Women professionals in Bangladesh

The long, arduous road from Raj to Partition to Liberation left our new-born country with an economy too small to accommodate many of its able-bodied men, let alone its women. Patriarchal values entrenched in our social mores meant that this was explained away using morality and the idea of the 'good' woman as being a caregiver above all is something that took decades to change.

For women in my dadi's generation, 'acceptable' career options were limited social work and education, nursing and midwifery, and domestic service, depending on the socio-economic background. The monetary value of household work was not considered in GDP calculations; and neither was the contribution women in rural communities put in towards agricultural/artisanal activities. It was simply taken for granted that taking care of the home was something women were supposed to do, and in fact, to have a career up till the late '70s was an exception to the norm.

When the Middle East began accepting migrant workers, and the birth of the RMG sector happened, the cash injection into the economy relaxed these restrictions and we saw an influx of women in factory jobs, and at executive to middle-management levels in the emerging corporate sector. The key word for this stage was 'pressure:' we had to prove ourselves capable of holding down a job — if we were allowed to get one — we had to make sure we didn't neglect household duties, and we had to do this without any necessary infrastructural or policy-level support. The fact that women managed to rise to the highest offices in the country proved our mettle for self-determination.

As the economy continued to grow, there was better investment, with microfinance schemes and NGO led support for women in the SME sector. Education being made mandatory for women definitely had a positive effect in improving our occupational mobility.

By the time millennials like myself entered the job market, globalisation had provided us with the advantage of greater exposure, and we were better equipped to fight for our needs – for pay parity, for policy level protections such as maternity leave, sexual harassment policies, and for a seat at the table in general. Women were now branching out into areas previously closed off to them; particularly in STEM fields.

The road ahead

Fifty years of the evolution of women in professional spheres in Bangladesh has seen many milestones. We have a bright, capable workforce, and opportunities our forebears could not have dreamed of. Yet, there is so much work to be done. Even with greater awareness, 2020 has shown us that safety remains a key concern, and a barrier to mobility. Our educational system needs a complete overhaul if we are to face the challenges, global and national, that lie ahead.

When I look back on my career of twenty years, I feel humbled by gratitude at the sacrifices made by women of my grandmother's and my mother's generations to pave the way for us, and for the amazing female role models I had when I started out, who instilled in me a strong work ethic and motivated me to be the change I wanted to see. If it isn't too presumptuous of me to offer advice to young women entering their careers now, it is that they have every right to dream big; but they have to be prepared to work hard to achieve those dreams.

Life never goes the way you plan, but if you keep a positive attitude and give it your 100 percent, what amazing things you will achieve!

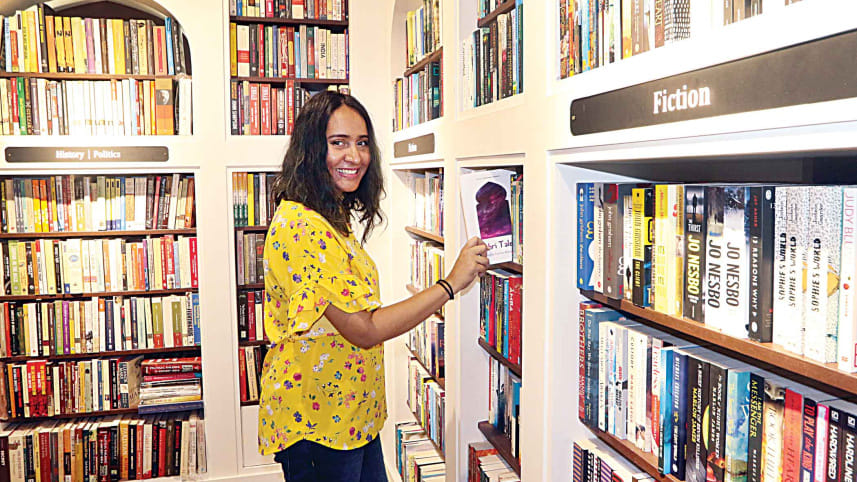

Sabrina Fatma Ahmad is a journalist, academic and author. Having begun her career at The Daily Star, she is currently Features Editor at Dhaka Tribune. She is also the founder of the Sehri Tales writing therapy project, and the author of Sehri Tales, an anthology of poetry and micro fiction.

Photo: Prabir Das

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments