Prioritising profits over the environment is costing us dearly

The Daily Star (TDS): How would you assess the current state of Bangladesh's environment, and what are the most pressing challenges?

Ainun Nishat (AN): We do not follow rules or obey regulations. Factories are set up indiscriminately, dumping liquid waste into nearby canals. Even wealthier residential areas contribute to pollution, with toilets directly connected to rivers, lakes, or canals. For instance, sanitary waste from Gulshan ends up in nearby lakes. Bangladesh lacks a proper sewer system. In Dhaka, Wasa treats only 5–10% of liquid waste at the Pagla sewage treatment plant, while the Dasherkandi Sewage Treatment Plant (STP) remains unconnected. The situation is absurd—like constructing a ten-storey building without installing an elevator or staircase. How would people use it? Similarly, pollution—whether soil or water—remains uncontrolled.

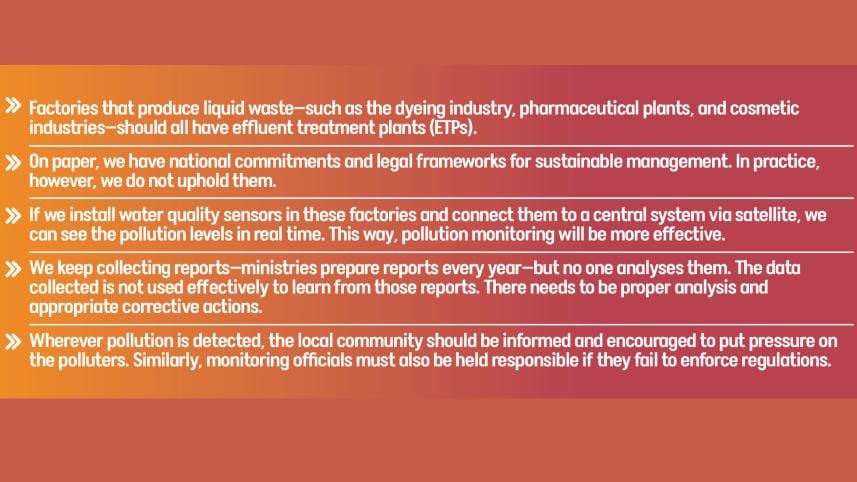

Yet, all the necessary laws are in place. Article 18A of the Constitution commits the country to protecting the environment, ecosystems, biodiversity, and wetlands. On paper, we have national commitments and legal frameworks for sustainable management. In practice, however, we do not uphold them. Wetlands are depleted, forests are cut down, and civic responsibility is lacking—both among businesses and communities in their daily activities and operations.

To illustrate this point, let me share an experience. During my visit to Tashkent, Uzbekistan, last year, our guide took us to various places, including a traditional local market that had existed for around 3,000 years and remained largely unchanged. It was a circular market, divided into seven sections. Despite having a fish section, there was no dirty water anywhere. The poultry section had properly processed chickens, neatly stored in refrigerators. Vegetables were displayed in an orderly manner. The market was even a tourist attraction, demonstrating how a well-maintained market should function.

Now, compare that to Bangladesh. If you visit a wet market here, you risk ruining your shoes—or even your trousers. Our behaviour is reckless and unhygienic. People litter, spit, and urinate anywhere. There is little awareness of the need to protect public property, water bodies, or the environment. Even breathing in our cities has become hazardous.

The poorest communities suffer the most from our environmental negligence. Many live in slums next to drains or canals. If these waterways were properly maintained, their homes wouldn't flood every rainy season. But since canals are encroached upon and clogged, water cannot drain, leaving their homes submerged. While lower-income groups also contribute to pollution, they do so out of necessity rather than choice. If our country were better managed and free from pollution across all sectors, their circumstances would improve as well.

TDS: Do you think our problem is a lack of awareness, or do we simply not care?

AN: It is not about awareness; rather, we are knowingly irresponsible. We understand what is wrong. However, the focus on maximising profits, often disregarding the long-term consequences for the environment, puts us at a disadvantage.

Monitoring is crucial. If you look at the garment factories now, many of them are becoming responsible. However, many factories—chemical factories, dyeing factories, and jeans factories—continue to pollute without following compliance regulations.

Take our leather industry, for example—it could have been the most important sector after garments since we produce a lot of raw leather. Bangladesh is capable of making high-quality processed leather goods with an abundance of raw materials and labour. But we are unable to export because our processed products do not meet environmental standards, which is a concern. The five or six leather industries that do manage to export succeed because these businesses comply with regulations and have their own effluent treatment plants (ETPs).

We have laws and regulations such as the Bangladesh Environment Conservation Act, 1995, and the Environment Conservation Rules, 1997, which mandate that every industry must have a wastewater treatment system. According to Regulation No. 94 of the Environmental Assessment Regulations 2012, ETPs are mandatory. But are they being implemented? No. As citizens, we have not fully grasped the importance of these regulations.

Factories that produce liquid waste—such as the dyeing industry, pharmaceutical plants, and cosmetic industries—should all have effluent treatment plants (ETPs). Now, garment industries have started implementing them because their buyers demand it. Similarly, some chemical companies, like Unilever, and shoe manufacturers, like Bata and Apex, who are involved in export markets, at least try to treat their waste.

But it is still insufficient because the number of export-oriented companies is small. The Export Processing Zones (EPZs) lack ETPs, as the foreign companies operating factories in these zones do so without ETPs.

We do have monitoring systems, but enforcement is weak. Moreover, the monitoring, evaluation, and learning processes are inadequate.

We already have sectoral policies in place for different industries—agriculture, fisheries, manufacturing. Every sector has guidelines. But the problem is that we do not comply with them. That is the core issue.

TDS: Bangladesh consistently records some of the worst air quality levels in the world, posing severe health risks. What urgent measures should be taken to combat this crisis?

AN: The government needs to take a stronger stance. The black smoke from vehicles, brick kilns, or improperly stored construction materials causes air pollution. They have no right to pollute the air.

There are four main sources of air pollution in Dhaka. Brick kilns are major polluters. Construction materials—where is the sand stored? Where is the cement kept? How are the bricks stored? If not handled properly, they contribute to dust pollution. Dust on city roads and vehicle emissions generate air pollution.

We know the causes. We need to implement solutions accordingly. Take Mirpur Ceramics, located next to the Mirpur Cantonment. It does not cause pollution. If it did, the cantonment authorities would take action. Mirpur Ceramics uses modern technology, and there are even better technologies available. Thus, technology is not even an issue here.

The brick kiln owners refuse to adopt advanced technologies because of the high initial investment. This again brings us to the fact that we are knowingly irresponsible. We understand everything, yet we do not act.

TDS: Plastic pollution is a major issue. What steps should we take to address it?

AN: Plastic and polythene are severely damaging our environment—rivers, coastal areas, and farmland are all suffering. We must stop this.

It is a matter of habit. I use a car, and in my car, I always keep reusable bags. When I shop, I use my own bag. People should carry reusable bags. The problem is with single-use plastic.

In Europe, if you ask for a shopping bag, they charge you one or two euros. That forces people to bring their own bags. The bag must be durable. In Bangladesh, our plastic bags are flimsy and non-durable. Plastic is not the issue—single-use plastic is. We need to enforce policies strictly.

You need a bottle to drink water? Just carry a small glass bottle. Now there are multiple options that nullify all the excuses. If people try a little bit, it can bring big changes.

In developed countries, waste is separated at the source. For example, households have four bins—one for plastic, one for paper, one for glass and metal, and one for organic waste. Paper waste, glass, and metal are all separated. Organic waste, such as kitchen scraps, is also disposed of separately. And the garbage collectors do not clean the streets daily—maybe once every two or three days. But waste is disposed of in an organised manner. This way, recycling becomes easier.

In Bangladesh, raw materials for recycling are collected at almost zero cost. Three to five years ago, Chinese businessmen were buying plastic bottles from Bangladesh and taking them to China. The recycling process was so profitable that they could afford to cover transportation costs from Bangladesh to China and still make a profit.

But we, as a nation, have a habit of arguing against anything beneficial. Instead of taking responsibility, we are always defensive without being proactive. Whenever a rule is introduced, we protest against it instead of following it.

Our garbage collection system is non-existent. A mayor once introduced tin trash bins in different areas, but people broke them. Disposal points were installed at street corners, but those too were misused. We do have two landfills—one in Aminbazar and one in Matuail. But in reality, we have 15–16 unofficial dumping sites. And if garbage is dumped without proper lining underneath, the leachate seeps into the ground, contaminating water sources. Everyone—the municipality, city corporations, and public health officials—knows this. Our problem is not a lack of knowledge. It is that our national character lacks discipline in practice.

TDS: What changes can be made to ensure that existing laws are properly enforced?

AN: Whether it is the garment industry, dyeing industry, leather industry, or chemical industry, they are all dumping untreated liquid waste into rivers, canals, and wetlands, polluting the water bodies. Now, let us assume that a factory owner has installed an Effluent Treatment Plant (ETP). But when an inspector arrives, they turn it on just for the inspection. Once the inspector leaves, they turn it off again.

We can monitor this in real time. If we install water quality sensors in these factories and connect them to a central system via satellite, we can see the pollution levels in real time. This way, pollution monitoring will be more effective.

The Department of Environment's staff should be held accountable. Wherever pollution is detected, the local community should be informed and encouraged to put pressure on the polluters. Similarly, monitoring officials must also be held responsible if they fail to enforce regulations. We must enforce monitoring, and based on that, evaluation must be conducted. Unfortunately, we stop at this point.

We keep collecting reports—ministries prepare reports every year—but no one analyses them. The data collected is not used effectively to learn from those reports. There needs to be proper analysis and appropriate corrective actions.

For example, if a factory is polluting, we should hold the owner accountable. If a brick kiln is causing pollution, we should enforce regulations on the kiln owner. If domestic pollution is a problem, we should engage local households in waste management. Globally, there is a strong emphasis on involving local communities and youth in environmental action.

TDS: How can local communities and youth contribute to positive environmental change?

AN: Take any village as an example. A union typically has nine wards. If you focus on just one ward, local elected representatives, school headmasters, madrasa principals, and mosque imams can all come together to form a community management committee.

Kitchen waste should be used to produce compost. Streets should be kept clean. People should be discouraged from littering—plastic bottles, paper, and other waste should not be thrown on the streets.

Globally, there is now a strong emphasis on locally led adaptation. If we keep our local water bodies and drainage systems clean and allow water to flow freely, there will be no waterlogging or flooding. Local efforts and empowered local representatives are essential.

The interview was taken by Saudia Afrin.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments