Revisiting 1971 sagas through the lens of a silent witness

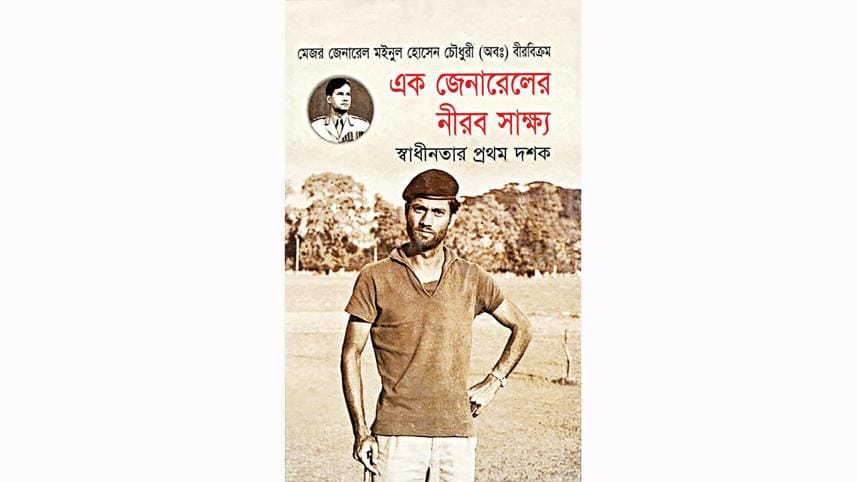

Major General Moinul Hossain Choudhury (Retired), Bir Bikram (1943-2010), was one of the twelve majors of the then-East Bengal Regiment who joined the war after a revolt at the first instance of resistance, which was when the Pakistan Army unleashed a spectre of violence against the people of this land. A tiny section of relatively junior officers made up the initial backbone of the regular Bangladesh Army during the resistance movement in 1971. He never wrote a comprehensive book or memoir on the war of liberation, but events from 1971 frequently came up in his writings, particularly in his two books. When looking back at the last 50 years, his testimony is invaluable for deciphering some of the events that took place in 1971.He was candid when he elaborated why he joined the war when he was serving in the Pakistan Army and revolted against the commanding military, which had been decisive. He pinpointed that for the sake of honour, self-respect, and Bengali nationalism, he came to a position for the supreme sacrifice and, thus, he joined the full-fledged war in 1971. When he looked back on the events of 1971 after a considerable period of time, he was frustrated by observing the post-liberation developments. Revolutions often disappoint their participants by their eventual outcomes as facts do not necessarily bear out dreams and expectations. The extent of Moinul Hossain Choudhury's frustration might have become all the greater after, as an independent country, Bangladesh made a name for itself for corruption, lawlessness, and lack of direction. He suggested that the cause of these regressive developments was a lack of 'total faith and commitment' among various professionals who could have played a significant role in 1971. For instance, he estimated that there were around 200 Bengali Army officers at the time of the war, and less than half of them joined the fight.

The picture in the civil administration and the police administration is yet more dismal, since–according to Moinul Hossain Choudhury–their contribution was not up to par either. In his recently published memoir, Akbar Ali Khan, mentioned that only 14 Bengali CSP officers, out of more than 100, joined the Liberation War.

Lack of proper planning and guidance from the political leadership at a critical juncture certainly exacerbated the situation. A lot has been discussed about the planning and preparation of the liberation war. Political leadership that had spent their entire political careers in a constitutionalist system might not have been well predisposed for facing a full-scale war. Unlike the transfer of power in 1947, the independence of Bangladesh had not been possible only by political demand and negotiation.

Moinul Hossain mentioned some incidents that illustrate the importance of critical analysis of macroscopic and microscopic aspects of 1971. He joined the war from the Jaidevpur Cantonment. He dutifully participated in many frontal wars and battles with colossal courage to face great danger, and he served in both the 1st and 2nd East Bengal Regiments. He was present in Dhaka with his 800 soldiers on the 16th of December when the Pakistan Army had surrendered to the India-Bangladesh joint force. Before reaching Dhaka, he was advised by Indian Brigadier Misra to stay at Narsingdi, but instead, he headed towards Dhaka. The history of the Second World War came to his mind when Russian generals and generals of the other Western allies were contesting with each other regarding who would take control of Berlin first.

Contesting decisions on the basis of actual field situations is not uncommon in war history. In the 1971 war, General Jacob's denial of the decision made by Indian Chief of the Army staff General Manekshaw has been regarded as a textbook example of this fact. Manekshaw was undermined by Jacob in the capture of Chittagong and Khulna. Instead, the General Jacob marched to Dhaka by avoiding the towns in between and using secondary routes to reach the capital city, which ultimately ensured the quick fall of Pakistan in this land. When we retrospectively look at the particular decision of Moinul Hossain Choudhury regarding reaching Dhaka on the 14th of December, we can see that a fraternal but often contesting relationship was prevailing between Bangladeshi and Indian army officers.

As his troops were marching to Dhaka, he observed that the people of Dhaka were leaving. Foreseeing a heavy street fight waiting before the final victory in Dhaka, he felt tense about the massive casualties. Since the moral courage of Pakistani armies was very low as an invader who committed numerous crimes and lost their Air Force in the first stance of December, they did not opt for a street fight. When the fall of Dhaka took place, Moinul was cautiously vigilant with his troops to maintain law and order in the newly independent country–a most challenging effort.

A few civilian freedom fighters informed Moinul that some of the affluent families in Dhaka were inviting the Indian soldiers to family parties. These guys had made the same offering to the Pakistan Army in the occupied period. Referring to the book of Siddiq Salik, an important Pakistani army officer in Dhaka, Moinul pointed out that such events took place in the occupied Dhaka. In the celebrated film Guerrilla, there was also a scene that takes place at a meeting between Pakistani army officers and Bengali civilians. Money invariably speaks in the times of conflicts and human tragedies. 1971 was no exception. Thus, his silent witness would contribute a lot to the perceptions regarding what happened in the liberation war in 1971 and afterwards.

Priyam Pritim Paul is pursuing his PhD at South Asian University, New Delhi.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments