Why are we missing out on global FDI opportunities?

Empirical evidence globally suggests that foreign direct investment (FDI), when used strategically and combined with supportive policies, can facilitate economic growth. Recent examples of countries that have prospered from a strong FDI role include Korea, China, Malaysia, Singapore, Indonesia, and Vietnam. The role of FDI has been more muted in South Asia. More recently, India has been gaining global FDI attention. FDI provides multiple benefits, including capital formation, technology transfer, opportunities for skill upgrading, and better access to global markets. The quality of FDI is as important as its quantity. Thus, FDI that is export-oriented is much more effective for boosting development compared to enclave-type FDI in mining.

Over the longer term, the global supply of FDI has prospered, rising from $204 billion in 1990 to a peak of $2,049 billion in 2015, before decelerating to $1,331 billion in 2023. The pace of increase in FDI flows for developing countries has been even more remarkable, accelerating from a mere $33 billion in 1990 to $889 billion in 2021. There has been a slight decline since then to $867 billion in 2023.

Much of the FDI flows to developing countries have concentrated on countries like China, Singapore, Brazil, Mexico, India, Indonesia, and Vietnam. Bangladesh has made repeated efforts to court higher FDI, yet the track record is poor. It reached a peak of $3.6 billion in 2018 and has basically fluctuated between $2-3 billion per year. The latest FDI position of Bangladesh, compared with the developing world's more dynamic economies, is illustrated in Figure 1.

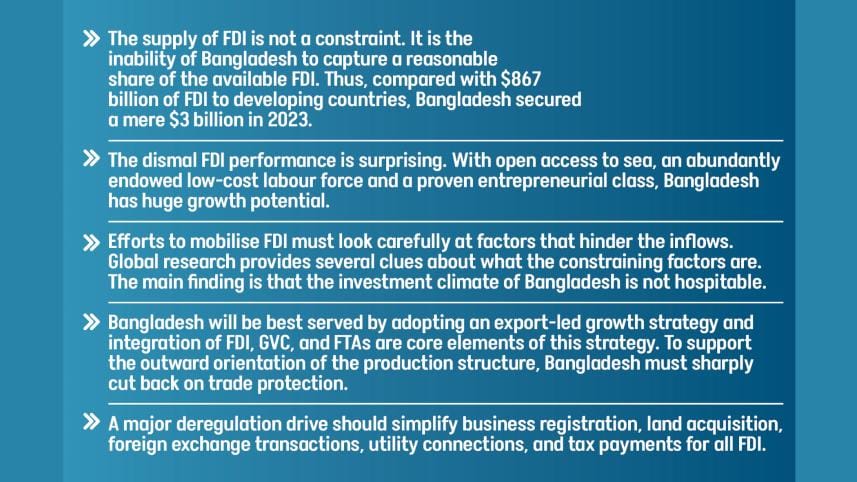

Clearly, despite a downturn in global FDI flows, the supply of FDI to developing countries has been relatively robust, exhibiting a rising share of developing countries in total global FDI flows. So, the supply of FDI is not a constraint. It is the inability of Bangladesh to capture a reasonable share of the available FDI. Thus, compared with $867 billion of FDI to developing countries, Bangladesh secured a mere $3 billion in 2023. This is almost a drop in the large FDI bucket.

The dismal FDI performance is surprising. With open access to the sea, an abundantly endowed low-cost labour force, and a proven entrepreneurial class, Bangladesh has huge growth potential. The growth value of these features is demonstrated by the major successes in the exports of ready-made garments (RMG) and foreign remittance earnings. Yet the benefits of these advantages seem to have localised in the areas of exports of RMG and low-skilled labour only. They have been stunted in the matter of export diversification and the attraction of FDI.

Efforts to mobilise FDI must carefully examine the factors that hinder inflows. Global research provides several clues about what the constraining factors are. The main finding is that the investment climate of Bangladesh is not hospitable. Global rankings of investment climates conducted by the World Bank and the World Economic Forum place Bangladesh in the bottom 25 percent of countries ranked, much below the rankings for Singapore, China, Indonesia, Malaysia, India, and Vietnam.

The major constraints that hamper FDI include high transaction costs related to securing investment permits, obtaining land, getting electricity, paying taxes, cross-border trading, restrictive foreign exchange policies, enforcing contracts, securing skills, and weak infrastructure. More recently, a sharp deterioration in law and order and political uncertainties have become binding constraints.

The investment climate-strengthening agenda is large and will require sustained reforms over the medium to long term. There are no quick fixes, but a start can be made by setting priorities. The best approach would be to learn and adapt from the good practice example of Vietnam. Research shows that several factors contributed to growing FDI inflows in Vietnam.

First and foremost, Vietnam adopted an export-led growth strategy since the early days of adopting the "Doi Moi" (Renovation) reform programme in 1986. Since then, Vietnam has shown unwavering commitment to implementing this export-led growth strategy. Commensurate with this, Vietnam integrated the attraction of FDI, participation in Global Value Chains (GVC), and free trade agreements (FTAs) as core elements. Thus, FDI became an integral part of its growth strategy and not an afterthought.

Secondly, policies, investments, and institutions were adapted appropriately to pursue this strategy progressively.

Finally, Vietnam focused strong attention on political stability, law and order, and policy consistency. It gets high marks on all three aspects, which has greatly facilitated FDI inflows.

On the policy front, core policy reforms included:

1) Trade liberalisation: Vietnam recognised that the successful pursuit of an export-led growth strategy can only co-exist with a trade policy that lowered trade restrictions and avoided trade policy-related anti-export bias. Accordingly, most export restrictions were removed, and import duties were cut. Consequently, Vietnam has one of the most liberal trade policy regimes in the developing world.

2) Liberal foreign investment policy: Vietnam adopted a very liberal foreign investment policy, welcoming foreign investment in all sectors of the economy (agriculture, manufacturing, construction, and services). It took comprehensive regulatory reforms to improve all aspects of the investment climate for foreign investment, including business clearances, land acquisition, utility connections, foreign exchange transactions, and paying taxes.

3) Sound macroeconomic management: Vietnam took strong measures at early stages to stabilise the macroeconomy and took steps to preserve macroeconomic stability throughout the development process.

4) Proper exchange rate management: Vietnam recognised the importance of proper export incentives by maintaining a flexible exchange rate and avoiding sharp appreciation in real terms.

5) Improving trade logistics: Vietnam invested strongly in infrastructure (especially seaport container terminals) and reformed trade facilitation institutions. As a result, there was substantial improvement in all areas of trade logistics, including customs clearances, port facilities, power supply, and inland transport.

6) Importance of participating in Global Value Chains: Vietnam rapidly integrated into the global production process by participating in global value chains (GVC). This strategy, by itself, unleashed huge FDI inflows. Vietnam's entry into GVC was strategic and targeted the hugely prospective electronics market, which reached an estimated global export value of $2.5 trillion in 2023. Vietnam is now a leading manufacturer and exporter of electronics, and in 2023 it was ranked as the 10th largest exporter of electronics, with an estimated value of $142 billion.

7) Strengthening innovation and technology adoption: Vietnam's strategic decision to enter the global electronics market was supported with a policy drive to strengthen innovation and technology. While much of the production and exports in high-tech industries are based on FDI, domestic capabilities are being built up. Investment in R&D is picking up steam to support innovation and technology development, the skill base is improving through large investments in education and training, and a strong focus on ICT is enhancing knowledge acquisition, knowledge transfer, skill development, and labour productivity.

8) Strengthening human capital and skills development: Vietnam scaled up its human development programme through large public investments in health, education, training, and social protection. Vietnam spends a massive 12 percent of GDP on human development, compared to 3-4 percent of GDP by Bangladesh. Progress on the human capital front has made it possible for Vietnam to rapidly train and deploy its labour force to work with multinational companies to acquire technology and high-end skills. Implications for Bangladesh FDI strategy and policies: The lessons for Bangladesh are clear. Bangladesh will be best served by adopting an export-led growth strategy, with the integration of FDI, GVC, and FTAs as core elements of this strategy. To support the outward orientation of the production structure, Bangladesh must sharply cut back on trade protection. It must welcome FDI in all sectors, while focusing especially on export-oriented FDI. A major deregulation drive should simplify business registration, land acquisition, foreign exchange transactions, utility connections, and tax payments for all FDI.

Bangladesh must take all steps to stabilise the macroeconomy, focusing on fiscal reforms that collect more revenues from the taxation of income and profits from state-owned enterprises and sharply cut back reliance on trade taxes. Trade logistics costs must be lowered in line with good practice countries through customs and port clearance deregulation, document digitisation, and investments in multimodal transport infrastructure. Investments in R&D and ICT should be used to upgrade innovation and technology adaptation capabilities.

A strong focus on education and training is necessary to take full advantage of the abundant labour force that presently suffers from low education and low employable skills. Public spending on education and training must be increased to at least 4 percent of GDP over the next 5 years. Partnership with the private sector in imparting training programmes, including on-the-job training, will need to be a core component of the training programme.

Restoration of law and order and political stability are sine qua non for any sustainable FDI drive. Without a strong push in these areas, it will be very difficult to attract higher FDI into Bangladesh.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments