The role of higher education institutions in attracting global talent

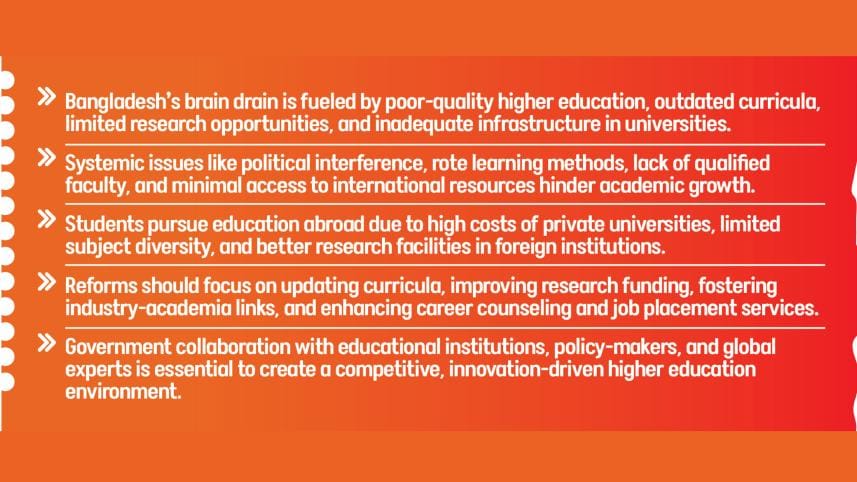

Bangladesh's struggle with brain drain is not new. According to data collected from 175 countries between 2007 and 2024, the 'Human Flight and Brain Drain Index' indicates that Bangladesh has the 37th highest propensity for brain drain. The reasons behind this high loss of human capital are multi-faceted and range from broad issues like political volatility and socioeconomic instability to infrastructural failings like unfriendly job markets and limited scope of career advancement. However, more often than not, talented young students are eager to leave the country, usually as early as after attaining their high school diploma, largely because of the deplorable conditions of higher educational institutions in Bangladesh.

While the number of universities in the country has steadily increased to over 150 in the past two decades, the same cannot be said about the quality of education. The University Grants Commission (UGC) is the body responsible for overseeing all tertiary educational institutions in Bangladesh. Even though the UGC is responsible for ensuring quality standards are being maintained across these institutions, its success is nearly abysmal. Dil Afroze Begum, an ex-member of the UGC, attests, "I tried for eight years to advise universities for their betterment, all to no avail."

On the systemic failings of the educational sector, Bahreen Khan, Assistant Professor at the Department of Law at Southeast University, says, "Students are frustrated with the entire system. They feel that due to internal politics, they are deprived of what they deserve from their university. Bangladeshi universities employ a backdated teaching system where teachers place excessive emphasis on memorisation. The teacher-to-student ratio in most classes is imbalanced. Teaching Assistants and Research Assistants are not available in many universities."

The summation of these problems means that the students do not end up receiving an education of a quality comparable to many foreign universities. The educational atmosphere lacks the practical training that is often necessary for skill translation into professional settings. The lacklustre facilities and resources are not helpful in the provision of quality education either. Muhammad Ihsan-Ul-Kabir, Lecturer at the Institute of Health Economics at the University of Dhaka, laments, "Quality education requires quality input like qualified teachers and multimedia classrooms. However, most of our university classrooms are not multimedia-supported. We don't even have access to international journals, which is a must so we can share the latest knowledge with students. These issues are massive detriments to tertiary education and a huge reason behind the ongoing brain drain epidemic."

The number of subjects offered by private universities is pitiable, with many not providing degrees in pure subjects like physics and chemistry. It is a massive constraint for students who might not want to pursue subjects that are traditionally offered. For passionate individuals who want to build a career in niche fields like automobile engineering, quantum physics, or molecular microbiology, there are no opportunities within the country. They are pushed to apply for undergraduate and graduate degrees abroad as that becomes their only path to pursuing their dreams.

The substandard research opportunities in the country contribute significantly to the poor performance of Bangladeshi universities in global rankings. "In addition to the problems surrounding the dearth of job opportunities in the public sector and the unreliability of job security in the private sector, the educational infrastructure in Bangladesh is also a driver for the problem of brain drain. It would not be an exaggeration to say that there is no research infrastructure in this country. The government fails to provide sufficient funding for laboratory development and private universities are not too keen to invest either. There is little scope to teach research or laboratory work to eager students," says Dil Afroze Begum who was also a Professor of Chemical Engineering at the Bangladesh University of Engineering and Technology (BUET) in the past.

Usually, there are two kinds of master's degrees offered—a research-based master's and a course-based master's. In Bangladesh, the educational environment is not conducive to doing a research-based master's. Through a course-based master's, there is an avenue for completing a thesis work. However, the research work done for the thesis is not extensive, and certainly not enough to prepare students for pursuing a PhD.

There is the added fact that PhD offerings in Bangladesh are few and far between. As of now, only 56 public universities in the country are allowed to offer PhD programmes. While the UGC said that they will allow private institutions to start offering PhDs, no progress has been made on that front. Moreover, given the country's poor research environment, the quality of the pre-existing research programmes is not ideal. Not to mention, there are no post-doctorate programmes in the country at all. Students who want to pursue PhDs, post-doctorates, and subsequent careers in academia are left with no choice but to turn to foreign countries to fulfil their educational aspirations.

Moreover, students may feel that there is a gap in terms of the quality of education they are receiving and the exorbitant fees they are paying for their degree. Due to the limited number of seats available as compared to the number of students vying for those seats, the competition for public university education is cutthroat, to put it lightly. One of the reasons why students want to attend public institutions rather than private ones is due to the high cost of a private university degree. According to the government's 2022 Household Income and Expenditure Survey, the average household income in Bangladesh is BDT 32,422 per month. Thus, paying 10 to 20 lakhs for a degree seems outlandish to many. Many talented students might feel that it is more worth it to find fully-funded degree opportunities abroad, rather than squandering the money on a local degree that is likely to be sub-par.

As the failings of the tertiary education environment are a major driving force behind brain drain, it is a logical progression to suggest that solving these issues can be massively beneficial to reversing the tide of brain drain. Amina Khatun, Assistant Professor of Mass Communication and Journalism at the University of Dhaka, opines, "By addressing the problematic areas, our public and private universities could enhance the academic landscape and enable graduates to remain in the country."

She continues, "Firstly, universities have to ensure quality education with updated curricula that align more closely with international standards. Educators have to begin emphasising critical thinking and problem-solving over rote memorisation."

A more practical approach to education will not only enrich educational experiences for students, it will also prepare them for employment. The dearth of job opportunities and unlikelihood of job security contribute significantly to brain drain. Thus, proper career counselling services within these universities that can provide students with comprehensive guidance about their post-graduation life will undoubtedly be helpful. Students can become more informed about the possible career options they have and envision a fulfilling professional life in Bangladesh, forgoing the decision to move abroad for better job prospects.

Additionally, by developing connections with local companies and employers, universities can aid students in two critical ways—providing them with internship opportunities to gain hands-on knowledge of the field they are interested in and creating pathways for them in terms of job placements and networking. It is also necessary to consult alumni, field experts, and employers when setting a curriculum to ensure that it can translate into desirable outcomes for graduates.

Hiring more educators, particularly educators who are highly knowledgeable about the field they are teaching is a necessity. Students don't require someone who simply tells them what is already written in the textbooks; they require mentorship and encouragement. A problem that many people have with Bangladeshi universities is the hostile or unfriendly attitude of many of the educators employed. That, coupled with problems caused by political interference, deters students from attending these institutions. Authority figures must take it upon themselves to ensure the quality of hire as well as proper behaviour from their faculty through equity committees, student council bodies, etc.

Bahreen Khan further says, "As the financial burden can be a barrier for many, an increase in scholarship access from private universities can mean that many talented students may take up local opportunities rather than pursue scholarships abroad."

Increasing research opportunities will be more difficult, but it is a task that must be tackled if we want to keep our strongest academic minds. There are no alternatives to investments in research. The government and individual institutions must take the initiative to develop research laboratories, acquire proper equipment, borrow foreign-born qualified educators, or send their own faculty members abroad for appropriate training so that proper research facilities can be provided and PhDs can be awarded on a greater scale. Amina Khatun says, "University authorities may take the initiative with several national and international organisations to collaborate in research programmes. This could help retain graduates passionate about pursuing academic careers locally."

As long as the research environment in the country does not improve, academics won't have an incentive to stay here. Besides, ensuring comparable pay, sufficient funding, an atmosphere conducive to cutting-edge research, and properly tenured positions can go a long way towards not only retaining students but also attracting highly skilled expat academics back into the country.

Investments in innovative, digital teaching methods, learning materials, and more diverse programmes of study are crucial, too, if we hope to stop talented individuals passionate about niche subjects from leaving. Tarnima Warda Andalib, Assistant Professor at BRAC Business School, opines, "Universities need to act like academic institutions and not like corporate organisations. Knowledge should be available everywhere with plenty of subjects and up-to-date syllabi and facilities."

However, the burden is not on these educational institutions alone. Bangladesh's tertiary education sector needs a complete makeover if it ever wants to stop the brain drain. That scale of remodelling has to start from a policy level. The government has to collaborate with policy-makers, intellectuals, academics, industry experts, and students to redesign higher educational institutions in Bangladesh so that they can stop the flight of human capital.

Adrita Zaima Islam is an intern for Campus, Rising Stars, and Star Youth, The Daily Star.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments