The root of the financial corruption

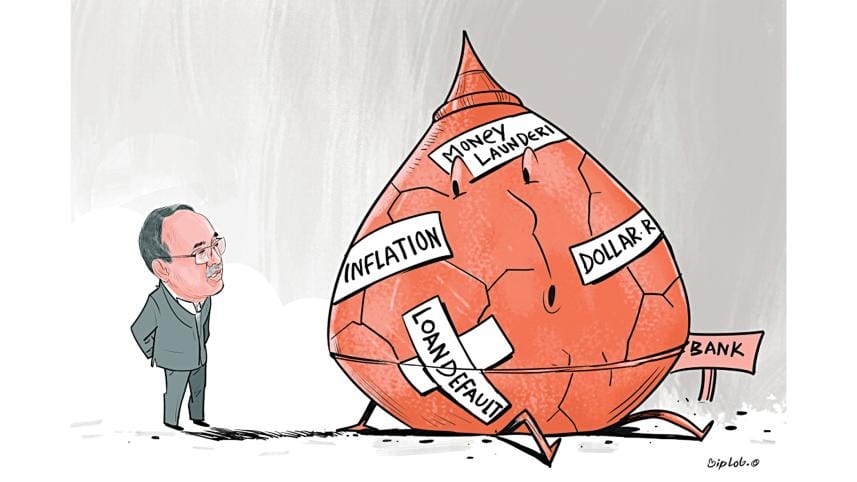

One of Benjamin Franklin's quotes states, "Creditors have better memories than debtors." But the inverse is true in Bangladesh, where the creditors often intentionally suffer from amnesia. Their inefficiency and malpractice have made the culture of defaulting by debtors a state-of-the-art bonanza in the country. The miseries of Bangladesh's financial sector are attributable to the rent-seeking behaviour of politicians who use the sector for personal pecuniary gains.

Bangladesh's banking sector and capital market have been ruthlessly plundered by the same group of oligarchs who have grown like parasites with the regime. Rarely will anyone find a country where the share of distressed loans amounts to 30-40 percent of total outstanding loans. That is the biggest vulnerability of Bangladesh's financial sector, warranting urgent reforms.

Forty-three private commercial banks, six state-owned commercial banks, three specialised banks, nine foreign banks, and one digital bank make up the total of 62 banks in Bangladesh. The regimes have always let banks mushroom not to promote competition but to fuel the growth of a handful of oligarchs who can sponsor the party in power. The banks in Bangladesh have grown in an unhealthy way, populating the financial landscape just like village-based grocery shops. This has developed cracks in the financial system, where institutions are fragile, inept, and susceptible to disasters.

According to World Bank data for GDP in 2023 at constant 2015 prices, Bangladesh's GDP was $323.28 billion, Pakistan's $400.17 billion, and India's $3,199.06 billion. Hence, Pakistan's GDP was 1.24 times larger than Bangladesh's, while the number of banks in Pakistan amounted to 41 compared to 62 in Bangladesh. India's economy was 9.9 times larger than Bangladesh's, yet India had only 33 banks. This indicates that the number of banks in Bangladesh is simply too high. India and Pakistan have increased the number of branches of existing big banks, which should have been the strategy for bringing banking services to the common people.

The licenses for new banks were not distributed to promote competition but to create monopolies. For example, only one Chattogram-based family controls as many as seven banks—something unprecedented in comparable countries. The oligarchs have kept opening banks one after another to continue plundering assets—a practice deeply endorsed by the politicians in power, particularly during the 15 years of the Awami League regime. Sometimes, tycoons used cash from one bank to buy another, then emptied another for money laundering.

Bangladesh Bank Governor Dr Ahsan Mansur stated that almost $17 billion was laundered overseas during the last 15 years, with a Chattogram-based family alone looting $10 billion. At least 10 banks are now suffering from a liquidity crisis, and Bangladesh Bank has printed Tk 225 billion to provide them liquidity support. The failure of liquidity management is another vulnerability that can cause bank runs—a progressive collapse of banks when customers withdraw deposits after losing confidence.

The default loans are akin to a broken roof for Bangladesh because of four reasons: 1) the actual amount of distressed loans is much higher than recorded; 2) the beneficiaries of these defaulted loans are mostly the bank owners; 3) the unconscionable tardiness of the judiciary acts as a haven for defaulters; and 4) the parliament, being a club of business tycoons, indulges the default culture that benefits corrupt politicians. This default culture is the killer of the financial industry and is more pronounced in Bangladesh than in comparable countries.

The big defaulters were allowed to restructure their loans in 2015—a provision that disproportionately favoured major delinquents. The finance minister during the 2019-2023 period loosened the definition of default loans, allowing them to be renamed "regular loans" by adjusting as little as 5 percent of the total defaulted amount. The default culture worsened when the government appointed two former bureaucrats as governors in 2016 and 2022. This marked a sharp deterioration in the institutional quality of the central bank, which requires scholarly leadership to control inflation and promote employment.

The total amount of outstanding loans rose to Tk 16.43 trillion in August 2024. Bangladesh Bank data shows that the share of default loans reached 16.93 percent in September 2024. However, it could be as high as 25-30 percent, as the Bangladesh Bank governor asserted. The situation worsened under the leadership of the two bureaucrat-turned-governors. If the financial sector's leadership is inept and unfit, the economy cannot expect any meaningful development for any of the stakeholders.

The amount of defaulted loans is estimated to be no less than Tk 4 trillion if the governor's assessment is considered. The IMF's assessment aligns with this figure, while the White Paper Committee estimates it at around Tk 6.75 trillion. Regardless of the exact figure, the entire banking sector appears doomed. The financial industry has been looted by a handful of financial hooligans, who have laundered a substantial portion of the money overseas.

The country has entered an inescapable trap, termed the "Devil's Triangle," formed by loan defaulters, tax dodgers, and fund traffickers. When a tycoon shows a loss in the income statement of his business, it enables him to avoid repaying bank loans and dodge taxes. Since he has money stashed away, he feels safe laundering it overseas. Thus, the same group of people occupies the three corners of the Devil's Triangle, with corrupt politicians at its centre.

The financial sector's primary objective is to finance consumption and investment for households and the government. While long-term capital should be raised from the capital market by issuing stocks, businessmen resort to using the banking sector, which is meant for short-term working capital. Banks must return savers' deposits on demand, making banking capital suitable for short-term support. However, businessmen often take long-term loans from banks, motivated by incentives to default and siphon funds abroad—something that cannot be done through the capital market due to accountability to shareholders.

This perversion has rendered both the capital market and banking sector largely dysfunctional. Two major stock market disasters occurred in 1996 and 2010. The culprits were rewarded with ministerial powers instead of punishment, creating moral hazards in the capital market. Over the 2018-2022 period, Bangladesh's market capitalisation averaged only 20 percent, compared to 97 percent for India. The Dhaka Stock Exchange index rose to 7,266 in August 2021 but gradually fell to around 5,000 by the end of 2024, indicating a loss of stakeholder confidence.

The discussion on reforms may be even simpler if we just consider correcting the misdeeds and malpractices that took place in both the capital market and the banking sector. The main tasks of reform should include the following actions:

1) Identifying troubled banks and reducing their number through consolidation or mergers.

2) Redefining default loans according to global standards.

3) Discouraging large loans to big industries and encouraging them to access the capital market.

4) Authorising the central bank and securities exchange commission to exercise magisterial powers for quicker resolution of default-loan cases and stock market irregularities.

5) Restructuring bank boards by engaging professionals and experts.

6) Limiting the number of directors from each family and reducing their tenures.

7) Making the banking sector a supportive vehicle for small and medium enterprises to generate wider employment.

8) Introducing laws holding financial institutions accountable for ensuring macroeconomic stability.

Bangladesh's financial sector must be brought back to stability and dynamism by combating corruption and irregularities that primarily originate from wealth-greedy politicians in power. The problems with the financial industry in Bangladesh are mainly institutional and political, not strictly economic.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments