Are we doing enough for our SMEs?

One significant dimension that has emerged in Bangladesh in recent decades is the expansion of small and medium enterprises (SMEs). The growth of SMEs, especially in the last one decade, has been quite astonishing. From the mid-1980s, the number of SMEs has increased four to five times. The contribution of small, micro and medium (MSME) enterprises to the country's GDP has also reached as high as 25 percent, while their number increased to 7.9 million. In addition to its direct contribution, SMEs play an important role in the supply chain of many other goods and services. It is not only in terms of contribution to national output/income, but primarily of the capacity of SMEs in generating employment that has helped shape the rural economy in particular. As many as 24 million people are estimated to be engaged in SMEs, which is around 30 percent of the total employed workforce. Moreover, SMEs are gradually becoming one of the key sources of employment generation for women.

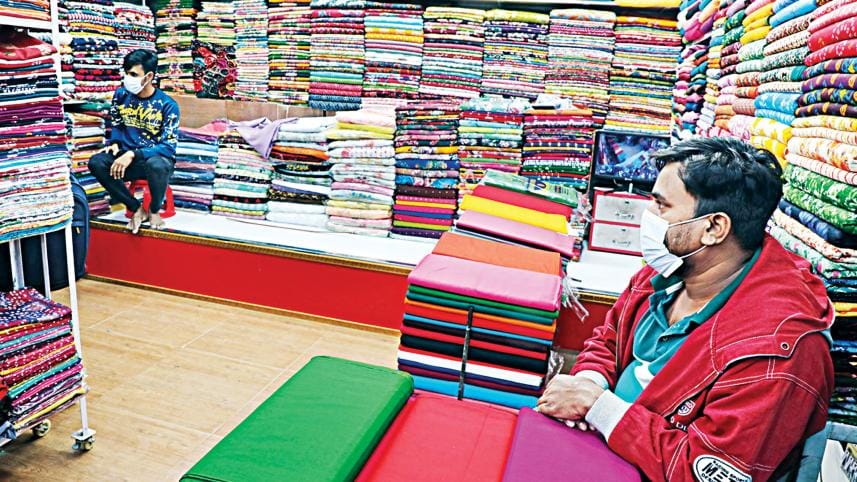

During the Covid period (i.e., 2020, 2021), SMEs, especially the micro and small enterprises, despite being hit hard by the pandemic, served as a source of livelihood for a large number of people. The sector, however, has several structural bottlenecks that are constraining its potential expansion – which includes constraints related to access to marketing, access to finance, access to information, infrastructural bottlenecks, technological shortcomings, etc. Additionally, there are certain fundamental issues related to the SMEs, which include the disagreement in terms of its definition and classification along with the informal nature of many of the enterprises. Therefore, in order to reap maximum benefits from this sector, we need targeted policy interventions.

The most crucial bottleneck for the growth of SMEs is probably related to their difficulty in accessing credit for their operation and expansion. Formal financial institutions are often reluctant to extend loans to SMEs due to their pre-conceived belief that it is unsafe to fund SMEs, especially the small and micro-ones, as these enterprises might be unsustainable in nature. Besides, many of the small and micro entities might find difficulty in accessing formal credit due to their informality or lack of required documentation. Many SMEs, therefore, tend to obtain loans from informal channels or from NGOs at high interest rates, resulting in high cost of operations for them. In order to circumvent this constraint, though the government as well as the central bank has taken different initiatives for encouraging and incentivising the commercial banks, there has not been much improvement in terms of access to credit from formal institutions.

SMEs have increasingly expanded to the online arena, where the main regulatory body is the e-Commerce Association of Bangladesh. This type of business model is being preferred particularly by female entrepreneurs as it involves less mobility for business operations. However, restraints related to internet services, digital literacy, fragmented nature of the business, limited market base, etc. are some of the drawbacks for this type of businesses.

With a view to facilitate the expansion of SMEs, the government has taken a number of initiatives, including the formation of the SME Policy of 2019. It emphasises supporting SMEs in three key areas – supportive policies, effective institutions, and access to services related to business and finance. In addition, the five-year plans, the perspective plans, along with the industrial policy of the government have also emphasised strategies in relation to the development of the SME sector.

From an institutional point of view, for SME development, the Ministry of Industries serve as the apex regulatory body with a number of other organisations including the SME Foundation. In addition, a wide range of government, non-government as well as (semi) private entities are also engaged in the development of SMEs, which includes Bangladesh Small and Cottage Industries Corporation, Micro Industries Development Assistance and Service (MIDAS), NGOs like Brac, PKSF, etc. All of these institutions are involved in the development of SMEs through a wide range of initiatives, but there still exists a number of fundamental problems in regards to the operation and expansion of the activities of SMEs. Such constraints are related partially due to the small and fragmented structure and informal nature of the SMEs.

Like many other countries, SMEs in Bangladesh have also suffered badly during the initial years of Covid and many even had to close down their operations. In this regard, the government announced a recovery package for SMEs, which primarily constituted subsidised loan facility. Empirical evidence (e.g., firm level primary survey conducted by Sanem – a leading think tank in Bangladesh) suggests that it was the micro and small enterprises that suffered the most during the pandemic, followed by the medium ones, with the pace of recovery being much slower for these enterprises. In terms of the utilisation of government stimulus packages, the micro and small firms in particular were left behind with very small percentages of them having been able to avail the low-cost loan facility. According to a survey on 500 firms conducted by Sanem, only 9 percent of micro and small firms and 30 percent of medium firms were reportedly able to avail it, while the percentage was found to be as high as 46 percent for the large enterprises.

One of the more important areas of intervention for the government is to facilitate the activities of women entrepreneurs. In this connection, the Bangladesh Bank in its SME Credit Policy of 2010 requires commercial banks to lend to women entrepreneurs, and has also introduced a targeted women's credit policy. The SME Foundation has also been working to bring women entrepreneurs into the mainstream development process through a number of initiatives like institutional capacity building of women chambers and trade bodies, formulation of gender action plans, encouraging bankers to finance women entrepreneurs, etc. Despite the initiatives, women owned SMEs in particular suffer three broad challenges: i) constraints in accessing credit from formal enterprises due to their lack of network, low mobility, lack of collateral, absence of gender sensitive supportive environment, etc; ii) lack of information about available finance, business opportunities, marketing, etc; iii) lack of linkages to the supply chain of products and lack of marketing facilities. Though these challenges exist for both male and female entrepreneurs, they are found to be more acute for women.

Given the enormous potential of SMEs, and in particular due to its contribution in small scale employment generation, much greater policy emphasis is needed towards them. As outlined in the new SME policy, the government can facilitate the operation and expansion of this sector by formulating favourable policies and strategies, by strengthening the institutions related to the SMEs and, of course, by fulfilling their financing requirements. The most important thing to consider in this context is to have a favourable regulatory environment in terms of finance, business operation, etc. – and for this it is important to have more flexible financing requirements (e.g., less documentation), separate treatment for the micro and small enterprises due to their vulnerable status, greater flexibility in terms of regulatory requirements (e.g., requirements in terms of trade license), etc. It is also extremely important that the government as well as the central bank incentivises the private banks to extend credit to the smaller entities.

Besides, in order to enable SMEs to benefit from different available facilities, there must be effective mechanisms to integrate the informal entities into the regulatory structure. As for the female entrepreneurs, the government can play a crucial role by providing supportive facilities to link them to the market by setting up and expanding support services in each of the upazila offices, by offering greater degree of flexibility in terms of documentation, legal requirements, collateral, and above all, by practicing gender-sensitive service delivery at the supply side.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments