As a War Heroine, I Speak

In 1972, while working closely with various National and International Organisations to rehabilitate the raped and tortured women of the Liberation War, Nilima Ibrahim (1921-2002) interviewed some of these heroic women and kept a detailed journal of her experience, which she later published in a book form in 1994. Needless to say, Ibrahim used fictitious names for her characters in order to protect their privacy.

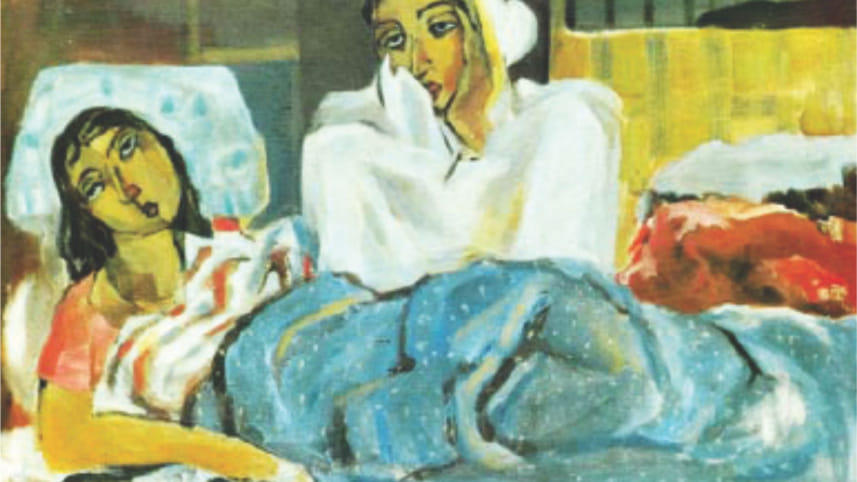

In her reportage, Neela Haider, the main narrator of Ami Birangana Bolchi (As a War heroine, I Speak), discloses the harrowing struggles of these women of war. This excerpt from Chapter One is the story of Tara Nielsen, a courageous woman, whom the narrator first met at the Dhanmondi Women's Rehabilitation Centre in 1972, and then later in Denmark.

A longer version of this translation is available online.

lived in Rajshahi during those raging days of 1971. My father, a medical doctor, set up his private practice in a provincial town there. Once a government official, my father left his job after the language movement of 1952 and moved to Rajshahi where he built a small house with a nice garden. My grandmother passed away before we moved to that beautiful house. By the end of 1970, my oldest sister got married and moved to her new home in Kolkata. My oldest brother, a medical student in his final year, joined the political movement that was getting stronger every day. My mother was a little annoyed but my father welcomed my brother's decision whole-heartedly. My mother would worry about most things anyway; she would often grumble whenever my father stayed late at his office. Father used to laugh and tease her, saying “Haven't you heard what Sheikh Mujib said? 'Grab whatever you have and confront your assailants…'” Mother used to frown at him and retort, “Yes, I have heard that many a times, but what weapons do you have to attack your assailant with?” My father always said, “I have you and I have a son and a daughter here with me; and I have my two strong hands.” Even though he always tried to assure her, I knew he was somehow disturbed. I knew he hardly slept those days; he would wake up in the middle of the night and pace restlessly on the verandah. I did not know the cause of his anxiety. It could be that he foresaw the signs of an impending danger.

The situation started to grow worse by mid March, but people stayed unified and did not lose courage amidst all threats. The darkest night of March 25 descended upon the country to cast the dice of destruction upon us. Things started to change rapidly after that night. On the morning of the 26th, we saw strangers walking around our house. Mother did not stop counting her prayer beads and Father kept pacing restlessly on the verandah. We hid ourselves inside the darkness of our own house like a bunch of rodents. By the morning of March 27, my parents and I were ready to flee. We hastily packed and left the house stealthily before dawn, planning to reach a distant village where no one could harm us. There was no rickshaw on the street, and there was no transportation available anywhere. We kept walking as fast as we could. We walked for hours until our local Chairman's jeep suddenly pulled over and blocked our way. “Where are you going, Doctor?” The Chairman of our precinct asked, “Come, let me give you a ride to your destination.” My father politely refused the offer and we resumed our walk. Suddenly a group of four or five thugs jumped out and pulled me into the jeep. No one fired any gun, and no one got killed. I didn't know what happened to my parents. The jeep ran at high speed to reach its destination. I had no sense of time and place and I think I passed out for a moment. When I opened my eyes, I found myself sitting on a chair, surrounded by strange faces. A man in military uniform sat inquisitively in front of me. I realised I was in a police station. Since the Army Officer behaved like a gentleman, I decided to ask him, “Why have I been brought here?” He replied, “It's for your own safety.” I looked around and saw a few girls sitting, scattered and sobbing. Some of them were wailing and were being chastised for doing so. Sister Neela, I can remember everything so vividly, as if it just happened right now! They brought bread and bananas and tea for us. I kept pleading to the Army Officer asking him to let me go. In response, the Army Officer told me he was quite impressed to hear me speak to him in flawless English. The whole day passed slowly as I sat there. The Chairman of our precinct came back in the afternoon, and I fell to his feet the moment I saw him. “Uncle, please help me!” I pleaded, “Uncle, you used to say you treat my father as your own brother, don't you remember? Don't you remember uncle that I am your daughter's friend? Your daughter Sultana and I go to the same school; we study in the same class, remember? We always play together. I used to visit your house. You have known me since I was a little child. Uncle, please, please help me! Save me! Show some pity!” The Chairman shook me away from his feet and left; and thus I knew I was left there as a piece of meat, to be devoured by the hungry tiger. And that moment, as the Chairman turned around and left, I watched a human being transform into an animal. I only saw animals after that day, animals, all around and over me; I did not see a human being until December 16.

The officer caressed me as he took me with him. He drove the jeep and kept telling me stories of his glorious manhood. But I was not paying attention to him. My head was busy planning an escape. I was sitting in the front passenger's seat and two security guards sat at the back. As the Officer kept weaving his stories of heroism, I suddenly jumped from the running jeep. When I woke up, I found myself lying in a hospital bed. My head was wrapped in bandages and my whole body was really sore. The small hospital was mostly run by male staff; there was no other girl there besides me. They brought a little girl from somewhere to look after me. The girl was homesick and kept crying the whole time. It took me about three days to recover, and all the while, the Officer always came in the morning and stayed with me the whole day. You know, there is this belief in our culture that before you slaughter an animal, you have to make sure that the sacrificial animal is healthy and disease free; those men were trying to make sure I was fit for the slaughter. After the third day, I was able to sit up and move around a little; the Officer left in the evening, promising to be back for me the next day.

The first man who violated me that night was a Bangalee, my own countryman. I was too weak to fight back, and too shocked to absorb the truth. My head was not strong yet, and my body lay powerless, being violated by a bestial Bangalee man. But that was only the start. I don't exactly remember how many of them raped me that night, maybe six or seven, or maybe more. When the Army Officer came next morning and found my disheveled body, he created havoc and ordered his men to discipline those men at the hospital. He then took me with him to another place. As he helped me get inside that house, I held his hand and started pleading for freedom, “You have saved me from those animals,” I said, “You have saved my life and I am grateful for that. Please let me be free now, please let me go, brother, yes, I will call you my brother because you are of my brother's age. Please, brother, let me go to my family!” Suddenly his eyes flashed and his body language changed. He grabbed me and pulled me by my hair, “Brother, right! Tell me where your brother is hiding! Tell me! Where is he?” I said, “How would I know? I am here with you and have no way to communicate with him.” He spat on my face and called me names in his language. I fell on the ground and remained there like a mound of clay. Why did he suddenly get so angry? Was he mad at those men at the hospital? Or, was he angry because he could not rape me first? Of course! He had missed his chance to be the first one to violate my body. But that was not my fault, was it? It was his fault that he was not there that night. It was his failure, not mine. I mean, who was I? I was nothing but an object. I had no heart, no mind, no soul. I just had a body; a body that they could fondle and molest and torture; a body that they feasted on; a body that needed food when hungry, and water when it was thirsty. A body that sometimes needed to rest so that it could serve later. I was their object of pleasure. They pushed me around and dragged me along; they shared my body as their prized food and devoured me whenever they pleased. I clenched my teeth and whispered “Joy Bangla” while my body endured their cruelty. They kicked me and spat on me, and they bit me like hungry animals if they heard me chanting for the victory of my country.

There is a saying in our village: cat, turtle and woman are the three creatures that don't die easily. You can torture them as much as you want, but still they breathe and survive. It was possible for us to endure their brutal sexual torture only because we were women. Men wouldn't have the mental strength to survive such physical assault. They needed our bodies for their recreation, so they had to feed us well and keep us somewhat clean, and they had to make sure we were usable. There were ten or twelve women with me in that camp, between the ages of thirteen to thirty-five, and most of them were collected from the neighboring villages. There was one girl—very pretty and smart—who was a final year student at the Rajshahi University. Two of her brothers were in the Pakistani Army, who later defected to become freedom fighters. She always tried to comfort me saying, “Have faith and stay alive; I know we will see victory.” She told me it was the month of July. Oh, dear God! I did not know it was that long since I had descended to hell. They took that University educated girl away one evening; I guess they needed to please some big Officer with a better war trophy.

We were not allowed to wear sari or a dopatta because they considered them a health hazard. Some girl in some other camp had hanged herself using her sari, we were told. So we only wore a blouse and a petticoat: torn and dirty, barely covering us. Once in a blue moon, they would bring a supply of cheap clothes and threw them at us, the way rich people distribute clothes among the beggars on the eve of a religious festival. Every year during the time of Durga festival, Father used to ask me, “What kind of sari do you want this time, my baby?” I would say, “I will take anything you get for me.” My father would hug me and pray for me, saying, “The house you will run one day will be one of peace and blessing.” Oh, my dear father! I wish you knew your daughter was not meant to become a respectable wife of one man! She was an ill-starred girl, born to please many and more: she was destined to be a concubine, a wife of hundreds of men, a wandering courtesan.

I hadn't seen my own face for months, since that ominous day of March. How do I look now, I wondered. They gave us no mirrors because a piece of a broken glass could be used as a weapon. We might cut and kill ourselves. There were no glass windows in the room where we were kept. They made sure we stayed safe and alive. ALIVE! Did they have any idea what we wanted? We were not enduring all the pains so that we could die there like animals! I wanted to live and see the day when I would take revenge. Yes, I thought of taking revenge! Oh, what would I do to them who had brought me to this level! How would I punish those! How would I punish that man—that Chairman of my precinct—whom I had respected as an uncle! What would I do to him?

I sometimes thought about Shyamal. Where is Shyamal now? Shyamal had finished his final Engineering Exam and was in Dhaka, waiting for the result when the war broke out. Is he alive? Is he dead? He must be dead by now; after all, he is a man. He was a good-looking man though, quite handsome, and I always dreamt of building a future with him. But he was shy and was not good at expressing his feelings. His sister Kajoli was my classmate, and she was the one who once spoke on his behalf, “Tara, do you know my brother is in love with you? He loves you very much indeed!” I felt so embarrassed that day! But God knows where he is now; maybe he is dead, or maybe he has joined the freedom fighters, or maybe he has gone to India to be with his other family members. His older sister and uncles lived in India. He would be safe there, I told myself.

Mati Mia, our rations supplier became our only link to the outer world, our mole. He would throw us information in the pretense of cursing. Sometimes he would scream praises for his bosses. He told us it was September and the Pakistani soldiers were getting ready to go home to their families; after all, they were almost ready to declare a victory. From Mati Mia's coded message, we understood the war was about to end in our favour. We could sense the advent of a change in the camp as well; we could hear gunfire all day long and watched the signs of worries and uncertainty in the faces of our captors. Outside, they played radio in a loud volume and cursed nonstop in their language at the voice of the newscaster. It was not a broadcast station from Dhaka or Rajshahi that they listened to; the Bangla pronunciation of the newscaster sounded like it was Akashbani, the radio station from Kolkata. A male newscaster delivered news in quite a dramatic voice, and the moment the news was done, we could hear the voices of Rajakaars, bantering the Hindus for broadcasting false reports. We stayed quiet and tried our best to gather information of the outside world from Mati Mia and from the intermittent radio broadcast that we could occasionally hear.

One of the girls of our camp died from excessive bleeding. The fifteen-year-old girl was at an advanced stage of her pregnancy. Her name was Mayna. She bled profusely and convulsed like a slaughtered goat for hours. We banged on the door and screamed for help, but no one responded. By evening, her face turned pale blue and she grew too weak to move and slowly exhaled her last breath. The oldest woman in our camp—known to us as Sufia's mother—brought a blanket to cover Mayna's cold body. We sat by her the whole day. Finally they came in the evening and took her away. But no one returned that night to satiate their carnal hunger; it seemed they were somewhat shaken by the death of that girl. Or maybe their sexual desire was gone and they were getting ready to kill us all. We spent every moment in terror, anticipating the blow of death to fall on us any moment.

It was wintertime and our blankets were not thick enough to keep us warm. We sat close and tried to keep each other warm, covering our bodies with thin blankets. Days were quiet and nights went mute. No one entered our rooms anymore; no one came to give us food or feed on us. “Have the son of the bitches fled?” Sufiya's mother screamed one day. The moment she said that, we all stood up and ran to the door. We started banging on the door, screaming, crying, and asking for help. I don't remember how long we screamed and shook the door, but I remember hearing voices, synchronized into a series of loud and distinct slogans, “Joy Bangla! Joy Bangabondhu!” I hugged Sufiya's mother as if she was my own mother and started crying. As a group of men broke the door and entered our room, we started running in fear, looking for a place to hide. Sufiya's mother approached the group and asked them their identity. The men said they were freedom fighters, but we still did not believe them. We heard more people chanting “Joy Bangla” outside the premise and heard the sound of a car engine. We started screaming frantically, “Joy Bangla! Joy Bangla! Joy Bangla!” Another group of nine or ten people now entered our room, Medical College Hospital. I found myself surrounded by female patients, a lot of them. It was lunchtime when I arrived there, and a nurse put a plateful of rice and curry in front of me. I burst into tears as I took the plate from the nurse's hand. She stroked my hair and talked to me affectionately, asking me to eat. I was starving and ate voraciously. A simple meal of rice and curry, but it was the best food I had eaten! I felt alive. What a fool I was to think that I was alive! I wish I knew that day how many times I had to die before I could finally be alive again!

I was pregnant, the doctor told me. She asked me if I had any place to go. Should she contact anyone on my behalf? “I have no one,” I said. “I have nowhere to go and no one to call. Do whatever you do with helpless women like me.” And that's when the kind doctor sent me to the Dhanmondi Women's Rehabilitation Centre, where you saw me. When I was staying at the female ward of the Medical College Hospital, I used to see a large crowd of visitors—men and women—glancing at us with inquisitive eyes. The attending nurse told me they came to see the heroines of the war. “Heroines of the war? Who are they?” I asked the nurse. “You and the other women like you,” the nurse continued: “The Prime Minister has declared that women who have given their honour and lost their dignity for the country are no less heroes and contributed equally for the freedom of the country. He honoured these brave women of the war by calling them his war-heroines.” I lowered my head in respect to my leader, the architect of our freedom. He had given me the highest respect by awarding me the title of a war heroine. I felt proud, but then again, why did I still feel depressed? Why couldn't I control my tears?

I was getting desperate to contact my family. I wrote down my father's name and address in a piece of paper and gave it to Mosfeka Mahmud, the Executive Officer at the Rehabilitation Centre, requesting her to contact him on my behalf. I spent countless hours, waiting eagerly for my father; but he did not show up. The house was all broken into pieces and he was busy fixing the house, he wrote. But he would come soon, very soon, he wrote again. “O, dear Father!” I screamed inside my head, “You are just like the rest of them; you are no exception!” I started avoiding all people after that—all the outsiders. The Polish Medical doctor who was in charge of the Rehabilitation Centre was very nice. I requested her to train me as her nurse and she gladly agreed. I put my worries and my frustrations behind and concentrated on work.

I finally agreed to go through the abortion process. It was a difficult decision, but I was well aware of my situation and I knew I had nowhere to go. No one would accept my baby in this world. So I decided not to mother an unwanted baby. Tell me, how can a mother in her right mind agree to part with her child? Sister Neela, do you remember Marjina, the fifteen-year-old girl? The poor girl was desperate to keep her son with her and did not want to put him for adoption. Every time you visited the centre, she would scream at you, thinking that you were there to steal her child. You eventually took the baby and sent him somewhere to live with a new family. But you stopped visiting the centre after that. Why, Sister Neela? Were you heartbroken after you took away Marjina's son?”

“Yes, I was.” To tell you the truth, of all the rehabilitative works that I have done, sending Marjina's son to Sweden with his adopted parents was the hardest one. I even pleaded with Bangabondhu, asking him to allow Marjina to keep her son with her. But the Prime Minister did not agree. He said, “Please, sister, put all these fatherless children for adoption and give them a chance to live a healthy life somewhere else. Besides, what will I do with these children of rapes? I do not want to nurture them in this country.” I had no other options open, Tara.”

“And I decided to fight my own battle, alone. Father suddenly showed up one day. He had grown old in one single year. He put his arms around me and held me tightly as he cried aloud, like a little child. I cried the same way the other day, when a group of us went to meet Bangabondhu, our beloved leader and Prime Minister of the country. I cried like a little girl when he spoke to us tenderly, calling us his brave mothers: "You all are my brave mothers and have sacrificed your most precious wealth to gain freedom for your country! You are the bravest of all heroes of any war. You are my courageous war heroines! You sacrificed everything for the country, and now I am here for you. I promise to take care of you, my brave mothers.” The words of Bangabondhu brought tears in my eyes, but my eyes shed no tears when I stood close to my own father and watched him cry like a helpless child. Why couldn't I cry, do you know, Sister Neela? What made my heart so cold? What was I thinking about? I freed myself from my father's embrace and asked him, “Should we start for home today? Then I have to notify the office….” And he faltered. “Not today, my girl, “He said in a hesitant voice, “The house is not completely fixed yet, and I have a houseful of visitors. Your maternal uncles are visiting us; your sister Kali and her husband are planning to visit soon. I will come back for you when they are all gone.” I distanced myself from him and said in a cold voice, “Father, I understand; but please don't come to see me anymore.” I saw pain and shock in his eyes. “No!” He said, “Don't say that!” He handed me a small fruit basket and left. My father visited me a few more times after that, but he never asked me to go home with him.

By the way, Shyamal, the man of my dream also came to visit me. He came for a totally different purpose though: he wanted to see a war heroine with his own eyes. My brother also came from Kolkata and brought me a nice sari. My brother grew up to be quite a strong and brave man, you know. He had the courage to speak about things that my father was hesitant to utter. “Don't you take any whimsical decision to come back home, Tara.” My brother told me, “We will come and visit you here, but you should not think of returning home. And one more thing, you also should not write letters to us. You are doing fine here, anyway. I have got a good job and the government has given us a good chunk of money as compensation. We are mending the house, and…” I stood up and left the room in the middle of the conversation. I walked away and did not look back at him, not even once. And the next time he saw me, I was not his helpless wretched sister Tara anymore; I was a proud and accomplished Mrs. T Nielsen.”

Translated by Fayeza Hasanat.

Born on January 11, 1921, Nilima Ibrahim was a Bangladeshi educationist and social worker. In her most noted work, Ami Birangona Bolchi, she highlighted the courage and perseverance of war heroines of the Liberation War. Her other literary works include Bish Shataker Meye (1958), Ek Path Dui Baank (1958), Sharat-Pratibha (1960), Begum Rokeya (1974), etc.

She earned her Bachelor's in Arts and Teaching from the Scottish Church College, following it with an MA in Bangla literature from the University of Calcutta in 1943. She also earned a doctorate in Bangla literature from the University of Dhaka in 1959.

She was a professor of Dhaka University's Bangla department. She also served as the chairperson of the Bangla Academy, and as the Vice Chairperson of the World Women's Federation's South Asian Zone. She was honoured with the Bangla Academy Award (1969), Ananya Literary Award (1996) and the Ekushey Padak (2000), apart from Independence Day Award (2011), which was awarded to her posthumously. The prolific writer passed away on June 18, 2002 at the age of 81.

Fayeza Hasanat is a PhD student in English, University of Central Florida.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments