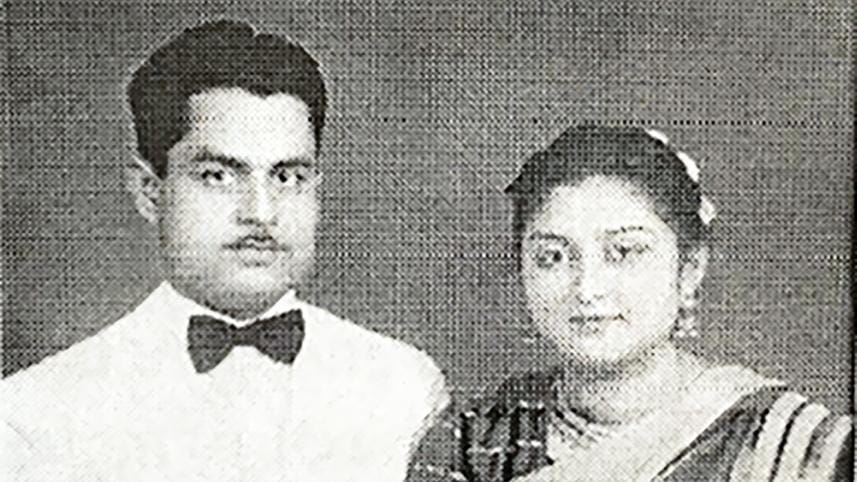

Remembering Shaheed Lt Col Syed Abdul Hai

It was the tumultuous times of 1971. At the end of March, I was recovering from some major injuries sustained from a devastating car accident – in which my father Ghyasuddin Ahmed Chaudhary was killed and my brother Faruq Chaudhary and I got hurt. At that time, my sister Naseem and her husband Lt Colonel Syed Abdul Hai, with their three children Ashfaq, Adel and Aref, had come to stay with the family for a few days.

Both Lt Colonel Hai and Naseem were politically very conscious and used to participate intensely in political discussions regarding the rights of the Bengalis and the discriminations they suffered due to the arbitrary actions of Pakistan's autocratic military rulers.

Colonel Hai was posted on deputation in the Ghana army from 1965 to 1969. Upon his return to Pakistan in 1969, he was appointed the commanding officer of 7-Field Ambulance in Jashore Cantonment. After the devastating cyclone of November 12, 1970, Colonel Hai, as CO of 7-Field Ambulance, was extensively involved in the relief works and reconstruction activities in the cyclone-hit area of then East Pakistan's southwestern region, where his unit was temporarily posted.

Col Osmany had become a frequent guest at our house after the death of my father, who was like an elder brother to him. Our place at Dhanmondi actively became a centre of political discussions, frequently visited by many pro-Bengali leaders of eminence. Colonel Hai capitalised on the opportunity to meet and talk to leaders like Abdus Samad Azad, Barrister Amirul Islam and others.

Subsequently, it was revealed that Colonel Osmani's meetings with Lt. Colonel Hai had been monitored by the army's Inter-Services Intelligence (ISI).

Colonel Hai, with Naseem and their three sons, returned to Jashore on March 13. On their way home by road, their car proudly displayed the 'Shadhin Bangla' flag with the country's golden map at the centre, along with a black flag indicating their solidarity towards the ongoing non-cooperation movement.

While entering the Cantonment, the car was stopped at the army checkpoint through which no car – without an authorised tag on insignia – could get in. The incident was reported to army intelligence and the station commander, Brigadier A Durrani.

The next few days leading up to March 25 was tense, to say the least. Any pro-Pakistan slogan was retorted by Bengali soldiers shouting 'Joy Bangla' on top of their lungs, particularly at the field ambulance unit. The 1st Bengal Regiment was undergoing an exercise at Chaugacha in Jashore. Brigadier Durrani used to call Colonel Hai and ask him to control his troops, to which Colonel Hai's usual response was that they were just expressing their views.

The tension finally reached its peak when the news of the army crackdown and atrocities committed in Dhaka came to the fore.

The 1st East Bengal Regiment was ordered back to the cantonment from the 'exercise' and the decision to disarm the Bengali elements – when known – acted as a unifying force to create a sense of togetherness among the Bengalis, fortifying their resolve for resistance.

Unfortunately, Lt Colonel Jalil, the commander of the 1st East Bengal, who happened to be the senior-most Bengali commanding officer, declined to step up to the occasion. His unit returned to the cantonment on March 29. Early in the morning of March 30, Brigadier Durrani removed Col Jalil from his commanding position.

On March 30, Colonel Hai received an urgent telephone call and rushed to his office. Usually, his wife drove him to his office but on that morning, he left on his own. "Be prepared for any eventuality," he told Naseem right before leaving.

The shelling of Bengali units by the Pakistan Army started from early in the morning. Bengali soldiers of 1st East Bengal, under the leadership of Captain Hafizuddin Ahmed Bir Bikram, broke open the armoury and started defending themselves from the attack of 25-Baloch, who had started firing with machine guns and three-inch mortar fire. The Bengali personnel of the 7-Field Ambulance, commanded by Lt Colonel Hai, joined them in their brave resistance.

Brigadier Durrani, along with an army contingent, came over to Colonel Hai's house, and in the presence of his wife Naseem telephoned Lt Colonel Hai to surrender with a white flag.

"Anything may happen any time now. The children will be there for you. Khuda Hafiz," these were the words of Lt Colonel Hai, during his last call to his wife.

At mid-day, when the sounds of the shelling and shooting had receded, a group of soldiers from 22-Frontier Force and 27-Baloch Regiment, led by Captain Mumtaz, approached Colonel Hai's office from the rear door. They banged the door open, identified Colonel Hai and opened brush-fire. "We don't want to see Lt Colonel Hai alive anymore," were the orders from the higher-ups.

After that, the Pakistani soldiers left without any more shooting.

For two days, we didn't know of anything that happened in Jashore Cantonment.

I was Deputy Commissioner of Khulna (greater) and my friend and colleague, Khondokar Asaduzzaman was Rajshahi's DC. Both of us were withdrawn from the field and posted as joint secretaries of the commerce and industries and the finance department respectively.

Syed Shahid Hussain, a Pakistani national and former CSP – who was Additional Deputy Commissioner of Khulna – knew that I was related to Colonel Hai. In his book titled "What was once East Pakistan" (2010), Shahid recounted the events of March 30, "That evening an army captain was recounting the day's exploits. I was saddened to learn from him that they or perhaps he himself had killed our good Bengali doctor, an army Colonel. I expressed my horror at the unwarranted murder of an innocent and well-meaning human being. This remark provoked the young captain to point his gun at me because he felt I was defending a traitor: for the Pakistani troops every Bengali was a traitor."

At nightfall on March 31, an eerie silence prevailed in a curfew-afflicted Dhaka.

Around 10:00pm, a convoy of machine-gun-mounted jeeps and an ambulance arrived at our Dhanmondi house. At first, some of the soldiers with rifles surrounded the house. We partly removed the curtains and saw through the windowpane that they opened the main gate, through which an ambulance entered. A coffin was brought out by some armed personnel.

There were sounds of heavy boots on the balcony and loud knocks at the door. Amma asked us to stay behind and opened the door. To her great shock, she saw Naseem standing there with the children. "Where is Hai?" Amma asked her. Naseem stretched out her hand and slightly pointed to the coffin laid on the balcony.

"There should be no protests and any mourning should be strictly kept indoors. The burial should be done within the grounds of the house," these were the instructions of an officer who brought Hai's body.

Our brave Urdu-speaking driver brought a Moulvi Sahib from the neighbourhood mosque, who recited the holy Quran for the peace of the departed soul. The next morning, the army officer on duty, after much pleading and a reference to the HQ, relented. Domestic aides from our house and one or two other neighbours were sent to prepare the grave close to my father's at the Azimpur graveyard, where he was buried only about two months ago.

Escorted by an army contingent and troops mounted with machine guns, we took the dead body to Azimpur in an ambulance. During the entire ritual, we were kept under the strict surveillance of ever-vigilant armed troops. There were no loud mournings. Just absolute, stunned silence. With muted utterances from the Quran, the body was laid inside the grave, after we saw the last glimpse of Shaheed Syed Abdul Hai.

And that was the moment when we realised – the war of independence had already started.

Enam Ahmed Chaudhury is a former Chairman of the Privatisation Commission.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments