Aligning employer concerns with worker protections is key

The Daily Star (TDS): Why is labour sector reform the most urgent priority?

Syed Sultan Uddin Ahmed (SSUA): Bangladesh has undergone a major political transformation, driven by students, workers, and the public, all united in the pursuit of a non-discriminatory and equitable society. These issues did not emerge overnight. Bangladesh's history is deeply tied to workers' struggles, evident in the Liberation War, the 1954 elections, and the 21-point charter—all centered on equality and ending discrimination. Tea garden workers, sanitation workers, agricultural and industrial labourers have long faced exploitation and harsh conditions.

Workers have repeatedly fought against injustice, but systemic discrimination remains unresolved. Fragmented struggles—farmers' movements, workers' protests, and the fight for independence—have shaped our long-standing pursuit of equity. The events of 2024 result from continuous struggles and sacrifices. To realise our aspirations, we must address their root causes. Inequality is deeply entrenched, requiring not just reform but a transformation of the world of work. Time is slipping away—without action, we risk falling further behind.

TDS: Which areas has the commission identified for reform in both the formal and informal sectors?

SSUA: Exploitation of workers, systemic discrimination, lack of protection, and deprivation of basic rights remain critical issues. While modern industries have created jobs, they have also deepened inequalities—not just between employers and workers but within the workforce itself.

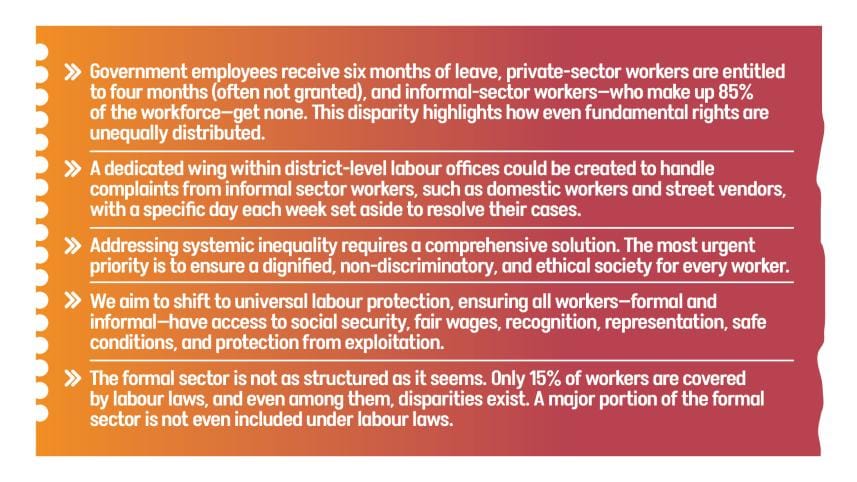

Take maternity leave, for example. Government employees receive six months of leave, private-sector workers are entitled to four months (often not granted), and informal-sector workers—who make up 85% of the workforce—get none. This disparity highlights how even fundamental rights are unequally distributed. Motherhood is a societal responsibility, because the child is part of the society. However, our system has created disparities even in such fundamental areas through law.

Inequality extends to employment structures as well. Permanent and outsourced workers often work side by side in government offices, yet the latter receive no job security, bonuses, or maternity benefits. Even the Prime Minister's Office employs outsourced workers under these conditions. Additionally, a recent government directive banning direct recruitment for fourth-grade positions blocks low-income families from securing government jobs.

Informal workers face even greater challenges. If a rickshaw puller can no longer work due to age or health, there is no pension or safety net.

Meanwhile, the formal sector is not as structured as it seems. Only 15% of workers are covered by labour laws, and even among them, disparities exist. A major portion of the formal sector is not even included under labour laws, such as journalists, junior officers in banks, factory supervisors, and mid-level managers. In the formal sector, a joining letter should be given, and a certificate should be provided stating the worker's employment history. Termination must follow a proper process. At the manufacturing level, there is no mechanism for grievance redressal.

Exploitation takes many forms, but fragmented grievances prevent a unified movement for change. If combined, the scale of injustice would be overwhelming. For example, four re-rolling mill workers died this year, and factory accidents continue unchecked. Minimum wages exist across 47 sectors, but disparities persist, revealing the formal sector's hidden informality.

Creating a non-discriminatory Bangladesh begins at home. When children witness the humiliation of domestic workers, they internalise and normalise exploitation. These ingrained biases later extend to the workplace, perpetuating systemic discrimination.

Our commission has been tasked with creating recommendations, but the problem is far deeper than anticipated. Addressing systemic inequality requires a comprehensive solution. The most urgent priority is to ensure a dignified, non-discriminatory, and ethical society for every worker. To achieve this, eight crore working people must be freed from these injustices.

We are recommending a three-way collaboration between academic institutions, industries, and skill development authorities. Industries should identify their workforce needs. Employers must forecast future skill requirements and communicate these needs to skill development authorities.

TDS: What are the core recommendations the commission has received from the stakeholders?

SSUA: Workers face numerous challenges, and we have received fundamental and logical recommendations through consultations with marginalised communities—tea garden workers, shipbreakers, garment and domestic workers, fishermen, health workers, and others. One major finding from our divisional meetings is that job security remains the core demand. Many workers face termination without rightful dues, and factory closures and government circulars, such as the retirement age of 60 for cleaning workers, have led to job losses without social security or pensions.

Stakeholders emphasised two key points: recognition for every worker and access to fundamental rights necessary for a decent livelihood. In addition to legal amendments, proper enforcement mechanisms should be in place.

Moreover, outsourced workers face corruption and bribery in recruitment as agencies alter hiring methods under various pretexts. Healthcare remains neglected, with a strong demand for specialised hospitals in industrial zones. Other urgent demands include ration cards based on occupation, due payments, emergency funds, simplified trade union processes, and legal reforms.

We also consulted employers, who raised concerns about bureaucratic hurdles, competition with large corporations, and business closures. They seek structured dispute resolution instead of abrupt shutdowns. Additionally, they highlighted the need for better worker mobility, particularly in sectors like hospitality and furniture-making. Addressing these issues requires urgent policy action.

Workers must have the right to organise. If we set a rule that a union can only be formed if 10% of an institution's workforce supports it—this may be suitable for a manufacturing unit, but not for occupation-based workers such as domestic workers, rickshaw pullers, or day labourers, so we advocate for a flexible system.

TDS: What challenges has the commission faced so far?

SSUA: One of the biggest challenges is managing expectations. Many workers and stakeholders expect the commission to directly address their demands. However, our role is to create recommendations, not implement policies.

Another major challenge is the vast number of stakeholders, each with unique struggles—from garment and health workers to shipbreaking labourers, sales representatives, and long-neglected Union Parishad Chowkidars and Gram Police. Many come from remote areas, seeking recognition. Despite time constraints, we have engaged extensively to ensure their voices are heard and included in our work.

There is very little data or research on many of these groups, making it difficult to develop precise recommendations. The available research is often too generic or secondary. Even the Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics (BBS) survey lacks sector-wise diversification, making it difficult to create targeted recommendations. For example, while the fisheries sector is documented, there is no specific data on subgroups such as dried fish sellers.

TDS: Could you explain how the commission plans to bring about structural reforms in the labour system?

SSUA: We aim to shift from employer-based labour protection to universal protection, ensuring all workers—formal and informal—have access to social security, fair wages, recognition, representation, safe work conditions, and protection from exploitation. A national minimum wage should serve as a baseline, with sector-specific structures built upon it.

Workers must have the right to organise. If we set a rule that a union can only be formed if 10% of an institution's workforce supports it—this may be suitable for a manufacturing unit, but not for occupation-based workers such as domestic workers, rickshaw pullers, or day labourers, so we advocate for a flexible system. A universal provident fund can ensure financial security for mobile workers.

We propose a permanent labour commission, overseen by a tripartite monitoring body, and a central labour database for transparency in welfare benefits. Aligning employer concerns with worker protections is key. Our goal is an inclusive, universally applicable labour law, ensuring all workers receive basic legal protections, regardless of their employment type.

Additionally, workers should have access to mechanisms for resolving grievances and securing settlements. Besides the court system, a dedicated wing within labour offices at the district level could be established to take complaints from informal sector workers, such as domestic workers and street vendors. A specific day each week could be set aside to resolve cases involving informal workers. This is not asking for much—it is a basic system to ensure that everyone has access to justice.

TDS: Regarding legal reforms, which areas is the commission focusing on the most?

SSUA: We aim to expand labour law coverage to include all workers, not just those in formal institutions. Key focus areas include occupational safety, health, workplace accidents, and compensation for all sectors. Strengthening the labour department will enable workers to file complaints, access social security, and engage in welfare funds. We propose a three-tier system for resolving disputes, ensuring that only critical cases reach higher courts. This would reduce the burden on labour courts and make the process more efficient.

For the informal sector, a dispute redressal system should be tailored to workers outside formal employment. For the formal sector, an Alternative Dispute Resolution (ADR) mechanism should be established. Serious disputes should be handled by labour courts as a last resort, reserved for cases involving criminal violations or major breaches of labour laws.

TDS: What recommendations has the commission made for women workers and child labourers?

SSUD: We aspire to create a child labour-free country but recognise gaps in community, union, and trade union involvement. Efforts have primarily depended on NGOs and government projects, often without sufficient accountability. The commission is assessing these shortcomings to tackle corruption and inefficiencies.

For child workers, employment must not hinder education. We propose linking employers with skill development programmes to ensure a "learning by doing" model.

Women workers need skill development to adapt to technological shifts and access alternative employment if needed. A major challenge is the lack of civic amenities in industrial zones. Many women leave their children in villages due to inadequate childcare facilities. Industrial zones must include schools, daycare centers, and hospitals. Women workers face systemic neglect, requiring a sector-wise approach to ensure their protection and well-being.

TDS: How is the commission working to improve skill development?

SSUA: Those who are ready are seizing skill development opportunities, while those who are not are being left behind. For example, if a factory introduces a new machine that replaces 10 workers, there should be a plan to train them to operate the technology rather than leaving them unemployed.

We are recommending a three-way collaboration between academic institutions, industries, and skill development authorities. Industries should identify their workforce needs. Employers must forecast future skill requirements and communicate these needs to skill development authorities. Skill development authorities should design relevant training programmes to equip workers with industry-specific skills.

Academic institutions should coordinate with skill development organisations to ensure graduates receive proper training before entering the job market. The goal is to ensure that students graduate with the necessary skills to enter the workforce immediately, without requiring additional training.

We aim to move beyond the mindset that any work is better than no work. Every citizen has the right to decent, meaningful employment, and it is crucial to ensure that no one is forced into indecent jobs or lives in uncertainty.

The interview was taken by Saudia Afrin.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments