Those days of 71

Here we present an excerpt from Jahanara Imam's seminal autobiography, Ekatturer Dinguli. This diary entry was made three days after the military picked up her husband, Sharif, youngest son, Jami, and eldest son, Rumi, a freedom fighter, from their residence at Dhanmondi. Although Sharif and Jami returned to tell the horrific tales of their detention, her eldest son, Rumi, did not.

Sharif, Jami and Masum tell an unbelievable, inhumane story of barbarity and cruelty. Sharif doesn't speak much usually; he gave a summary of their two-day, two-night imprisonment in his characteristic manner. I had to extract the detailed descriptions from Jami and Masum.

That night, the soldiers made Rumi and Jami walk to the main road from the house. The road was lined with quite a lot of jeeps and lorries. The military police, that had surrounded our house, now came out of our lane and that of Mr. Kashem, and gathered on the main road. Captain Kaiyyum then made the five of them stand in a line on the side of the road. A jeep from the Kampala Hotel Building on the opposite end moved forward and stopped in front of them, its headlights on them. Captain Kaiyyum mumbled something or the other to someone sitting inside the jeep. Then coming back towards Sharif, he grasped Rumi's arm and said, 'You come with me.' He made Rumi sit in the jeep, and asked Jami, Masum and Hafiz to follow them in Sharif's car. Some military men also squeezed into the car. The jeep with Rumi and Captain Qaiyyum went first, followed by Sharif's car, and finally the rest of the lorries and jeeps. Eventually they stopped in front of the MP Hostel. There, the five were made to stand in a line once again. Once again, the headlights were focused on their faces. An army officer, standing in a corner of the balcony, enquired, “Who is Rumi?” After identifying Rumi, he asked them to stand on the balcony to one side. In those few seconds, pressed against each other, Rumi whispered, “None of you admit to anything. You don't know anything. I haven't told you anything.”

After a little while, some sepoys took Rumi inside. Some other sepoys took Sharif and the rest to a medium-sized room. There was a sofa set there, but they were made to sit on the floor.

Then began the infernal. Every few minutes, Pak soldiers would come and interrogate Sharif, Jami, Masum and Hafiz. “Where have you kept the arms?” “Where did you do your training?” “How many soldiers have you killed?” Answers to these were naturally in the negative, and with that would commence the beating. And such beating it was! Blows to the chest, kicks in the stomach, sudden smacks with the rod from the back – eyes would strain to come out of their sockets – pokes on the back and chest with rifle butts; smacks on the face, head, back — every inch of the body with canes, sticks, and belts; make them lie facedown on the floor, and then stomp on them with boots, squashing their elbows, wrists and knee joints. It was the same thing in the other rooms; the cries and moans of imprisoned Bangalees, the mirth and mockery of the Pak soldiers would reach their ears. It was as if the prisoners were their toys, and they were having a grand celebration having found so many playthings. One group would come and after abusing them physically and verbally, leave. A few minutes of respite, till another group would resume this pernicious play.

The Pak soldiers were very careful about one thing – they would make sure to not beat a prisoner so much that he would die. They would beat him just enough so that the prisoner would feel unbearable pain, so that blood could gush out of their noses and mouths, their fingers broke; but they didn't die. If someone fainted, they would splash water on his face, give him a break — revive him just enough so that he would be ready for more pain.

In the meantime, one by one, they would be called to another room — a Colonel was sitting there — Colonel Hejaji. One by one, he would ask them innumerable questions. After taking Sharif into the room, he made him first sit on a chair, asked what he did, how many children he had, how many people were at home, how old Rumi was, what he studied — these kind of things. Sharif answered all these questions, and added that Hafiz had just come from Chittagong, and that he had no inkling of what was going on in Dhaka. Besides, his uncle was the DC of Dhaka.

Then Colonel Hejaji asked when Rumi had left for the Liberation War, where he had received training. Sharif answered that he had no knowledge of any of this. The conversation thus far had been quite civil, but now Hejaji said vehemently, “You don't know what kind of vile boys your son mingles with, does vile things with?” Sharif said, “My son is now grown up, he studies in the university, who he hangs out with, what he does – is it possible for me to keep track of him?” Mockingly, Hejaji asserted, “Then it appears you are an unfit father. You have not been able to fulfil your responsibility of guiding your son on the honest path.” Sharif, now furious, exclaimed, “Can you say with certainty who your son is hanging out with, where he is going?”

After bringing Sharif back to the room, they took Hafiz. The stub of the plane ticket from Chittagong was still in Hafiz's pocket; by showing it, he could prove that he really had come to Dhaka that very day. Then, one by one, they took Jami and Masum. As one went in, the rest would continue to be beaten. When he returned, he, too, would be beaten. This continued till the morning.

Then the sepoys took them to another room, where a great surprise was awaiting them. It was a small room, about six foot by eight foot. A horde of people sat along the walls, on the floor. Sharif and the lot were astonished to find Bodi and Chullu among them. They didn't know anyone else, but they soon made acquaintances with everyone. Just as the Pak soldiers left the room and locked the door from outside, everyone started whispering and introducing themselves. Altaf Mahmud, his four brothers-in-law Nuhel, Khonu, Deenu and Leenu Billah, artist Alvi, Sharif's engineer friend's two brother-in-laws, Rosul and Nasser, Azad, Jewel, Dhaka TV musician Hafiz, Morning News reporter Bashar, owner of Neon Sign Samad and many more. Altaf Mahmud's shirt was drenched in blood near his chest; there was still blood smeared on his face; his eyes and lips were swollen. Both bones between Bashar's left wrist and elbow were broken; only a handkerchief was somehow wound around the broken bones, hanging feebly. And in that condition, his hands were tied at the back. There was blood on Hafiz's nose and face; the beating was so brutal that an eye had melted out of its socket and was now hanging over his cheeks. The military had wrung and broken Jewel's fingers, which were already injured a month ago, as if they were jute.

A while later, there was the sound of the door opening, and everyone fell silent. Talking was prohibited. If the Pak soldiers heard anyone speaking, they would beat them. They brought in Rumi and some other boys. Someone said in Urdu, “Sepoyji, I'm very thirsty. Please give me some water.” In reply, the Sepoy swivelled his belt and rope and hit indiscriminately, then closed the door again. An outraged voice exclaimed, “Executioners! Executioners! They won't even give us water? More beating if you ask for water?”

After a few minutes, as someone sitting by the wall shifted his position, another cried, “Oh! You can see a tap there!” Everyone was shocked: there was a tap on the wall; its presence had been shrouded by the swarm of bodies pressed against each other. Everyone drank some water from the tap. A boy took some water in the cup of his hands and helped Bashar drink.

Whispered conversations resumed. Information was exchanged about when and how everyone had been caught. Bodi was caught on August 29 around 12 noon. That day, he had attended a meeting with Rumi and others in the house on Road no. 28. Afterwards, Rumi went to Chullu's house to listen to music. Bodi went to his close friend Farid's house for a chat. The military picked him up from that house. Samad was picked up around 4 in the afternoon. The military went to Azad's house at midnight. They also apprehended Jewel, Bashar, Azad, his cousin's husband and two other guests. [Only Kazi had escaped.] Apparently he had suddenly jumped on the Captain in an attempt to snatch the Sten from his hands. It was so sudden and unexpected that the military, taken aback, began to shoot at random. In the commotion, Kazi escaped.

Alam's house was quite close to Azad's big house in Maghbazar, in Dilu Road. The army went there around two in the morning. From there they picked up Alam's uncle Abdur Razzak and his son Mizanur Rahman. Around 1.30 am, Kazi had arrived at their house, almost naked. He said, “The Army just conducted a raid on Azad's house. In the scuffle, I managed to escape somehow. Give me a lungi, and a Sten. The Army will inevitably come to this house. I will stop them.” Alam's mother gave him a lungi and said, “Son, you must leave at once. We will take care of ourselves.” As soon as Kazi left, Alam's mother and four sisters helped his father climb over the low boundary wall to the other side. Just then, the army surrounded the house. There was a small hidden concrete chamber beneath the floor of Alam's kitchen where arms were stored. Upon arrival, the first thing the army asked was: where is the kitchen? Everyone knew then and there that the army had already found out about the arms and ammunition dump. The Pak soldiers went to the kitchen, removed the firewood and dug out the arms and ammunition, smashing the concrete slabs with crowbars. Since the only men in the house were Alam's uncle and his cousin, the army picked up both of them. The poor souls had come to Dhaka from Khulna only a few days ago. Even though they didn't know or do a thing, they were being beaten to death. They could not begin to comprehend why they were being beaten at random.

The military had arrived at Shahadat's house in Hathkhola at three in the morning. Since they couldn't find any freedom fighters there, they seized one of Shahadat's brothers-in-law, Belayat Chowdhury. The poor man worked at P.I.L. He had come home from Karachi on leave and never gone back. He was at the village, but as fate would have it, he had come to Dhaka only 10-12 days ago. The poor man was not involved in anything at all, but thanks to his freedom fighter in-laws, he was now being subjected to torture.

At Chullu's house, the military arrived around 12/12.30 am. Chullu's brother M. Sadek was a high up government official. Chullu was apprehended from his government residence, No. 1 Tenament House, Elephant Road.

The army went to Altaf Mahmud's residence around five in the morning. Their house was in Outer Circular Road, opposite the Rajarbagh Police Line. They had rented the house next to Sharif's friend, Mannan's residence. That house belonged to Mannan's elder brother, Baki. A few days ago, Samad of Neon Sign had brought a huge trunk filled with ammunitions and explosives to be stored at Altaf Mahmud's. It was buried in the courtyard behind Mannan's house. Once they arrived, the first thing the army did was whack Altaf Mahmud on the chest with such tremendous force that blood instantly gushed out of his nose and mouth. Then they made him and Samad dig out the trunk from the courtyard. The army had brought Samad with them to the house. They made Altaf's brother-in-law place the trunk in the car. Alvi was in their house at the time. The Pak soldiers were searching for him bellowing in Urdu, “Where is Alvi?” But fate was on Alvi's side; Altaf Mahmud had managed to tell Alvi in those few seconds, “Your name is Abul Barak. You're my nephew; you've come from the village.” Thus, as he pretended to be Abul Barak, his life was spared. Nevertheless, he was picked up by the Pak soldiers along with the rest.

Mannan's two brothers-in-law and their mother used to rent the second floor of their house. Since the two houses were adjoining, and the trunk had been salvaged from Mannan's courtyard, the Pak soldiers also apprehended Rasul and Nasser. Lucky for Mannan, he was in Chittagong at the time and was thus spared. An income tax officer who lived on the second floor of Altaf's house, his son and nephew were also picked up.

After Rumi was brought to the small room, he told Sharif, “Baba, even before they caught me, they already knew about our action in Road 18 and 5 on the 25th, who was in the car, who had shot when, how many we killed, they knew everything. So it is irrelevant whether or not we admit anything. But the four of you must not admit to anything. You don't know anything at all, that's what you will repeat to them. They might question you one at a time but all of you must say the same thing. You never had a clue of my whereabouts. Make sure there is no incongruity.”

Altaf Mahmud said the same thing to his four brothers-in-law, Alvi, Rasul and Naser, “You, too, will say the same thing, that you don't know anything. I am the only one who has done anything. I'll confess what I have to.”

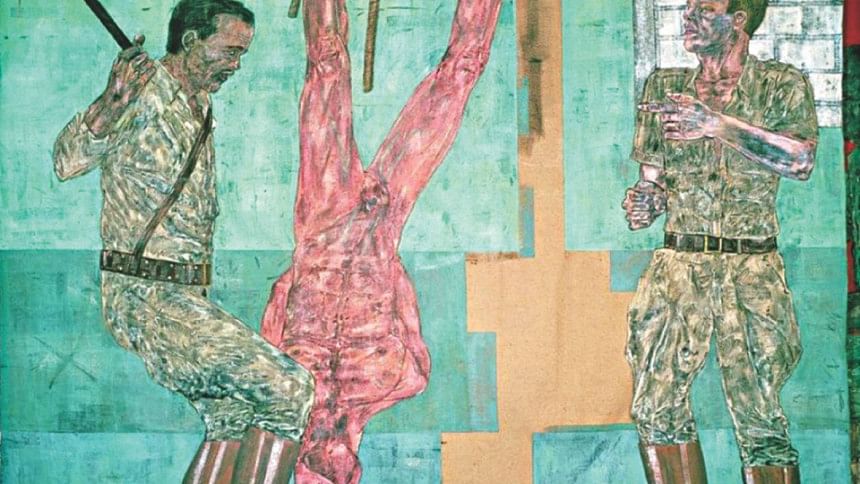

Time passed. At intervals, the Pak soldiers would enter the room, randomly beat up people, curse them, and then leave. Then they [the prisoners] would whisper amongst each other. After some time passed, Pak soldiers took away Rumi, Bodi and Chullu. A little later, they removed Altaf Ahmed and all others with him. Then they took Sharif and the lot. Meanwhile, no one knew that, at 9 in the morning, Hafiz had been released. No one had any sense of time or place. Who was being taken where, when – no one can say with certainty anymore. The only thing that occupied their minds was the continuous torture they were subjected to. They had seen how Shapan's father was hung from a fan and beaten senseless with a thick stick, with a stiff coiled rope, how they had revived his consciousness by spraying water on his face only to resume their torture. The Pak solders were especially angry at him as his son, Shapan, had escaped right through their fingers. His other son Dalim was already fighting in the war.

The army, who had gone to Ulfat's house in search of the guerrilla, had picked up his father Azizus Samad when they did not find him there. I know him by name. His wife Sadeka Samad is a headmistress of Anondomoyi Girls' School. I have known Sadeka apa for a long time. Ultaf has played a role in some of the daring actions in Dhaka. They couldn't find the son, so they got the father and tortured him inhumanely.

That evening, I had spoken to Shubedar Gul and Jami on the phone. Jami now revealed, “After getting your call, Gul took some money from us and bought us all kabab and rotis.”

Around 11 at night, they took everyone, meaning all those caught between the midnight of 29th and 30th morning – except Rumi – to Ramna Station on jeeps. After entering their names, they placed everyone in a room. When they arrived at the station, it was very quiet. After they entered the room, they saw prisoners passed out on the floor, sleeping. But once the Pak soldiers locked them up and left, an incredible scene took place. The ones who had seemed to be fast asleep now sat up all at once, and made a fuss over them, asking about their health and condition and taking care of them. Who had broken what, who was bleeding, where was the pain – they were putting bandages on some, massaging some, giving Novalin to others. Those who smoked were given cigarettes. Then some rice and curry arrived -- two mouthfuls of rice and a little vegetable curry. Even paan was arranged for those who wanted to chew on the beetle leaf. These prisoners too were patriotic Bangalees who had been captured by the military. They too had lived through the MP Hostel experience. They told the newcomers, “They will take you to MP Hostel again in the morning tomorrow. They'll torture you some more. Let us teach you a trick. Pretend to faint after one or two lashes, close your eyes, and hold your breath. Then they would pour water over you and let you be. This way you'll get thrashed a little less.”

The next day, they heard the sound of an approaching car at 7 am. Again, a big bus. All the windows of the bus were shut once everyone boarded. Again, MP Hostel. After a while, they were taken to another house at the back. Apparently everyone had to give statements now. In that house, another infernal episode commenced.

Giving a statement meant an army officer would hear the statements of the prisoners one by one, interrogate him, hear his answers and note them down in a piece of paper. The torture conducted upon the prisoners during the 'statements' exceeded by far the torture they had been subjected to in the previous two or three days. The officer asked the prisoner a question, and if the answer was in the negative, began to kick him, beat him with a stick, smack him with a rifle. If one answered in the negative continuously, then the officer lost his patience and took a break. During that break, the soldiers would hang the prisoner from the ceiling and beat him ceaselessly with a coiled rope. Some would be made to lie on their back with their hands and feet tied together such that their bodies took the shape of a boat. They would suffocate, but couldn't scream. If a prisoner was particularly stubborn, they would switch on the fan at high speed with his feet tied to the fan. His hanging head would spin and spin with the fan till there was blood in his nose-mouth-eyes and he lost all consciousness.

It was way past noon while statements were being extracted through this hellish process. Around 1.30, Sharif and the other three were brought to the Colonel's room in MP Hostel. The Colonel said, you can go home now. Sharif asked about Rumi. Colonel replied, “Rumi will be released tomorrow. We haven't finished taking his statement.”

Translated by Sushmita S Preetha.

Jahanara Imam, a writer and political activist, was born on May 3, 1929. She is widely remembered for her efforts to bring those accused of committing war crimes in the Bangladesh Liberation War to trial. She was also known as Shaheed Janani or Mother of the Martyr.

In her professional career, she worked as the of Head Mistress of Siddheswari Girls' School. She was also the first editor of the monthly women's magazine called Khawateen. In 1971, her elder son Shafi Imam Rumi joined the Mukti Bahini. He was picked up by the Pakistani army on August 29, never to be seen again. During the war, she wrote a diary on her feelings about the struggle, which later became one of the most important publications about the War of Liberation. In 1986 this diary was published under the title Ekatturer Dinguli. Her other literary works include Anya Jiban (1985), Jiban Mrityu (1988), etc.

Jahanara Imam received several awards for her contribution in Bangla Literature. She won Bangla Academy Award in 1991. She also received Independence Award and Rokeya Award posthumously.

Sushmita S Preetha is a journalist and researcher.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments