Cultural interventions required to reform deep-rooted patriarchal norms

The Daily Star (TDS): After August 5, women and female coordinators of the movement appear to have gradually become less visible in initiatives and discussions. This raises an important question: can the discourse on state reforms truly represent the approximately 51% of Bangladesh's population who are women, particularly in state-building and equitable resource distribution?

Fauzia Moslem (FM): The core issue is society's flawed mental framework. The ideologies at play behind this are the main reason. Throughout history, women have actively participated in movements but remain unrecognised.

Olympe de Gouges, a key figure in the French Revolution, challenged the exclusion of women from the Declaration, which only referred to "citizens of France" without specifying women. Instead of recognition, she was executed. Ironically, working-class women ignited the revolution, yet their contributions were erased. The belief that women should not hold power persists even in the 21st century.

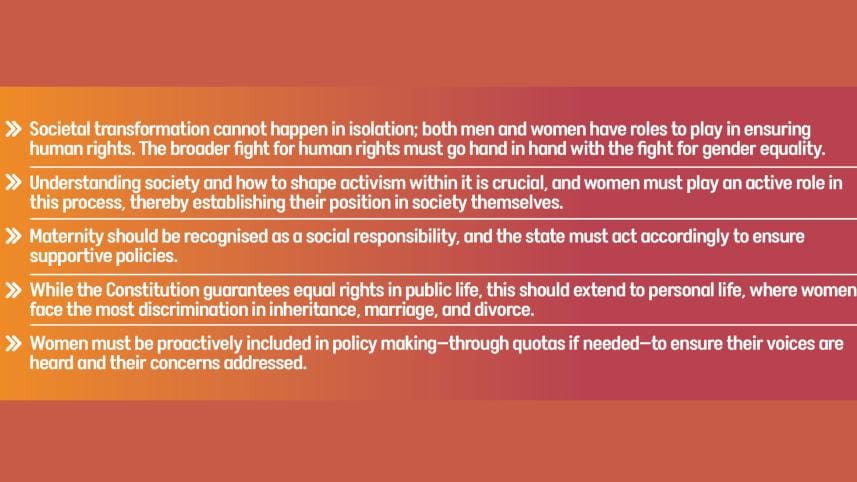

Women are actively mobilised during movements but are often sidelined once they conclude. Throughout history, movements such as those in 1952, 1969, 1971, and 1991 have propelled women forward, yet their struggle for recognition persists. Now, women must take the initiative to solidify their position in society, actively advocating for their rights and continuing to push for progress.

In this context, a sectoral approach focusing specifically on women is needed, as society as a whole often fails to accept them. This is precisely where the importance of the women's movement lies.

The reform committees lack female representation, prompting Mahila Parishad to submit recommendations. Our key proposals include direct voting for reserved women's seats in Parliament, equal property inheritance rights to reduce financial dependence, and legal protections against gender-based violence and child marriage.

Most reform commissions have to address these issues in some form. While the Constitution guarantees equal rights in public life, this should extend to personal life, where women face the most discrimination in inheritance, marriage, and divorce. Religious discourse often limits women's opportunities, reinforcing systemic inequalities. True reform demands women's inclusion in decision-making and policies that uphold their rights.

TDS: How do you assess the situation for women following August 5?

FM: Misogyny has become more visible in Bangladesh, particularly following the August 5 incident, which marked a significant increase in anti-women rhetoric. Misogynistic forces, along with a conservative societal mindset, have started to dominate certain spaces. If you observe social media, you'll notice a shift.

By discussing issues like clothing and religious sentiments, these forces are attempting to claim control of this space. They are trying, and while I would not say they have succeeded yet, their attempts are undeniable. We must remain vigilant about this growing communal and misogynistic group. It is not just the women's community, but society as a whole must stand up.

The problem is twofold: while women have made significant strides, society as a whole still has not evolved in its understanding of women's independence. Some individuals may have, but many still proudly say, "I allow my wife to work." Why should a husband have the authority to permit or forbid his wife from working? That decision should belong to the woman alone.

In the past, when we fought for women's rights, we were told, "Don't bring the movement into the household." But now, if you tell a woman not to bring the movement into her home, she will not sit quietly. If society had evolved collectively, women's progress would not face such resistance.

TDS: How effective is our legal framework in safeguarding and protecting women? Is it sufficient, or are there areas that need improvement?

FM: Legally, while existing laws are insufficient, they are not insignificant. If properly enforced, they could offer substantial protection for women's rights. However, the gap between legislation and implementation remains a major challenge.

For instance, the High Court directed all educational institutions to establish committees for addressing violence against women. However, this directive was never enacted into law.

Similarly, although the two-finger test for rape survivors has been legally banned and the Ministry of Health has issued protocols for proper medical examinations, the practice persists. This continues due to a lack of awareness among doctors and even lawyers and a misguided belief that the test is necessary.

Another example is the Family Protection Law, enacted in the early 1990s, which provides women with legal recourse within the family structure in cases of threats or violence. Yet, in all these years, only a handful of cases have been filed under this law—largely because people are unaware of it, and legal professionals seldom invoke it. The core issue is the severe limitations in accessing justice. The judicial system is in crisis, creating significant barriers, and women face these challenges even more acutely.

TDS: What do you think are the main obstacles that hinder women's representation, empowerment, and access to education, healthcare, and economic opportunities?

FM: The biggest obstacle is the lack of state accountability, which is not just a concern with the current government, but a systemic issue across all administrations. Despite international conventions, women's rights remain inadequately protected. This is not just due to religion but also communalism and state involvement in religious affairs.

The National Women Development Policy has never been fully implemented. Even under pro-Liberation governments, it was constrained by Islamic law. Another barrier is the institutionalisation of religious fundamentalism in governance.

Education must be gender-sensitive to drive societal change. Child marriage forces many girls to drop out, and the system must intervene to reintegrate them. Gender quotas are essential in education, employment, and leadership to combat systemic discrimination.

Media representation must also improve to reflect women's issues accurately. Without these reforms, meaningful progress in women's rights remains unattainable.

TDS: Despite the challenges, what positive changes have you observed?

FM: Overall, I see a positive shift in one important aspect—women now want to be empowered. In the past, many women stayed hidden, thinking, "Whatever little I get within my family is enough for me." Women are now eager to claim their space in society. This desire for empowerment is growing across all levels of society, from grassroots to elite.

Women's movements have become a collective force in some ways. More women are now engaged in various organisations. However, even though there is a growing focus on patriarchy as a central issue, we must remember that societal transformation cannot happen in isolation. Both men and women have roles to play in ensuring human rights. The broader fight for human rights must go hand in hand with the fight for gender equality.

I believe that the continuity of the movement, the relationship between the national movement and the women's movement, and how women should progress can be understood through past experiences and applied to today's actions. Ultimately, the goal remains the same: to dismantle patriarchy and establish equality. To achieve this, all women's movements must find common ground and unite, though there are still significant barriers to this unity.

TDS: Which key areas should we prioritise to ensure women's access to education, healthcare, and economic opportunities, while also promoting their participation in all sectors, including politics and society?

FM: First, we need to identify immediate steps that can effectively put an end to violence against women. Second, education must be prioritised. We need to ensure 100% primary school enrollment and increase women's participation in higher education, particularly in STEM fields. Third, employment opportunities must be expanded.

Advancing women's rights is essential to fulfilling international commitments like the SDGs. Women must be included in policy making, using quotas if necessary, to ensure their voices are heard.

Women's empowerment and the establishment of their rights are not tasks that can be completed overnight; they are ongoing processes that will persist as long as human civilisation exists. A significant gap remains between legal equality and lived reality. Women often face an impossible choice between career and personal life.

Historically, motherhood came with severe restrictions—women were confined, isolated, and subjected to rigid customs. Maternity should be recognised as a social responsibility, and the state must act accordingly to ensure supportive policies. While some of these traditions have faded, many patriarchal norms persist.

Transforming societal norms remains a major challenge for women's rights movements. Such deep-rooted patriarchal norms can only be reformed through cultural interventions, yet there remains a significant void in this area. Historically, literature, music, and cinema fueled social movements, yet such cultural expressions are now lacking. Reviving these mediums is essential for challenging outdated norms and achieving true social transformation.

The interview was taken by Saudia Afrin.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments