Bangabandhu arrives in Delhi …

January 1, 1972. An emergency meeting of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, chaired by the Foreign Minister, was held that evening at my Dhanmondi residence. The Foreign Minister told me to prepare for his India tour within four to five days. The main objective of the tour would be to build world opinion in favour of Bangabandhu’s immediate release from Pakistani prison.

On January 5, 1972 we arrived in Delhi. Next day, we met Prime Minister Indira Gandhi. She expressed India’s interest in providing all kind of support needed. She said that she was hopeful about Bangabandhu’s freedom, and wished us a successful tour.

On January 7, meetings were held between Foreign Minister Abdus Samad Azad and several Indian ministers. In regards to the question of Bangladesh’s recognition, the Indian diplomats shared their opinion on the international situation. Almost all of them were of the idea that the release of Bangabandhu would accelerate the process of Bangladesh’s recognition.

On January 8, 1972, while we were having a meeting with Indian officers at the Indian Foreign Ministry, all of a sudden, the doors to the meeting room opened with a loud thud, and JN Dixit came in with a look of excitement on his face.

News just broke out that Sheikh Mujib had been released; he had already left Pakistan.

The meeting adjourned and the room filled with spontaneous applause. An ordinary day turned into something extraordinary to remember. The excitement-filled moments are etched in my memory.

It had been decided that the Bangladesh delegation would return to Dhaka as soon as possible. Only the Foreign Minister, Abdus Samad Azad, and I, the head of protocol of the Bangladesh Ministry of Foreign Affairs, would stay back. We were to accompany Bangabandhu on a special flight from Delhi to Dhaka. Another decision was made: on the dawn of January 10, after reaching Palam Airport, Bangladesh’s newly freed president would deliver a speech in English in front of the reporters and people who would be present to welcome him. The task of drafting this speech fell upon me.

What do I write in a speech for someone whom my eyes had never met? What do I write about his journey of victory, whose return to the country is like a sunrise over the shore of a bloody sea?

My pen slowly overcame the inertia amidst the loneliness of my room at Ashok Hotel. Bangabandhu’s journey of victory is similar to a journey from darkness to light, from captivity to freedom, from desolation to hope. He is returning to the country after nine months. Within that time, “my people have traversed centuries”. He is returning to “turn victory into a road of peace, progress and prosperity”. His return to the country has the solace that truth has at last triumphed over falsehood, sanity over insanity, courage over cowardice, justice over injustice and ultimately, good over evil.

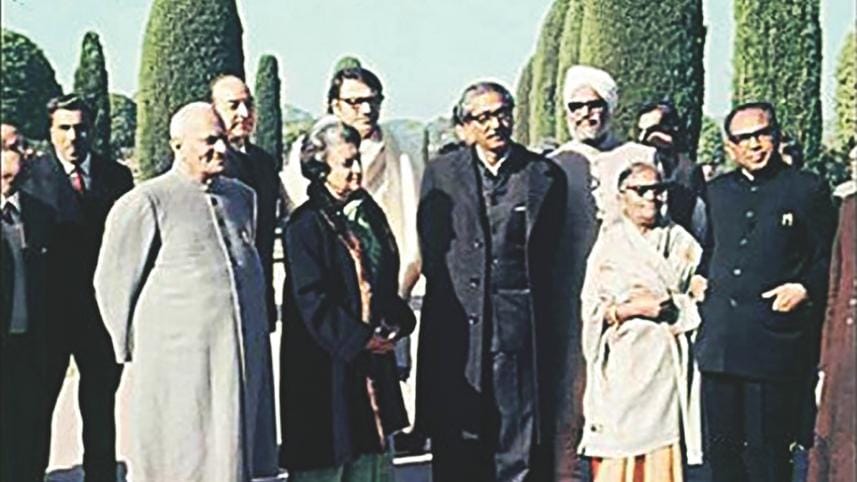

That incredible morning of January 10, 1972. Palam Airport, 8:10 am. The silver Comet aircraft of the British Prime Minister arrived slowly. Then came a state of ‘shrilling silence’. The staircase was added. The doors opened. Standing with a smiling face was the new country’s president – tall and handsome; suddenly facing a speechless crowd. With extreme passion and a booming voice, he uttered two words: Joy Bangla. Claps, hugs, excitement, and hazy memories amidst tears. President Giri, Indira Gandhi, members of the Indian cabinet, diplomats and hundreds of journalists. Cameras, microphones and televisions; rallies in the nearby Cantonment area. A heartfelt reception by the crowd on both sides of the road. Presidential building. The blurry memories of the Palam Airport keep coming back. Even amidst a prominent crowd, memories of only the head of the state of this new country, dressed in a deep gray-collared suit and a black overcoat, afloat. His thick black hair was a bit dishevelled due to the countless greetings and hugs in the midst of the cold winter air. A 21-gun salute echoed across Delhi in honour of our president. Bangabandhu attended the parade. Then, “Amar shonar Bangla” and “Jonogon mon” were played by brass band. Bangabandhu thanked India and the Indians in his ceremonial speech at the airport. “You all have worked so untiringly and sacrificed so gallantly in making this journey possible.” He remembered the people of his country. “When I was taken away from my people, they wept, when I was held in captivity, they fought, and now when I go back to them, they are victorious.” I saw his teary eyes from a distance. Those tears were of love, pride and happiness.

After the events at the airport, the rally in the winter morning was also a different experience. A motor rally went to the meeting place from the airport. Prime Minister Indira Gandhi was with Bangabandhu. She gave a brief speech in Hindi initially. Bangabandhu had a written speech in English in his pocket. However, that speech remained in his pocket. He started his speech in Bangla. “Mrs Indira Gandhi, ladies and gentlemen…” Applause began before his speech ended and then there was some more applause with every line he uttered. While sitting amidst the crowd, I felt as if a song were playing, made of his speech and the applause all around. After the speech, a motor rally carried us to presidential building in New Delhi.

My main responsibility that morning was as the head of protocol. In those moments of excitement, the head of protocol of India, Mahbub Khan, was beside me. He is the one who had informed me about our itinerary some time before Bangabandhu’s landing in Palam Airport. We were supposed to go to Kolkata from Delhi that morning. Bangabandhu was supposed to deliver a speech in Kolkata in the afternoon. Then we were supposed to go to Dhaka from Kolkata, where the first rally of Bangabandhu in Bangladesh was scheduled for that same afternoon. Mahbub Khan informed that we would travel from Delhi in the government aircraft of the Indian president, “Rajhongsho”, instead of travelling in the British Comet. Our luggage was kept in the “Rajhongsho” before Bangabandhu’s flight landed from London. Mahbub Khan informed us that the luggage of Bangabandhu and of the people accompanying him will be transferred to “Rajhongsho” as soon as the British Comet arrives with them. He said the responsibility of this procedure will be his.

Bangabandhu and Prime Minister Indira Gandhi went for a private meeting in the presidential building, right after the rally. We, the attendants, were being served samosas, kebabs, and hot cups of tea and coffee on silver trays by the waiters in a decorated hall right beside. Suddenly, my colleague Mahbub Khan was summoned into the room where Bangabandhu and Prime Minister Indira Gandhi were having their private meeting. Sometime later, Mahbub Khan hurried out of the room and said, “My dear colleagues! Our itinerary has changed. Everything has changed. You are not going to Kolkata anymore. You will head straight to Dhaka and that too, not in the “Rajhongsho” but in the British Comet.” Then he said that we had no reason to worry. He would instruct the designated employees at the airport right away about transporting our luggage from “Rajhongsho” to the British Comet and that in the meantime, he would send a message about this to Dhaka and Kolkata. I had only one responsibility which was to ascertain by communicating with Sir Terence Garvey, the British High Commissioner in Delhi, via telephone, if the British Comet will be successful in landing in the runway of the Dhaka Airport which was damaged by war. Though he got to know from his sources that it was possible, it was good to be more careful. It would have been good for me to know directly. I had known the British High Commissioner, Sir Terence Garvey, for a long time. Back in the early ’60s, when he was the counsellor of the British Embassy to Beijing, I was the Second Secretary of the Pakistan Embassy there. He had established contact with me at Ashok Hotel after seeing my name in the newspaper among the Bangladesh delegation, headed by Foreign Minister Abdus Samad Azad on December 6. Though Britain still had not given any recognition to Bangladesh and we had no idea about Bangabandhu’s immediate release on December 7, still, Terence Garvey came to meet me in my room that day and discussed about the war situation of Bangladesh.

I instantly contacted Sir Terence Garvey via telephone upon Mahbub Khan’s request. He assured me that it was totally safe for the Comet to land on Dhaka Airport’s runway.

I had heard about the reasons for changing the decision from Bangabandhu while on the plane. I heard that the schedule for the Kolkata journey had been changed for three reasons. Bangabandhu wished to return to his country’s people the first chance he got. Secondly, if there was a delay in Kolkata somehow, it would be impossible to hold a rally in Dhaka during a winter evening, since the electricity supply in Dhaka was unreliable. Thirdly, during the struggle for independence, inhabitants of West Bengal and Kolkata had given shelter to lakhs of Bangladeshis. According to Bangabandhu, instead of thanking them during the break between their journey, it would be better to go on a special Kolkata tour to express our gratitude to them.

Why was the Indian President’s plane “Rajhongsho” not used for this journey from Delhi to Dhaka?

According to Bangabandhu, it would not have been prudent to have changed planes midway since the British government had so courteously sent a special plane.

While returning to Dhaka with Bangabandhu on that pleasant afternoon, I had realised that as the head of protocol I had a lot to learn about diplomacy and diplomatic norms from the new President.

Anyway, during that wonderful morning, we were on the way to Dhaka.

“Who is this?” he suddenly asked while pointing at me, as I was unfamiliar to him. Foreign Minister Abdus Samad Azad took my name and told him that I was the one who wrote his speech.

“He has written what is on my mind,” said Bangabandhu.

My historically conscious mind was shaken by his words. I took out his speech from my pocket and handed it to him. “As a memento, I would like your signature on the speech,” I said.

“Of course. Hand me a pen,” he said.

The speech signed by Sheikh Mujibur Rahman is still in my possession. It carries very fond memories of him. I also have the page dated January 10, 1972, from my diary. I had handed him that as well. My diary’s page had one incredible name scrawled all over it – Sheikh Mujib. Clear, unwavering, and everlasting.

The Bangladeshi passengers on the plane were Abdus Samad Azad, Kamal Hossain along with his family, Maula, journalist Ataus Samad and me. Bangabandhu inquired about many of his known ones. His remarkable memory allowed him to remember the name, occupation, age, location, and incidents relating to everyone. I remember much of what he said, but have also forgotten a lot of it.

My diary’s page dated January 10 is filled with his signature. The page for that day no longer had any space for me to write on. Due to the busy days that followed Bangabandhu’s return to Dhaka, there was no time for me to keep writing in my diary.

He spent most of his time on the plane chatting with Foreign Minister Abdus Samad Azad. I remember Ataus Samad, whom he knew well, was talking to him eloquently, as is characteristic of journalists. Kamal Hossain and Maula had joined me in the audience. I remember a few things. He asked about how to change the national flag bearing the country’s map.

It was said that the interim Prime Minister Tajuddin might have taken some primary steps regarding this issue. He had discussed this issue with Chhatra League leaders.

The national anthem? The fact that this beautiful, famous song’s melody does not pull on the heartstrings. But we still have to accept it. The song carries the bloody memories of lakhs of martyrs.

And the government? It should be parliamentary, democratic Bangladesh.

Faruq Choudhury was a former Foreign Secretary of Bangladesh Government.

This excerpt is taken from Faruq Choudhury’s autobiography Jiboner Balukabelay (Prothoma Prokashan, 2014)

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments