Missing policy reforms in Bangladesh’s transport sector

In a densely populated country like Bangladesh—especially in Dhaka, the mega city with its unique characteristics—addressing issues such as infrastructure, traffic control, and safety requires more than just physical development. This is a complex issue, and solely focusing on infrastructure will not provide a solution. Instead, comprehensive policy reform is essential. At present, significant loopholes exist in policy. We have not prioritised policy development, which is why, despite having infrastructure, we are not fully reaping its expected benefits.

Policy formulation and implementation are crucial for infrastructure development. When major transport infrastructure is built without policies for vehicle control, registration, or appropriate vehicle models, informal transport systems emerge. As a result, despite extensive infrastructure development, Dhaka has become an immobile city—something we experience daily. While a significant amount of infrastructure has already been constructed, the urgent need now is a policy on vehicle regulation and its effective implementation.

Dhaka already has strong connectivity with divisional and district cities. To enhance the public transport system, priority should now be given to selecting the appropriate types and numbers of vehicles. While the required investment is relatively low, the impact could be highly significant.

The current and future governments, along with policymakers, must recognise that investment should be distributed across divisions and districts rather than being concentrated in the capital. By developing workplaces in these areas, we can help decentralise economic opportunities and reduce the influx into Dhaka, ultimately reversing the trend of overpopulation in the city. Only then will we see a meaningful return on the infrastructure built over the past 15 to 20 years.

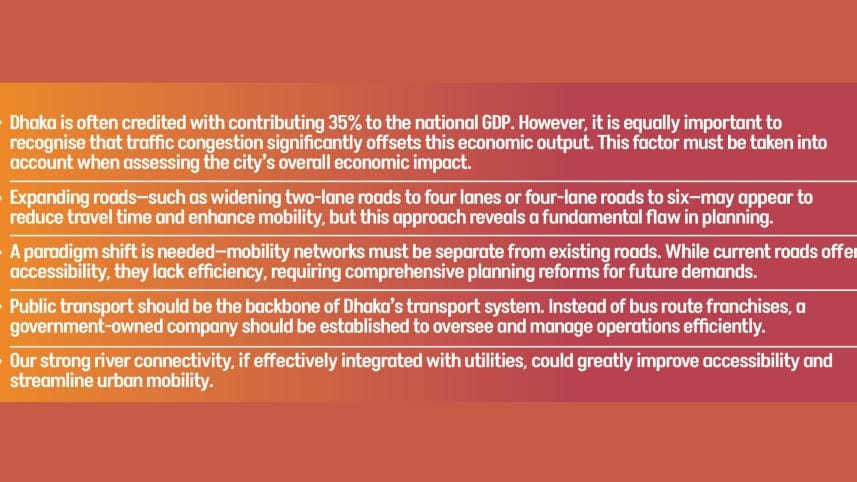

We often highlight that Dhaka contributes 35% to our GDP. However, it is equally important to acknowledge that this economic output is significantly offset by the costs associated with traffic congestion. This should be considered when evaluating the city's economic impact.

Additionally, the role of the Planning Commission is crucial. It must be strengthened, as it plays a vital role in shaping policies for both Dhaka and the entire country. Reforming the commission is necessary, particularly in how development projects are planned and approved, as this falls directly under its jurisdiction. At present, the commission lacks professional planners who have the expertise to assess whether a project will be truly beneficial. It is essential to include such professionals in the planning process to ensure that projects are effectively designed and yield long-term benefits.

Another critical issue is the strain on our road network, particularly regarding connectivity between Dhaka and other cities and districts. While it may seem that expanding roads—such as converting two-lane roads into four lanes or four-lane roads into six lanes—would reduce travel time and improve mobility, this approach exposes a fundamental flaw in planning. Roads such as the Dhaka-Sylhet Road or the Dhaka-Chattogram Road serve as connecting roads rather than dedicated mobility corridors. Even though widening these roads may provide temporary relief, the long-term impact will be minimal as they are not designed for sustained, efficient mobility.

The current approach to road development in surrounding areas, particularly road widening, often results in displacement and significant harm to local businesses. Moreover, expanding roads cannot be effectively managed by simply installing barricades, as these fail to address the strong social and economic ties between communities on both sides. For instance, despite barriers, people continue to cross the Dhaka-Mawa Expressway horizontally. This happens because these are connecting roads rather than dedicated mobility routes. Therefore, road planning must incorporate the development of a separate mobility network—an entirely distinct road system designed for improved transportation efficiency.

We need not look far for successful models; India has already implemented a solution with its Golden Quadrilateral, a separate mobility network with full access control. This network allows for speeds of 120 to 130 km per hour and is designed to minimise accidents by eliminating sudden access points. In contrast, merely widening existing roads in Bangladesh damages infrastructure, displaces communities, and fails to deliver sustainable improvements. This approach cannot be considered a viable solution for an effective mobility network.

A paradigm shift is needed—mobility networks must be separate from existing roads. While current roads offer accessibility, they lack efficiency, requiring comprehensive planning reforms for future demands.

Beyond improving the road system, Dhaka should be developed as a model city. Despite being the capital, it lacks a coherent structure. To address this, road infrastructure and transport-related projects must be kept free from political influence. The backbone of Dhaka's transport system should be public transport. Rather than relying on bus route franchises, a government-owned bus company should be established to oversee and manage operations effectively. This company would operate all buses, with the government responsible for purchasing and phasing out outdated vehicles. Existing private bus companies could become shareholders, with both public and private investment facilitating the introduction of new, modern buses. This approach would lead to a more sustainable mobility system. If we continue to rely on companies operating outdated buses, we risk perpetuating an inefficient and unsustainable transport model.

We have presented this proposal to Chief Adviser Dr Mohammad Yunus. While Dhaka has already established sufficient infrastructure, it is now crucial to create a new ecosystem for buses. This is not just about purchasing new buses and forming a company. All 4,000 existing buses in Dhaka should be upgraded, and a variety of new bus models should be introduced to enhance service quality. A unified transport company could be established to manage operations, ensuring better coordination and efficiency. Shareholders would benefit financially, while the government would maintain overall control, leading to an improved and more sustainable system.

Despite the complexity of mass transport in Dhaka, we have yet to establish a government-enlisted company to manage the system, even though we rely on such entities for linear metro or major infrastructure projects. That is why we have created a metro rail company and a BRT company, which currently operates only one line from Dhaka to Gazipur. However, Dhaka's bus system remains fragmented and inefficient. A comprehensive reform is necessary, ensuring that all buses operate under a single company for better functionality.

We are fortunate to have excellent river connectivity, which, if properly integrated with utilities, could significantly enhance accessibility and streamline urban mobility. A coordinated planning approach is essential, as water transport offers a sustainable, comfortable, and safe alternative with minimal environmental impact. However, development must not lead to further pollution or encroachment. While policies exist to prevent such damage, their strict implementation is necessary.

Dhaka's rail connectivity with other districts has long been discussed, particularly the commuter train system, yet little has been done to realise its potential. Kamalapur and the Airport should be developed as major railway hubs to strengthen connectivity and reduce pressure on roads. The railway sector must shift its focus from expansion to maintenance, ensuring that existing stations and services operate efficiently.

However, the most crucial reform needed is a shift in mindset. No country can achieve safe roads or resolve traffic congestion solely through infrastructure development—effective planning, policy implementation, and a change in public perception are equally essential.

This article was transcribed by Raisa Nanjiba.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments