murder.

As for me, I was just four when he was murdered. I realised very early on that the world was a hostile place for us, that I should not expect too much out of life. So, I learned to adjust.

And as we know, ours is by no means a unique story in Bangladesh. Innumerable families across this blood-soaked land suffered the same fate in 1971, and beyond.

I have gone into some length in describing here what kind of person my father was, and the homeland he held in his heart; the ideas he ultimately died for. The country we see around us, where religious intolerance has run rampant, where money and power decide whether one has recourse to equity and justice, where secularism is ridiculed and looked upon with contempt, where the rich get ever richer and the poor are left to fend for themselves, where misogyny, graft, deception and nepotism are the order of the day, where the institutions that uphold democratic values have been rendered impotent, does not embody those ideas.

Make no mistake, the country has made great strides in many ways in these fifty years. Our GDP has increased manifold, we outstrip our South Asian neighbours in terms of many human development indicators, the participation of women in economic activities has grown commendably, we have very effectively exported blue-collar workers to various parts of the globe, our ready-made garments industry is a runaway success story acknowledged the world over. But the fundamental principles we fought the liberation war for are not reflected in the Bangladesh of today.

If we value the sacrifices of the martyrs of 1971, if we want all those lives lost to have some lasting meaning, we have to defend those ideas. They are worth fighting for.

Tanvir Haider Chaudhury is a son of Martyred Intellectual Mufazzal Haider Chaudhury. He currently runs a branded food company and occasionally contributes essays to periodicals

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments