We want NRBs to come back. But then what?

Reverse brain drain, a highly idealised concept, has been making waves on social media recently. The idea of returning from overseas as a highly skilled individual to contribute to the betterment of the country has always enticed the patriot in us all. Since the fall of the former autocratic regime and the subsequent renewed discourse on reforming the country, this concept has gained an even bigger spotlight.

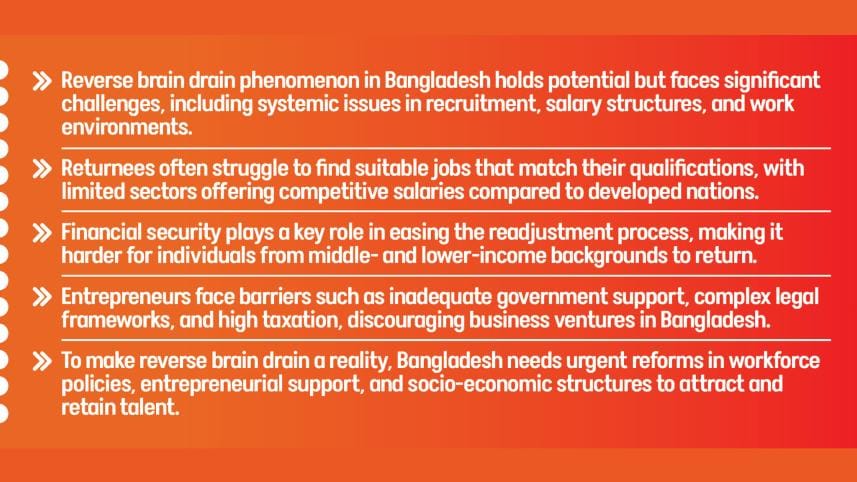

Indeed, having highly educated and skilled professionals return to the country can provide us access to an abundance of manpower. In these particularly trying times, successfully reversing brain drain would be a noteworthy achievement for Bangladesh. However, it is no small feat. It would require rigorously revising and reforming a number of policies and systems we have in place. In fact, the reality of returning is quite the mixed bag, and begs the question – is Bangladesh truly ready to accommodate these expatriates?

The factors influencing people to return to the country vary depending on individual priorities. While some people choose to return due to personal or familial ties, others may prioritise serving the country. Nerissa Nashin, an entrepreneur and certified makeup artist (MUA) returned to the country upon graduating from Swarthmore College, Pennsylvania out of similar patriotic sentiments.

"I always wanted to have an impact on my own people, and the market here was more appropriate for it. Whereas, if I stayed back in the US, I'd have an easier life, but it wouldn't be as meaningful for me," she said. She has returned to devote her career to combating colourism in the country's beauty industry. When asked about her reasoning she stated, "It had to do with a lot of experiences that I had growing up. But it was a combination of feeling passionate and thinking that this is the next logical step because the Bangladeshi market is ready for this, and nobody is really addressing it."

Meanwhile, Golam Morshed Jr Shan, a young barrister, returned from the UK upon completing his degree as he prioritised being with his family and building a career in Bangladesh. He said, "I knew if I had stayed longer there, I would have had a more routine and healthier lifestyle. But I preferred staying with my family and building a career in Bangladesh."

While their objectives may vary, many of the people who return come across similar obstacles, regardless of their field of work. Starting from securing suitable jobs to coping with unfamiliar salary structures and work environments, expatriates often have a hard time navigating and readjusting to Bangladesh both personally and professionally. For instance, despite their high qualifications, they often struggle when looking for jobs in Bangladesh.

"I've seen many friends of mine struggle to find suitable jobs for months. They have to settle for ones that don't fit their profile at all," said Laila Tasmia, a development professional who previously studied and worked in Europe. She went on to identify this issue as a result of systemic problems in the workforce, such as poor recruitment systems and prejudice among recruiters against specific countries of study as well as personal shortcomings of a candidate.

Even if they do manage to secure a job, few sectors are equipped to offer salaries on par with those of developed nations. While this issue is universally experienced, it adds a level of difficulty for people who are used to higher pay abroad.

"My friends in the UK and Canada get paid enough for personal expenses, rent, groceries, etc. On the other hand, many people I know in this field who are recent graduates and currently employed in Bangladesh earn an amount that can barely cover their personal expenses let alone larger ones such as rent and groceries," said Golam Morshed.

Although everyone navigates the same challenging readjustment process, affluence adds a degree of ease that people would not have otherwise. Having a financial safety net can allow people to take better risks in their careers and be more comfortable waiting for the most suitable career option. However, this is not the case for the vast majority in Bangladesh, including those who attain higher education or career experience abroad. Reflecting on her time working in Labour Migration, Laila Tasmia observed how class affects one's ability to readjust in the country. She said, "It is much easier to come back to the country if you are financially solvent. The upper class have a much easier time coming back and working due to their safety net, whereas the same cannot be said for middle- and lower-income households."

Business owners and entrepreneurs face similar challenges, which dissuade a number of people from returning to the country to start their businesses. Problems related to a lack of adequate government policies and funds and increased taxation – amongst other factors – have created an unsupportive environment that does not appeal to entrepreneurs who consider returning to the country.

Looking back on the initial stages of building her businesses in Bangladesh, Nerissa Nashin said, "I found that our systems are not equipped to support small businesses. It is very hard to navigate the legal frameworks, which are very flawed."

However, despite the challenges, people do choose to return. To some, remaining abroad poses greater challenges than returning. Laila Tasmia stated, "Staying back in Europe would have its own setbacks. In fact, both options have a unique set of problems. It's about which struggles you choose."

Nevertheless, it is evident that the process of rehabilitating these expatriates in Bangladesh has plenty of room for improvement. Persisting issues in the recruitment processes, salary structures, and work environments are more than enough for many of them to hesitate in their decision to return. Without adequate reforms, the number of people coming back to the country will decrease with time, depriving us of an abundance of human resources. Immediate action should be taken in order to encourage these individuals to return to the country and turn this idealised sensation of reverse brain drain into an attainable reality.

Waziha Aziz is a contributor for The Daily Star.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments