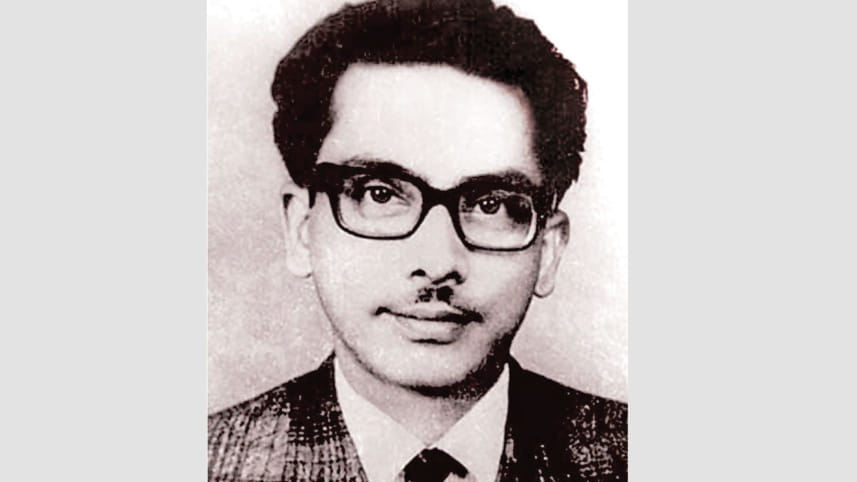

Bhai Zahir Raihan ...

My brother Zahir,

I do not have the audacity to console you, the same way I couldn't console the mother of Sheikhpara's Akram. Do you know when I kept being reminded of you? The day the Pakistani army surrendered in Dhaka.

I was in Jashore at the time.

I came out when I heard the sound of aeroplanes. I could see a white plane flying over my head, towards Dhaka. When we were in Monirampur, I saw it returning. For some reason, it made me think that I was watching one of your documentary films from the future.

This dream of mine felt even closer to reality when I heard on the radio that very evening that you had started for Dhaka with your unit. Then I heard you missed your flight at Dum Dum because of traffic problems on the road, so you arrived a day later.

On the other hand, I was still dreaming of going to Dhaka from Jashore. I wondered how surprised you would be to see me in Dhaka all of a sudden. The Pakistani army still hadn't given up arms in Khulna. They had absolutely demolished the city. They went house to house, fishing out Bengalis from their houses and killing them like rats from holes. When defeat became inevitable, groups of armed traitors fled, some towards the villages, some towards the rivers, looking for a way to escape. The Pakistani army still held bases in Faridpur and Rajbari. The army and the Rajakar forces were still shooting at the roads from their bunkers in Bhatiapara. Thus the road from Jashore to Dhaka was still closed. A way might have opened up in two or three days, but within 24 hours there were many people anxious to get to Dhaka. Some of them had their wives and children stuck behind enemy lines, some of them had parents. No one knew how their families had been all these months, or even if they were alive. Having witnessed this wave of worried individuals with my own eyes, I decided not to go to Dhaka for now. Because my going might mean someone else not being able to.

Besides, to be honest, I feel more of a connection to Chattogram than to Dhaka! Because my first experience of Dhaka wasn't pleasant. Let me tell you why.

The first time I stepped foot onto Dhaka was at least 28 years ago. Comrade Jyoti Basu and I went there together. The party commune was possibly at G Ghosh Lane at the time. Some moments after we got there, a group of people marched out with sticks and logs, ready for battle. Before leaving, they told us, "Sit and wait. We will come back soon." They returned right after dark, seemingly victorious. Later I learned that some boys from a leftist party had stabbed one of our people. This is how they took revenge for that, with sticks, on a culvert somewhere.

That was the first time I had spoken with Satyen Sen and Ranesh Das Gupta. But the person whom I'd met for the first time even before this in Kolkata – I don't know if you still remember him, Zahir – was Somen Chanda. And let me say this even if it doesn't sound right, among all our contemporary communists, Somen Chanda had all the elements and the qualities needed to become a big writer, he was the only one.

But it was long before my first visit to Dhaka that, while leading an anti-fascist procession of yarn mill workers, Somen Chanda was killed by a group of anti-communist leftists. It was in the memory of Somen Chanda that on that day, we formed our Anti-Fascist Writers' and Artists' Association.

That's why right after reaching Dhaka, this violence between leftists left me a bit disheartened.

What happened the day after could not have made any newcomer like Dhaka at all.

There was a meeting of the district committee in the party office the next morning. Around midday, news arrived that a riot had started between Hindus and Muslims. A combined group of Hindu and Muslim comrades escorted me to Narayanganj that very day. And when I got to Narayanganj, there was no way to tell that there was a riot going on in the city right next to it.

Therefore, the length of my first visit to Dhaka was less than even 24 hours. That too with trouble at every step. But within that short span of time, I met people that I could love, people who were ready to sacrifice it all for their fellow man. I met some of them after two decades in Kolkata. They still hadn't changed colours, only the colour of their hair had turned white. Finally out of jail, or coming out of hiding, these people will enjoy the open air and sun for the first time in 25 years in independent Bangladesh.

Even though I'm a son of Kolkata, I cannot help admitting – there was only one instance in my life when I was jealous of Dhaka. When Jukto Front decimated Muslim League and won the election the first time standing on the groundwork laid down by the Language Movement. The literary conference was organised right after that. A big group from Kolkata went there as brotherly representatives. The city of Dhaka looked so beautiful at that time that I couldn't describe it with words. It wasn't just the new houses and the bright lights. The Language Movement birthed new life into the stones of Dhaka.

I will never forget that city full of life. The walls still had Jukto Front written on them, and pictures of boats drawn. Rickshawpullers pulled their rickshaw in a manner similar to that of rowing a boat. Those days will always remain etched in my memory, unharmed.

You must have been just a boy back then. That was when I met your dada, Shahidullah Kaiser.

When I was in Jashore, Mehbub told me, "Shubhashda, stay two more days. I will take you to Dhaka." I left Jashore the next evening without telling Mehbub. I restrained myself from going to Dhaka looking at the faces of all those anxious travellers.

I'm glad I didn't go that day.

I saw the horrible news on the paper upon returning. Shahidullah Kaiser's name was on the list. I still held some hope in my heart, because the suspicions based on capture, there was a slim chance they weren't completely true.

I went to Lake Garden in the morning to find Opu and Topu alone at home. Shuchanda had gone to Hari's place to call you.

When I saw Shuchanda, her face was swollen from crying all day. Shahriar let me know that someone from Dhaka came and told them that what they feared was true.

We can't bring back someone who has left us. But what we all were worried about was you. Because if they had you in their grasp, everyone in Bangladesh knew what they'd do to you. A band of defeated, mad dogs were hiding out in the alleys of Dhaka, and even now they wouldn't let you go if they found you. More than the pain of losing dada, we were all fearful of what might happen to you. The only thought we had was to find a way to warn you. Shahriar, Hari, and Santosh spent the entire day in front of the telephone that day.

Zahir, why am I writing you this letter? Not to console you for the grief of losing dada. Even though I know, Shahidullah was much more than just dada to you. Shuchanda told me in between tears, "Dada built him up with his own hands. All he has become today is because dada was behind him."

When I didn't know you, I read your book – Hajar Bochor Dhore. When I spoke on the radio about literature, I quoted from your book and said that I'd never read a better Bangla book written about the life of a destitute farmer. I was asked by so many about the book on buses and trams, it was beyond count. I told them they couldn't find the book here, it was from East Pakistan.

I found out much later that you were a film director. I found out even later that you were Shahidullah Kaiser's brother.

A letter shouldn't be drawn out much longer than this. Before I finish, I just want to let you know that I've gone and watched Jibon Theke Neya in the meantime.

There's nothing stopping me from saying this now, but I was afraid. I was afraid it wouldn't be exactly how I wanted it to be. Because at the end of the day, it was still a movie shot during the rule of the military. But all my fears ebbed away inside the hall. The entire audience became at one with your movie. They were laughing, they were crying, at certain times, they were seething with anger. During intermission, after the show, they were only talking about the movie. I couldn't tell when I found myself immersed into a group of those ordinary people. With the enormous pressure of working under the military government on your chest, not only did you find a way to breathe in secret, you managed to spark a flame to the pile of dry gunpowder. Not only have you honoured the brave, you have also honoured the art as well as the artist. You have told the story of a home, but that home spanned the entire nation. I have heard that the movie has many flaws. I am tired of watching flawless movies. Let there be flaws, right now we want some fire in our lives.

My brother Zahir, Hari came from Dhaka and told me that you started taking photos as soon as you landed in the airport. Then after spending the entire day taking photos of different places in the city, you couldn't even look at your house once you got there. They had smashed it all up, destroyed everything.

When you ran and ran and finally reached dada's house, you were at a loss.

That was when you learned the most devastating news you've ever heard in your life – Shahihdullah Kaiser was no more.

No, Zahir, I will not console you.

There are still many dead bodies rotting in the fields and the creeks, waiting to be buried. Many are still dead and missing.

Let's raise our flags half mast for one day, in memory of all the Bengalis in Bangladesh and Indians killed, let's darken our cities, and observe a day of no cooking in all our homes.

You came into your home taking pictures and then you were stunned by the pain of loss, now shake it all off and come back out.

Subhash Mukhopadhyay was one of the foremost Indian Bengali poets of the 20th century. The article was originally published in his book titled Khoma Nei (1972). It is translated by Azmin Azran.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments