The missionaries and the evolution of the Bengali language

In his foreword to Bernard Cohn's magisterial book Colonialism and its forms of knowledge, Nicholas Dirks commented that for the British, in India, "Language was to be mastered to issue commands and to collect information." Bengal was the province where the British imperial project started to take shape after 1757, and the Fort William College was set up by Lord Wellesley in 1800, to train young British administrators in the languages of command. The Fort William College was fundamentally important in the evolution of the Bengali language, which led to the Bengal Renaissance of the nineteenth century, and contributed to the extraordinary political and literary revolution that defines Bengali culture to this day.

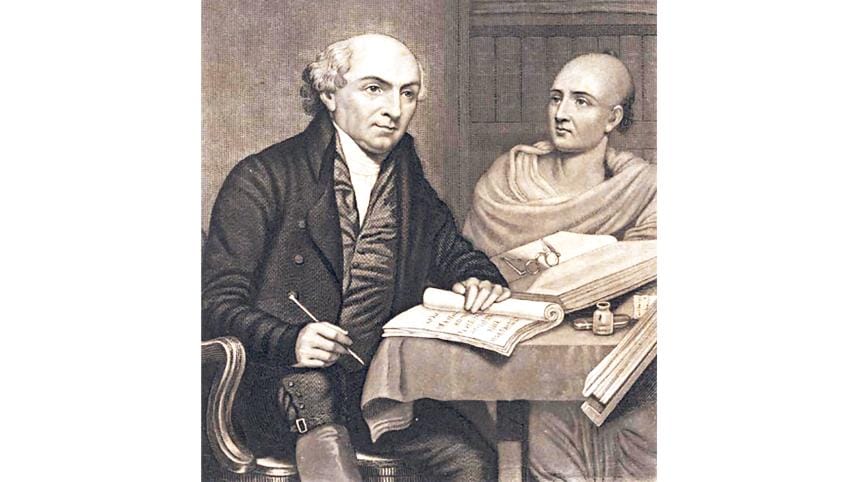

There is an important ideal that Wellesley had in mind when he set up the College, that has now been forgotten – "To maintain and uphold the Christian religion in this quarter of the globe." All professors and lecturers had to swear an oath that they would not teach anything contrary to the Christian faith. It is not surprising then, that the Sahibs at the College were either devout Christians or missionaries or both. The most famous example of such a Sahib would be the Baptist missionary of Serampore, William Carey, known to posterity as "The Father of Modern Missions." Carey was appointed the head of the Bengali language department at Fort William College in 1801. He soon found that though Bengali was the language of Calcutta and its hinterlands, it was a neglected language in the curriculum. Sisir Kumar Das in his book Sahibs and Munshis, documents the relentless battle Carey had to fight to keep Bengali language education on an equal footing with Hindustani and Farsi at the Fort William College between 1801 and 1830. When questioned about the efficacy of learning Bengali, Carey answered, "Were it properly cultivated, it would be deserving a place among those which are accounted the most elegant and expressive." Carey, as the head of the Bengali language department at Fort William College, needed Indian teachers. He also needed to solve the problem of a lack of primers that the young civilians at the College could use to learn Bengali.

Missionaries, from Carey and the Serampore Baptists onwards, understood the importance of cultivating Bengali, the language of the milieu they inhabited. For the Serampore Baptists, this led to a huge project of learning Indian languages, beginning with Sanskrit and Bengali. They began the work of writing new grammars to facilitate translations and cultivated close ties with Indian intellectuals. To disseminate this knowledge widely, Carey's associate, the printer William Ward, set up a printing press at Serampore. The most important technician at this press was Panchanan Karmakar, who had assisted the British typographer Charles Wilkins in creating the first wooden Bengali typeface in 1778, to print the first Bengali grammar by Nathaniel Brassey Halhed. Karmakar had been lured away to Serampore by Carey and Ward, and he created another Bengali typeface for Carey's Bengali translation of the New Testament in 1801.

This is where an interesting collaboration emerges between the Serampore Baptist Mission and the Fort William College. If we consult Brajendranath Bandopadhyay's list of pundits and munshis employed as Bengali language instructors at Fort William College, it becomes very clear that all of them were hired as a result of Carey's recommendations, and they cultivated close connections with the Serampore Baptist Mission in return. Carey, in his roles both as an educator and as a missionary, needed competent linguists and translators who could help in the collection, translation and interpretation of classical Sanskrit and Bengali texts, which could be then printed and disseminated widely. His wide circle of acquaintances and associates at Fort William's Bengali department solved his problems.

In this early flowering of the Bengali language in the print medium, we find the names of pioneering authors of Bengali texts like Mrityunjaya Bidyalankar, Ramram Basu, Goloknath Sharma, Tarinicharan Mitra, Chandicharan Munshi, Rajiblochan Mukhopadhyay, Ramkishore Tarkachuramani, Mohanprasad Thakur, Haraprasad Roy, and Kashinath Tarkapanchanan, employed at Fort William College under Carey's supervision and a part of his patronage network. Among these authors, Mrityunjaya Bidyalankar's translation from the Sanskrit of the Thirty-two Thrones (Battrish Singhasan) and his Beneficial Advices (Hitopadesha), Ramram Basu's Garland of Alphabets (Lipi Mala) and The History of Pratapaditya (Pratapaditya Charitra), Chandicharan Munshi's Bengali translation of the Farsi The Parrot's Tale (Tooti Nama), and Rajiblochan Mukhopadhyay's The History of Maharaja Krishnachandra Ray of Nadia (Maharaj Krishnachandra Rayasya Charitram) are important documents.

These are not only best examples of early Bengali prose but also represent developments in Indian modes of translation-theory and an Indian historiography. Brajendranath called Mrityunjaya Bidyalankar the first "conscious artist" of the Bengali language. These literary works, used widely as pedagogical aids in Bengal at least until the 1870s, were all initially published at the Serampore Mission Press. In thirty years, only briefly interrupted by the great fire of 1812, the Serampore Mission Press printed over two hundred thousand books in more than forty Indian languages, including Bengali. Among these were the first printed versions of Krittibas's Ramayana in five volumes and Kashiram Das's Mahabharata in four volumes in 1802. Sajanikanta Das commented that all future Bengali versions of either the Ramayana or Mahabharata were modelled on the Serampore editions.

The missionaries inaugurated the great age of print revolution in India and helped to create a Bengali public sphere where British policies were debated by Indians. This first period of the vernacular public sphere began with Rammohan Roy's debates with the Serampore Baptists between 1815-1820 and continued up to the ban on Sati in 1829. Many of the important teachers and officials at the Fort William College figured prominently in public sphere debates between 1810 and 1830. For example, Mrityunjaya Bidyalankar, who left Fort William College in 1816 to become the head pundit at the Calcutta Supreme Court, was a leading critic of the Sati ritual. It was his written opinion in 1817, to the Chief Justice of the Sadar Dewani Adalat at Calcutta, that can be considered the first protest against this inhuman ritual by an Indian intellectual. His opinion is also the unacknowledged inspiration for the much more widely remembered pamphlets against Sati written by Rammohan Roy, published in 1818 and 1820.

Michael Madhusudan Dutta, Christian convert and one of the greatest innovators of poetic form, rhythm and meter in the Bengali language, began his linguistic experiments after a long and frustrating period of writing in English. His inventions include the epic Meghnad Badh Kabya, a retelling of the Krittibasi Ramayana in the mode of Milton's Paradise Lost; the Bengali sonnet or Chaturdashpadi; as well as the Amitrakshar Chhanda, based on the iambic pentameter in blank verse. In his sonnet Banga Bhasha (The Bengali Language), he eulogized the splendid riches of one's Matri-bhasha, mother tongue. Bengali, to Madhusudan, contained all the Bibidha Ratan characteristic of a highly developed language. It was a bejewelled net that could capture all human emotions and experiences and express their many varied registers in a multitude of literary forms. The evolution of Bengali from its older crude prose form of the late eighteenth and early nineteenth century, to the highly sophisticated modern version that Madhusudan praised and that we are familiar with, happened within a span of barely half a century. It was a process that undeniably started at Fort William College. We therefore should not forget the role of visionaries like William Carey, who saw the potential of Bengali language, and fostered the network of Indian linguists and teachers who first shaped the modern Bengali language into its written forms, before it was refined further by Indian polymaths like Ishwarchandra Bidyasagar, Bankimchandra, Rabindranath, Mir Mosharraf Hossein and Abdul Karim Sahitya Bisharad.

Our pride and our hope, Ò†gv‡`i Mie, †gv‡`i AvkvÓ, our Bangla Bhasha, owes a great debt to Bengal's forgotten Christian missionaries.

Mou Banerjee is an Assistant Professor of History at the University of Wisconsin-Madison.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments