Looking back into the mirror

In the apocalyptic days of early December of 1971, when Dhaka was a beleaguered city, there were very few shops that would remain open at dark. A brave man of indeterminate age ran one such shop in Dhaka stadium that sold cigarettes, paan, soda, tea and biscuits. This shop drew people who ventured out even in those life threatening days if only for some open air, and some gossip. The shop owner was a store house of information. He knew about every attack that was launched in the city by the Mukti Bahini, where the Pakistani troops were, and what were the places to avoid. I was a frequent visitor to the shop in my fugitive days in Dhaka in November and December. What was most inspiring during these visits was the upbeat spirit of the shopkeeper. Despite the doom and gloom that was almost everywhere in the city, the shopkeeper kept a smiling face and comforted us by saying that the end of Pakistan was near. It was very soothing to hear his almost prophetic utterance even though the circumstances around us pointed to a different direction.

A few days after liberation when I went to the stadium to greet my shopkeeper friend, I found him morose and downbeat. He was not his cheerful self because he did not like what he saw. In a sorrowful voice he said that he did not know how to separate the freedom fighters he had rooted for from the thugs who had aided and abetted the Pakistani army. These brigands had melded with the freedom fighters, and in the name of cleansing the city of Pakistani occupiers, had begun an endless operation of plunder.

I never saw the shopkeeper again as he closed his shop and moved on. But his comment stayed with me, and I would be reminded of it when events in our country ushered in an era of national politics comprising of people who were not exactly fighting our war. I would be reminded of it when attempts were made by some of our own people to denigrate our Liberation War and its history, change the core values of our freedom struggle, and try to alter our national identity based on ethnicity and culture.

In the last forty-four years, we have gone through many changes. With demographic changes, the older population who had witnessed and suffered in the war of liberation have aged or passed on leaving the younger population the legacy of the history of the war and their interpretation of it. Under normal circumstances, the demographic changes would have had no adverse effect on the history of liberation had the new generation been given a truthful and consistent account of our liberation struggle and its heroes. Unfortunately this was not to be so because the political changes that followed a few years after our liberation distorted the true history of our struggle for liberation and the core values that it stood for. The changes happened because the political leadership changed not through a democratic process, but through violence, which would haunt the nation for a long time at frequent intervals. These changes were sometimes forced, and sometimes inevitable, but they also brought in their trail many casualties in addition to human deaths.

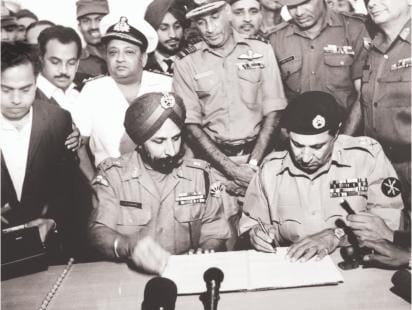

The first casualty of the political change was democracy itself. Some may argue that it began when a one party system was introduced in 1975, but its real demise occurred with the military coup of August 1975, and authoritarian governments would replace democracy for a decade and a half thereon. However, this political change did not only replace democracy with authoritarianism, it also rehabilitated people who had stood against our liberation and had collaborated with Pakistan in suppressing their own kind.

The second casualty was dumping of the principles of our Constitution and state policy. The principal victims were the ideals of Bangalee nationalism which became Bangladeshi nationalism, and secularism which gave way to upholding Islam as the state religion. These changes were to have a serious impact on our subsequent politics and shaping of political ideology and political groups in the country. A constitutional change allowing the formation of political parties with religious affiliations not only allowed the return of Jamaat-e-Islami and its infamous leader to Bangladeshi politics but also led to the growth of a plethora of religious parties in the country.

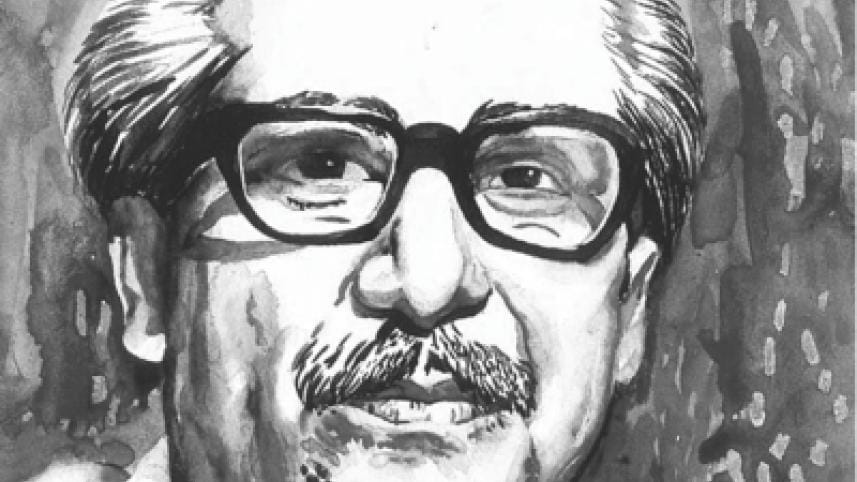

The third and perhaps one of the most pernicious consequences of the political change was the distorted information of the Bangalee struggle for independence and its major hero Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman purveyed to the young generation by the governments of the period and its immediate successor. The change enabled the opponents of the Liberation War to question the contributions of our founding fathers to our liberation and replace the history with an alternative version that would mislead coming generations.

The collective effect of these changes on the nation would be, however, visible only after three decades. During this time a whole generation would be raised with a misleading view of our liberation struggle. These changes would also help the growth of religion based politics and lead to rise of intolerance and bigotry in politics. The political rehabilitation of the enemies of liberation and their newfound position of strength in national politics would give a different interpretation of Bangladesh's identity to the world which is much removed from the language and culture based identity that we all thought our liberation from Pakistan gave us. A new spectre of religion based identity would pose a challenge to us.

Unfortunately, many of these changes went unnoticed for a long time. These changes surfaced only during the political turmoil of the last decade when the country appeared to be polarised on some fundamental national issues such as war crimes trial, and restoration of secularism in the Constitution. Political division of the country into two camps on such basic issues brought into the fore just how far the country's political landscape had changed in four decades.

Today, when we look back into the mirror, we see remarkable progress in the national economy, but we also see our growing distance from the four original pillars that our nationhood was based on. Our political growth has been stunted not simply because we deviated from these goals, but also because our leaders never seriously tried to instill in the nation the values of democracy, nationalism, and secularism. While some of the changes that have happened may be irreversible, it is possible to guide our next generation in the right path if we have the will. Values of democracy, nationalism, or secularism cannot be instilled in a country by simply inserting them in the Constitution or by rhetoric; they have to be instilled in people's minds by way of example and education. As we enter our 45th year, we hope that we have the right kind of leadership to guide the nation to these ideals by practice and not by rhetoric.

The writer is a political analyst and a commentator.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments