Restructure local governance from a presidential to a parliamentary system

The Daily Star (TDS): What are the commission's core recommendations for reforming local government?

Tofail Ahmed (TA): Comprehensive reforms require time, but certain critical areas, particularly the legal and structural framework of local governance, demand immediate attention. In the past, even less-educated local chairmen and members maintained ethical standards, with limited funds keeping corruption in check. However, in the post-independence period, credibility declined, and corruption became more widespread. This has resulted in an increasingly centralised, single-person (Chairman or Mayor)-dominated administration, with mayors making decisions without formal council meetings. Dhaka City Corporation, for instance, rarely held discussions for years, and councillors often passively accepted decisions for personal gain. Large-scale projects funded by the ADB and WB are poorly planned, leading to mismanagement and wasted resources due to city corporations' lack of capacity to manage these projects once completed.

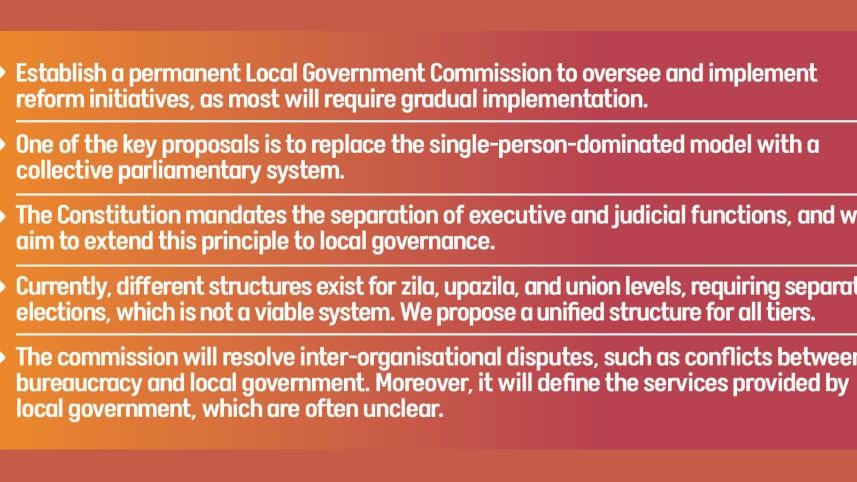

Given these challenges, our report presents concrete recommendations, particularly where urgent reforms are necessary. One key proposal is to establish a permanent Local Government Commission to oversee and implement reform initiatives, as most will require gradual implementation.

An immediate reform is restructuring local governance from a presidential to a parliamentary system, ensuring participatory decision-making and collective leadership. Currently, councillors lack authority, discouraging capable individuals from these roles. Empowering them to elect the Chairman or Mayor would attract more qualified candidates. This will also indirectly incentivise competent individuals, creating a natural progression—those aspiring to become mayors would first serve as councillors, fostering leadership development at the grassroots level.

We also propose allowing government employees to contest local elections, provided they do not assume chairman role, as it requires full-time commitment. However, structural changes alone are insufficient—political culture must also evolve. While a commission report cannot achieve this immediately, it must establish a process that initiates lasting cultural change.

Local government currently operates in a de facto system, where many practices persist as traditions rather than legal mandates (de jure system). For example, in Union and Upazila Parishads and City Corporations, project budgets are often distributed among members who act as both contractors and implementers, despite this not being legally sanctioned. Instead, budget allocations should be based on strategic planning, ensuring funds are used for specific initiatives rather than individual discretion.

One of the key proposals is to replace the single-person-dominated model with a collective parliamentary system. In the current Union Parishad (UP) structure, a legislative system is absent. We propose a separate legislative body comprising all elected members, led by a Sabhadhipati, who will function as a council moderator. Decisions made by this body will be implemented by the executive body, consisting of the Chairman, executive officers, and field extension staff. Ensuring that the Sabhadhipati leads council meetings is essential to prevent undue influence from the Chairman. This model should be extended to all levels, including Upazila, Union, and City Corporations, to ensure more accountable governance.

Under this framework, the legislative council will deliberate and make decisions, the executive body will implement them, and the legislative wing—through standing committees—will provide oversight and feedback. Currently, standing committees exist in name only, but under our proposed system, they would function as active, full-time oversight bodies. Additionally, a secretary would be appointed to support committee operations, a role that was previously absent. Moreover, the parliamentary system will facilitate debates among equal candidates competing in elections.

Another key reform is the removal of judicial responsibilities from the UP. Instead of the existing Village Court (Gram Adalat) system, we propose a structured legal framework comprising a Civil Court, a Criminal Court, and an ADR (Alternative Dispute Resolution) Magistrate to oversee Salishi practices. The Constitution mandates the separation of executive and judicial functions, and we aim to extend this principle to local governance. Regional disputes would be resolved through formal judicial processes rather than by a politically appointed chairman. Removing Village Court duties from the UP will allow for a greater focus on governance, reinforcing cultural change. Under the new system, the rule of law will be firmly established, preventing chairmen from passing verdicts at their discretion in regional disputes.

Additionally, we propose expanding UP staff by adding five to six administrative personnel while maintaining the current number of village police officers. Each upazila-level officer should oversee a specific Union—not for administration but for guidance and monitoring. They would attend legislative council meetings to ensure proper governance.

Council meetings should consider all opinions while maintaining agendas and making informed decisions. These reforms require training and gradual cultural adaptation.

TDS: What challenges do you foresee in transitioning from a presidential-style local governance system to a parliamentary-style system, and how can these challenges be addressed?

TA: The first challenge is the reluctance of former Chairmen or Mayors to accept this new system, along with resistance from higher-level officials. However, members, councillors, and civil society representatives, who form the majority, support the proposed model. Political parties also hold differing views, adding complexity.

Another concern is the potential for vote manipulation in the Chairman election. In a 15-member council, securing 7–8 votes unethically is possible. However, given the local nature of the election, such malpractice would likely be noticed by the community. To prevent this, any member found guilty of vote-buying or selling should lose their membership. Additionally, an affidavit with compliance conditions and penalties should be required.

Moreover, some may question why direct elections are not being implemented. The reason is to ensure broader participation through a two-phase voting system. This indirect election process prevents power from being concentrated in a few hands, promoting a more balanced distribution of authority.

TDS: What changes are proposed in the local government election system, particularly concerning women representatives?

DTA: Local government elections will be more efficient if the parliamentary system is implemented alongside a few legal amendments. Currently, different structures exist for zila, upazila, and union levels, requiring separate elections, which is not a viable system. We propose a unified structure for all tiers.

During elections, unions and paurashavas will follow a similar strategy. People will vote for the Zila Parishad (ZP) ward, which was previously not mandated. The number of wards under ZP will match the number of upazilas in that zila, with three wards per upazila. Similarly, there will be three wards per union under Upazila Parishad (UZP). If an upazila has 10 unions or a zila has 10 upazilas, both UZP and ZP will have 30 wards. This ward formation is solely for elections, not for other local government activities.

A voter at the union level will cast one vote for their UP ward and two to three votes for UZP and ZP wards, respectively, depending on the size. All three elections will be held on a single day with separate ballots, reducing costs. Through this streamlined process, the total budget for local government elections could be capped at BDT 600–700 crore.

Regarding women's representation, opinions are divided. A minority strongly advocates for eliminating reserved seats for women. However, from the perspective of many women, direct competition in elections remains challenging, making reserved seats necessary. That said, the current reservation system has proven largely ineffective.

We propose a rotational system for women's seat reservations across different wards, applicable for one term only. After serving in a reserved seat, female representatives must contest the next election like any other candidate. After three election cycles under this system, the fourth could be held without reservations as a trial, with the long-term goal of phasing them out.

TDS: Can you elaborate on the role and structure of the proposed permanent local government commission?

DTA: The recommendation for a permanent local government commission was consistently made by the previous three commissions led by Rahmat Ali, Nazmul Huda, and Shawkat Ali. However, they were not implemented. The Constitutional Reform Commission has already proposed a permanent commission with constitutional status for local government, reinforcing our recommendation.

The commission will resolve inter-organisational disputes, such as conflicts between bureaucracy and local government. Moreover, it will define the services provided by local government, which are often unclear. One such service is registration—birth and death registration, warisan (succession) certificates, and marriage registration—currently handled under the Ministry of Law. However, these should fall under the purview of local government.

Revenue generated from these services will be divided into three parts: one portion for the UP, the other two portions for the Marriage Registrar and the central government. However, all records and documents will be kept at the UP level, as divorce and other marital disputes will be resolved at the local level through the newly proposed judicial process.

Moreover, a household data system must be established, linked to NID and birth registration, to build a unified database. If implemented, the Election Commission (EC) could update the voter list within a single day. The EC, with its advanced server facilities, can provide technical support to the permanent commission in achieving this. Thus, comprehensive population data will be available to local government, and this database must be updated every three months by the permanent commission.

The permanent commission should also play a role in land management. It should maintain records on the types of land in each area, such as agricultural land, high or low land, water bodies, forests, and khas land. The commission must be consulted before khas lands, forests, or water bodies are used for any purpose.

Furthermore, there is currently a provision for tax exemption for those owning up to 25 bighas of land. However, we propose that land tax must be collected from all landowners. Every landowner should have a legal land registration document and be required to pay tax.

The commission must also oversee land transfer and pricing to ensure that each land parcel has a legally registered price reflecting its actual value. Revenue from this process will be divided between central and local government. At present, the land pricing system is highly flawed. Land is sold at one price, while a different price is recorded in the registration document. To eliminate this differential rate system, local government must assume responsibility for these matters.

TDS: How can local governments be better funded, and what steps should be taken to enhance their capacity?

DTA: We have several major recommendations for local government financing. Along with project financing, there must be a provision for 'tax sharing'. While the central government can retain a significant portion of tax revenues, it must allocate a share to local administrations, as taxes are collected from local sources. The exact proportion of tax sharing can be determined by the government, but it is crucial that a portion is distributed to local governments. Furthermore, VAT applies to all individuals, including those in rural areas. Therefore, a share of VAT revenue should also be allocated to local governments. For example, the central government could retain 70% of VAT and tax revenue, while 30% is shared among all local governments across Bangladesh.

This system of tax sharing would help align the National Development Plan with local development plans. The central government need not carry out all development activities itself; it can finance and delegate certain projects to regional governments, monitoring their implementation. It is essential that the national plan clearly defines which projects will be handled by the central government and which will be managed by local governments.

TDS: What mechanisms does the commission plan to recommend for institutionalising the reforms and ensuring their long-term sustainability, regardless of regime changes?

DTA: We cannot guarantee the implementation of all proposed reforms when there is a change in government. However, we are hopeful that the interim government will establish a comprehensive committee to thoroughly analyse our recommendations in consultation with political parties. Through consensus, they can implement the reforms that are immediately feasible, while those requiring more time can be addressed in the future.

To facilitate this process, we have proposed the establishment of a permanent commission to ensure that the implementation and detailing of our recommended reforms continue over time. Given the widespread recognition of inefficiencies in local government, there is strong momentum for reform. Since local government directly affects people across the country rather than just at the central level, nationwide engagement is expected.

The interview was taken by Miftahul Jannat.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments