Addressing the crisis in employment generation

In the third quarter of 2024 (July-September), the rate of unemployment in Bangladesh rose to 4.49 percent from 4.07 percent during the same period of 2023 (The Daily Star, January 6, 2025). In December 2024, the rates were 4.9 percent for Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) countries, 5.9 percent for the EU countries and 4.1 percent in the US. And policymakers in those countries are quite happy that unemployment rates have remained at such (read: "low") levels despite two years of inflation fighting by raising interest rates. So, why am I using the word crisis in the title of this article?

In view of the definitional/measurement issues regarding unemployment (i.e., whether a person has worked at least one hour in the week prior to the survey), it is necessary to look at other indicators to understand what is going on in the labour market. Also, it is important to put the whole issue in the context of what is happening in the economy as a whole—especially with respect to investment and growth. And if one does that, one gets a sense of crisis looming there.

Even though official data (especially on GDP growth) of the previous regime painted an unduly rosy picture of the economy, one can say that there was an acceleration in growth over the decades and growth has been reasonably high. And yet, employment growth was low and falling. We have been warning for some time that the economy was experiencing jobless growth. And now with the closure of many factories and lay-off of workers, the situation has worsened. With the adoption of contractionary monetary policies, and slowing down of investment amidst the current uncertainties, the prospect of job growth appears to be rather bleak.

Economic growth should enable people to move from agriculture and other traditional sectors to modern sectors, especially to manufacturing and modern services where productivity and earnings can be higher. This is how economic growth benefits people—through better jobs and higher incomes. But recent data show some worrisome trends. Although the process mentioned above had started, there has been a reversal in recent years. Several aspects of this reversal warrant attention.

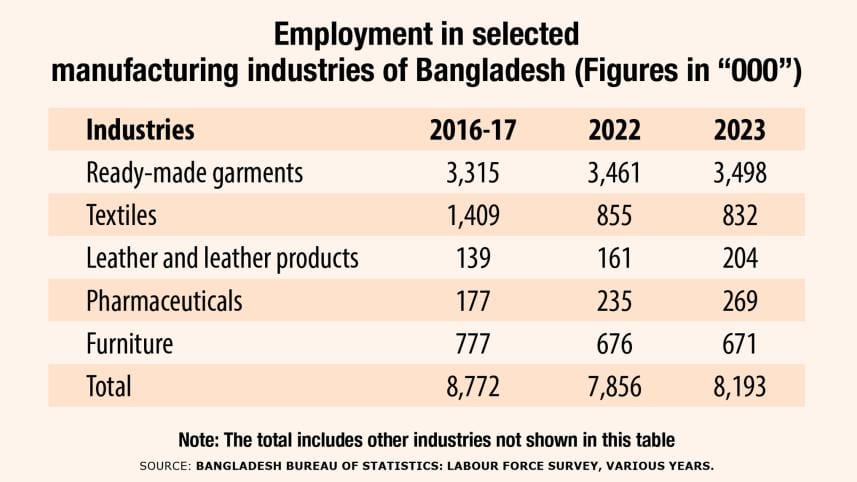

First, the share of agriculture in employment started rising instead of falling. Second, the share of manufacturing has started to decline. In fact, between 2016 and 2023, the absolute number employed in manufacturing declined from a little over 88 lakh to about 82 lakh (Table 1). The number employed in the ready-made garment industry increased by a paltry 183,000 in seven years. And the number of women in the industry is falling. Quite clearly, the economy has not only failed to continue its structural transformation, there is a tendency towards premature de-industrialisation.

One indicator of the failure of the economy to generate good jobs is the continuation of a huge proportion (almost 85 percent) of the labour force in informal sector and in informal jobs within the formal sector. Most of these jobs are characterised by low productivity, low income and absence of any social protection for those engaged in them.

Likewise, migration for jobs abroad is also an indicator of the failure of the economy to generate jobs in the country.

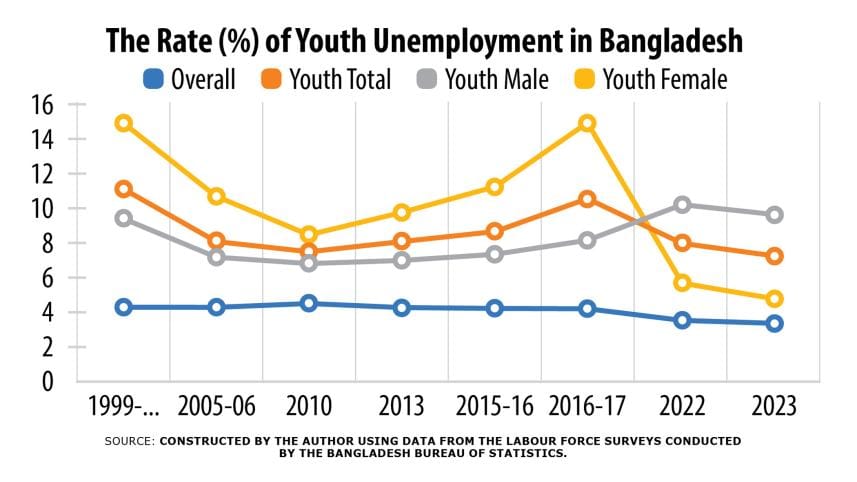

Unemployment among the youth is a major issue. It is not only much higher than overall unemployment but has been rising since 2010 (Figure 1). The rise is particularly noticeable for young men. The improvement seen in 2022 and 2023 is misleading because that is entirely due to the fall in the case of women which in turn can be explained by a big rise in own-account work. There has not been any real improvement in the overall employment situation of the youth. So, the frustration and discontent among them is easily understandable.

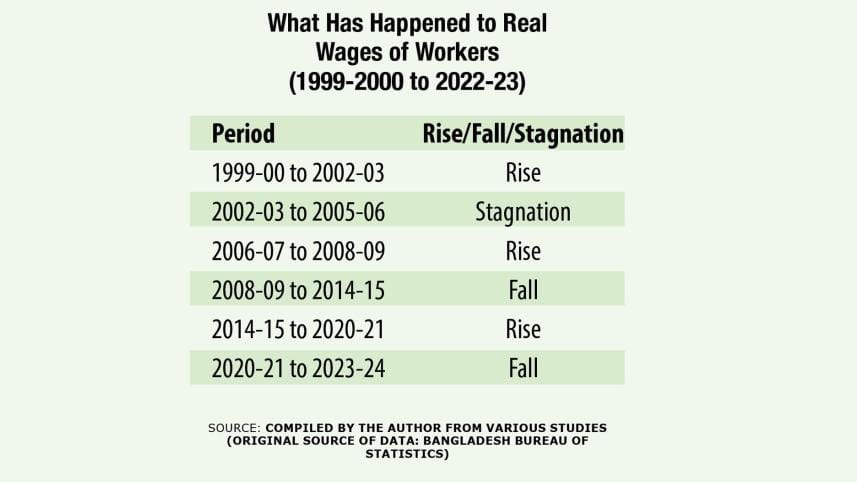

Another indicator of the crisis in the labour market is the trend in real wages (Table 2). Although real wages of workers are expected to rise as an economy attains economic growth, this has not happened in Bangladesh on a sustained basis. Real wages did rise during certain periods but the trend has not been sustained.

They fell during 2008-09 to 2014-15 when economic growth accelerated, and have been falling again for the last three years since 2022. Quite clearly, the benefits of growth have not been shared equitably.

The crisis in employment generation is not something that has hit us today. It has been in the making for years and decades. Policymakers usually consider employment to be an automatic outcome of economic growth and consider it unnecessary to have policies for that. The best that could be seen in official documents are perfunctory mentions of the issue or very rough projections to be forgotten later.

Employment is linked to output which in turn needs investment. But the current environment with all its uncertainties is not conducive to investment. The situation has been made more difficult by a restrictive monetary policy. Increases in interest rate were ostensibly aimed at fighting inflation. While macroeconomic stability is regarded as essential for economic growth, it is important to balance considerations of stability with those of investment, output, and employment. In fighting inflation, the real challenge before policymakers is to balance these considerations and to steer the economy towards a soft landing rather than crash landing. In other words, the aim should be to attain stability without choking investment, growth, and employment.

In the short run, the first thing to do would be to restore investors' confidence by taking decisive steps to improve the law-and-order situation and the industrial relations environment—the latter through effective tripartite consultations.

But experience shows that economic growth does not automatically guarantee employment growth. Productive employment can result from growth in sectors that create jobs with high productivity. From that point of view, growth of manufacturing and modern services is important. Within manufacturing, it is labour intensive industries that generate jobs in large number. In Bangladesh, the start was promising with the growth of the ready-made garment industry. However, the process remained confined to this single industry where employment growth has declined sharply in recent years. Although the country has potentials for other labour-intensive export-oriented industries like leather and non-leather shoes, electronics, furniture, etc., policymaking has never addressed the issue properly. Unifying the incentive structure is essential so that one single industry does not become too much more attractive for investment. Fiscal, trade, and industrialisation policies need to be applied in an integrated manner to create an attractive environment for all export-oriented labour-intensive industries.

High rate of youth unemployment is caused by a variety of factors including paucity of jobs compared to the number of job-seekers, difficulties in transition from the world of learning to the world of work, mismatch between qualifications possessed by job-seekers and those required by potential employers, difficulties faced in starting own business, and so on. While the availability of jobs is dependent on the rate and pattern of growth and can be influenced by macroeconomic and sectoral policies, special attention needs to be given to the other issues mentioned above. And that is best done through targeted programmes for assisting young job-seekers. There are examples of "good practices" on this from where ideas can be drawn.

One well-known instrument for addressing the employment challenge in countries like Bangladesh is direct employment generation programmes. They usually generate employment in infrastructure—especially at the local level where labour-intensive methods can be used. The concept can be broadened to cover other sectors also. Bangladesh has experience in such programmes which can be revived with appropriate modifications to suit the current situation and requirements.

A major issue with respect to the employment challenge in Bangladesh is the mismatch between qualifications and skills required and what job-seekers possess. There are several issues here that have been the subject of discussion for a long time. First, as the economy moves to higher levels, the emphasis should shift towards increasingly higher levels of education and technical education. Second, whether job-specific skills are to be imparted by educational and training institutions or through alternative means, e.g., enterprise-based training is a subject that can be debated. Third, there is the question of who pays for training. Should the government alone be responsible or enterprises should also bear at least part of the costs is an issue that needs to be discussed.

In sum, addressing the employment crisis requires integrated action on a wide front. What is important is to recognise the seriousness of the problem and the political will to address it accordingly.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments