The future of housing in Bangladesh

In the 1920s, the French-Swiss architect and pioneer of modern housing, Le Corbusier, declared: “Architecture or revolution.” Corbusier was warning that if society fails to produce and provide adequate housing to its members, there will be social unrest and agitation. That is one reason why the core activity of early modern architecture was dedicated so much to housing.

Housing is a complex social and economic dynamic whose results are the physical patterns of cities and settlements, the qualities of collective living, and the health and well-being of the people. Housing is thus a social and material fabric of any city and settlement; it is the key to enhancing the quality of life of the immediate dwellers and the overall city. Yet, housing suffers from many misconceptions and poor practices in Bangladesh.

In the rapidly growing economy of Bangladesh, housing should be a significant factor in both maintaining and supporting the economy. While sectors like infrastructure, industry and connectivity enjoy prioritised attention, we feel that housing as a foundational sector of development deserves a much bigger, thoughtful and creative focus.

In spite of the fact that there is a national housing policy in place and a vibrant real estate market in the country, we feel that there is an urgency for a renewed attention to housing, and transforming policies into actions for qualitative as well as quantitative changes. Consequently, Bengal Institute for Architecture, Landscapes and Settlements maintains “settlements” as one of the focus areas of its studies and propositions.

FROM HOUSE TO HOUSING

The most important element of housing is its collective nature. There is a major difference between house (“bari”) and housing (“boshoti”); the former refers to a single entity involving a household, and the latter begins with an ensemble of houses or units. The ensemble or collective is not simply a matter of quantity; it suggests a social and shared realm that is part and parcel of a larger human habitation.

"Everyone has the right to a standard of living,” the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR) announces, that is “adequate for the health and well-being of himself and of his family, including food, clothing, housing and medical care and necessary social services, and the right to security in the event of unemployment, sickness, disability, widowhood, old age or other lack of livelihood in circumstances beyond his control."

Historically, housing has come into greater political and social focus since the Second World War in Europe, with the urgent need for reconstruction and rehabilitation of peoples, and in newly decolonised countries for improvement of living standards of its citizens across the economic spectrum. In this case, the vision and actions of Jawaharlal Nehru, the first prime minister of India, to provide housing and create exemplary models remain an important benchmark. In today's globalised world, housing becomes critical beyond the socio-cultural and economic factors as it intersects with environmental changes. In a developing country as ours, housing is also a geographic challenge, in which housing and architecture can affect vulnerable and precious ecologies in fundamental ways.

HOUSING FOR ALL

The constitution of the People's Republic of Bangladesh entrusts the government in ensuring access to shelter for all citizens. Article 15 of the constitution states that the government has a responsibility to provide access to basic necessities, including shelter. While the government does not have the obligation to immediately provide shelter to all, it implies that a citizen of any strata of the society has the right to have access to shelter. However, since independence, government action has addressed this issue in a negligible manner. In this regard, government employees and a privileged section of the society are the only ones who have benefited from government action. A vast majority of the population have to depend on their own self-initiatives in accessing this basic necessity.

To make matters worse, the metropolitan hub Dhaka has no suitable large-scale models for housing that cater to the different economic groups that inhabit the city. The public sector housing, catering to government and corporation employees, still continues along the defunct line of erecting one building after another with no thought for in-between spaces. The middle-class is living by making do what it can in the brutal housing and rental market. The limited and lower income groups have been completely ignored in the housing equation. And when they mobilise on their own to create an active community against an unsupportive environment with their limited resources but infinite inventiveness and fortitude, they face eviction and alienation.

It is evident that in a country where rich are getting richer and poor are getting poorer, there is a lack of affordable housing, especially for the people of low-income groups. According to the census on slum dwellers and floating population conducted by the Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics (BBS) in 2014, 2.23 million people live in slums across the country. The increased population indicates the increased demand on housing. A report suggests, seven out of ten households in Bangladesh dwell in conditions that are not permanent (Saleh, 2017). Clearly, more housing is required for more diverse needs.

HOUSING FORMS SETTLEMENTS

Typically, the term “housing” often conjures up an image of repetitive building blocks of residential units in an urban setting. It is however much more than that. Housing exists at different scales and in different hierarchy of settlements—from rural landscapes to small towns, and from medium towns to large metropolitan areas. Housing can be a collection of houses within a para or neighbourhood in a village; a collection of houses within a moholla or neighbourhood within a town, be it small, medium or large; and blocks or neighbourhood in a metropolis. From the design point of view, each and every situation requires careful consideration and research, as densities and amenities vary for each scale.

As housing is fundamentally a large-scale operation, it has a particular relationship with the larger context, be it an open landscape or a metropolitan environment. In most cases, housing is presented as an urban phenomenon; it is in fact the foundation of urbanism.

The issue of the house in rural areas cannot be easily equated with the house in the city. In rural areas, people mostly build houses on their own using local resources and building technology. But there is certainly a change in the use of materials and use of spaces even in villages. The national housing policy suggests that the government will take necessary steps for appropriate rural housing to secure food security and environmental conservation. But people are prioritising concrete built forms now over traditional houses. As a result of this, traditional building types, which are more sensitive to the environment, are decreasing in number. High-rise buildings in small towns which are built with zero considerations to city planning are ripping apart the older urban fabric, both physically and socially. While this uncontrolled phenomenon continues, the experts are neither taking necessary steps to preserve the local architecture nor creating alternative housing opportunities.

Even in bigger cities, platoons of housing experts are still floundering with two dead-end models: the individual plot with the independent bungalow-style house, and the individual plot with a clunky apartment building. The two do not add up to a wholesome whole, neither do they create any fabric of a residential complex that is a cohesive community with an admirable quality of life. The dull strategy of making “new” housing areas by plotting and subdividing land—plotting and scheming—should be stopped immediately, and alternative imaginative models of mass housing should be explored. Let us not demean the nature of the free-standing house, but it should be erected where appropriate. Do we want these houses in the heart of the city? And if so, then within which urban fabric or system?

Large-scale examples in Dhaka, such as Bhashantek Rehabilitation Project and Japan Garden City, and others, are intrusions on the cultural landscape as well. They contribute little to a historic continuity of our social living experiences or the pattern of buildings and spaces that make viable urbanism.

THE ECONOMIC FACTOR

With housing becoming primarily a profit-making enterprise, the true economic benefits of proper housing are also misunderstood. There is a misconception that housing has less contribution to economic growth compared to other sectors of investment as returns can be long-term resulting in less allocation of resources as well as attention in comparison to other sectors. However, the economic contribution of proper housing is manifold and the most important one is the impact on the health and productivity of the people.

We are observing a succession of construction works of industrial establishments all over the country but we do not see any matching effort in construction of housing for the workers of these establishments. Rather, it is left to the speculative behaviours of the land owners of the adjacent areas whose priority would be in maximising returns. The workers remain at the mercy of these landlords and the benefits of any increases in the workers' wages are mostly appropriated by them. The thrust of establishing economic zones is probably only on land development for industrial construction, and not including housing along with it. The concerned authorities must consider that improved living conditions will increase the productivity of workers by directly reducing their illnesses and health risks. Proper housing environment not only increases productivity but also reduces health care costs and this can increase the purchasing power of the workers.

Besides health, a vibrant housing sector attracts private savings in mobilising funds for investments in this sector. Increase in proper dwelling units will also increase the municipal tax base compared to substandard ones which are often out of any enumeration. In comparison to haphazard and unplanned housing, properly designed and planned ones increase efficiency in land use, especially in a country like Bangladesh, where efficient use of land is of prime importance. Increased activity in the housing sector will contribute to the development of a dynamic construction industry, entrepreneurship, expansion of building materials manufacturing, furniture-making, transportation service, employment generation and most importantly development of infrastructure. Housing, therefore, is also an economic priority.

QUALITY HOUSING SHOULD BE A PRIORITY

It is the combination of economic and cultural strengths that makes housing a factor in sustaining societies. Hence it is very important to improve and maintain certain standards while planning housing. However, discussion on housing usually gets bogged down to numbers, that is, quantity not quality. Chasing numbers can only result in an environment that may fall short of a decent, liveable one.

Our rush to economic development has already given rise to many environmental issues requiring remediation. Qualitative aspects have been greatly neglected and the accelerated thrust in housing should not be devoid of this. Qualitative aspects of housing need to be clearly established and incorporated in rules and regulations so that they are not left out in the design, planning and delivery process. Of many aspects of quality we emphasise the following five as key ones: health and hygiene, durability, mix of communities, sustainability, and affordability.

The quality of a healthy environment through housing has major implications for people's life whether it is in rural or urban areas. Sunlight, natural ventilation, good water quality, proper sewage and waste disposal, available greenery and community spaces, all have health benefits and should be made a mandatory part of the design. Maximising the number of units should not be the only priority; rather maximising while ensuring a healthy environment should be the priority.

It is said that if the life of a building can be doubled, the environmental impact can be halved, making environmental and economic benefits of durability a key factor for quality housing. A durable building is one that lasts a long time, provided it takes a longer period of time to amortise the environmental and economic costs that were incurred in building it. In the construction of buildings, durable, environment-friendly and low maintenance products and materials must be considered. Durable products, materials and construction techniques with a service life of over 60 years without the need to be replaced or repaired as frequently should be used. Therefore good solutions for houses depend on the use of materials and methods that are well designed to meet the demands of society and the requirements of the new era. The result would be a building that could last longer and that would be more economical and energy efficient, creating more sustainable solutions for future generations.

Quality housing should be socially and environmentally appropriate. The type of accommodation, support services and amenities provided should be appropriate to the needs of the people to be accommodated. The mix of dwelling type, size and tenure should support sound social, environmental and economic sustainability policy objectives for the area and promote the development of appropriately integrated play and recreation spaces. It is perceived that the communities are stronger with more homogeneous groups of people, but retaining a social mix can be a key priority and the main reason for preserving affordable housing in high-cost areas. Mix in income group for quality housing should be encouraged since this helps people aspire to better things. Mixed communities, and in particular communities of mixed income and housing tenure size, are intended and alleged by their advocates to have a range of beneficial effects upon neighbourhoods and their residents.

Sustainability—“meeting the needs of today without compromising the needs of future generations”—is another aspect of quality to be considered for housing. Sustainable housing must aim at economic, social and environmental sustainability from planning to implementation phase and at the same time result in housing that is affordable, accessible and environmentally less damaging. Components like solar panels, wind turbines, verandas and rooftop gardening, cross ventilation using larger openings and any other elements that can help to have positive impacts on home temperatures by reducing the demand for heating and cooling system must be used. As a result, it will reduce emission, save cost and improve the ambience, aesthetic and air quality. Promoting sustainability as a major element of quality housing will help to ensure liveability and proper functioning of the ecosystem of a city.

For those living and working in the city, the constrained housing supply and increasing unaffordability of housing are both having significant sustainability impacts. It also puts pressure on welfare spending on housing benefit. Factors related to demographic and socio-economic backgrounds such as household income influence housing adequacy and affordability. Because of the inherent difficulties affecting housing costs and employees' capacity-to-pay, the need to secure or improve housing affordability is an enduring issue that housing project planners have to address. Hence, to have quality housing, affordability needs to be taken into consideration. If affordability in housing is to be properly and adequately addressed, there is a need for policy initiatives and interventions to assist the median income earners as well as incorporation of social housing as a priority development policy.

Models of affordable housing, while ample in the world, are in short supply in Bangladesh. One rare example is a case from Jhenaidah, where it successfully shows the benefits of promoting people-centred planning, which is one of the significant ways to ensure affordable housing. In 2014, Co. Creation.Architects and Platform for Community Action and Architecture (POCAA), under Khondaker Hasibul Kabir, and a local NGO named Alive, initiated the process of Jhenaidah Citywide Community Upgrading with some help from Asian Coalition for Housing Rights (ACHR). This process allows underprivileged people to participate in building community housing through their savings. Through community mapping and profiling activities, problems and opportunities within the community are identified by the people themselves. Throughout the process, the people in the community also receive financial, technical, legal, planning, merit support and skill development assistance (Co.Creation.Architects Publication, 2018).

CHALLENGES FOR BANGLADESH

Affordability alone does not solve the crisis of adequate housing; the quality of the environment must be prioritised as well. The impressive economic growth of Bangladesh as well as some

social indicators of development have been receiving considerable attention from different quarters of the world. Let us note that environmental degradation of human habitats and natural landscapes has also not gone unnoticed. Housing being an

important and essential component of living deserves emphasis beyond the

simple objective of attaining numbers. The emphasis has to shift to quality. While there are staggering numbers to be attained, we need to give greater attention to the quality of environment that encourages healthy, energetic and a fulfilling life.

In the context of India and Bangladesh, there is a critical turn in housing. While housing was a state affair under the socialist model in the 1950s and 60s, in which attention was given to various economic classes, now housing has been usurped by the forces of market economy.

Housing is no longer a question of dwelling but more a commercial capitalist enterprise in a neoliberal economy. Less seen as a building of social communities, the term “housing” is seen as land allocation and apportionment in a climate of real estate extremism, in which there is more subsidy for those who have, and none for those who have less. Housing is now understood more through banking language as loans, mortgage, equity, etc. Production of housing has changed from the independent “tower” as a model, but there is still not much provision for the high-density low-rise. The housing footprint and its ecological impact are calibrated from the accountant's desk, overruling the factors of ecology.

With a housing shortage of six million, the overall housing situation of the country is poor compared to the pace of development. BBS claims there was a housing shortfall of 4.6 million units for 43.43 million people in 2010. The shortage is projected to reach 8.5 million units for 60 million urban people by 2021. If the total urban population reaches 100 million by 2050, a minimum of 0.1 million housing units should be supplied in the market every year.

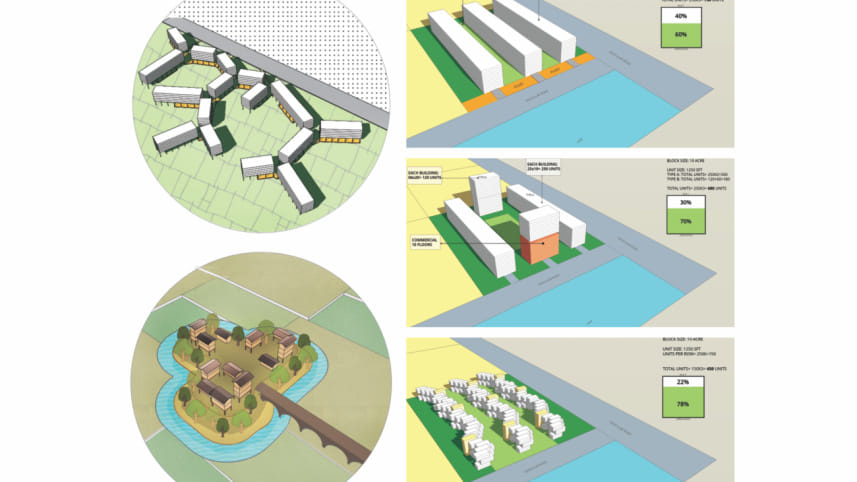

The bigger challenge is to provide housing or housing opportunities for the vast multitude of people living in vulnerable conditions. Creative economic partnerships and incentives may go towards creating housing of diversity. Government land may be given to developers for dense development with the purpose of creating a community where a certain percentage in the area/volume in the development should be built for low-income/middle-income habitation. Needed are enlightened developers and engaged state to create both new models and opportunities.

WE NEED A VISION FOR HOUSING

We are basically suffering from a lack of vision of how we are going to live collectively. It is critical to explore new alternative and imaginative models of mass and group housing for every economic and social group with a process to deliver them. The intention should be to achieve greater density, better quality of life, and shared lifestyle. The current situation requires a clear-cut path to attaining the housing objectives as identified. We have identified the following three key initiatives.

Improving existing stock

Fulfilling the demands of the backlog as well as of new needs will surely require development of new housing but there is also the scope of upgrading the existing stock. This can be done by renewing and retrofitting the existing stock. Mindless demolition of the existing and replacing it with newer and taller buildings is not the answer for all of the existing housing. Each existing housing is linked with other amenities like schools, clinics, markets, playgrounds and increased density creates pressure on them and the services cannot cope with the demand.

Moreover, some of these existing areas provide a unique identity to the city and their replacement with the so-called modern ones alters the particular characteristics of the location that might have developed over the years. A policy of “careful urban renewal” is thus required. Each and every case should be evaluated prior to any demolition and construction of the new.

For example, it appears that the architectural and engineering authorities of the state are working at full speed in taking down the old walk-up buildings in Azimpur Housing Estate in order to replace them with tall towers. As one of the earliest designed housing projects in Dhaka, Azimpur has been etched in the memory of the city, as well as in generations of government officials and their families who lived a precious part of their lives there. Considering the historical value of Azimpur as an urban fabric, and that it is a prime site of about 50 acres in a premier part of the city, we are looking forward to an exemplary solution to the challenge of renewal and renovation of a well-known neighbourhood of the city.

New housing

The demand for future housing and the backlog can only be fulfilled by new housing, and that too in the shortest possible time. Several generations since independence have passed their childhood and later periods of life in substandard living conditions. The process of adding new housing should be made as clear as possible with targets clearly identified.

First and foremost is the need to identify suitable locations including land requirement for future housing and it should be brought under development control. An example to follow would be the process the government has adopted for establishing the economic zones all over the country. In fact the development of the economic zones needs to be synchronised with housing development for the population to be employed in these zones. Establishing density requirements in relation to the scale of the development and location aspect with respect to the settlement hierarchy and amenity requirements are corresponding requirements with land and location identification. Density requirements also need to adhere to the objectives of quality housing.

To meet the dire need of housing we must encourage group housing which allows high density. Group housing also suggests the experience of a community. This is critical in the context of Dhaka today as the older structure of communities, such as the moholla, is fast disappearing, and the current pattern of buildings hardly encourages community experience. Dhaka has become a city of fragments, with its social cohesiveness tattering away, broken down to the individual households living in their walled fortresses or sealed-off apartments. The general form of a city—its physical and spatial configuration—is capable of nurturing or disrupting the nature of communities.

Most urban planners and policy-makers focus on the core city for housing models. Even when they are dealing with the edge, they see it in the image of the core. Official planning is unable to conceptualise this edge, to recognise that the edge is its own ecology and a critical one. Without that realisation it is easy to participate in the destruction of the city's hydro-geographical landscape. The edge is where new forms of housing and other space organisation in response to a fluxed landscape will have to be reorganised, along with newer types of opportunities for social sustainability. Imaginative housing strategies can be seen as a way of managing the urban edge, whether in a metropolitan or small town context.

Many architects have shown us compelling examples with their housing projects. In the Indian context, Charles Correa and BV Doshi have designed projects like Belapur Housing and Aranya Housing consecutively which are a great example of low-rise community housing for low-income people. In response to the geographic question, projects like Silodam in Amsterdam (by MVRDV) and Xixi Wetland estate in China (by David Chipperfield) are built in respect to the water bodies while providing density and quality housing.

Ensuring smooth and quality delivery

The government formulated the National Housing Policy in 1993, which was revised in 1999 and again in 2016. How much of this policy is being transferred into reality? How much have we achieved so far?

There should be coordination between DCC, RAJUK, concerned ministries and utility agencies in urban projects, while administrative procedures should be decentralised to ensure transparency in the implementation of housing projects. Private sector should be given responsibility to construct housing units for medium- or high-income households while low-income housing projects could be done by a specific entity, as RAJUK has failed to focus on the housing for the poor (Shams, 2014).

Housing, whether provided by the public, private or public-private partnership, needs to be a well-coordinated activity. This will require strengthening as well as making effective the existing institutions and creating new institutions. National Housing Authority has an immense role to play and the authority should be well represented by different stakeholders. Owners of future housing should be made part of the process. As already mentioned, design and planning play an important role in creating quality housing and efforts should be taken to involve the best minds to offer their services. Similarly, finance, construction, ownership and maintenance, all need to be clearly spelled out.

Kazi Khaleed Ashraf, Saif Ul Haque, Masudul Islam Shammo, Rubaiya Nasrin, Farhat Afzal, Hassan M Rakib, and Maria Kipti of Bengal Institute for Architecture, Landscapes and Settlements contributed to this article.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments