Jobs abroad for a better life

International migration for employment is an important channel through which the process of economic globalisation works. Although this channel is relatively less active compared to the other channels like international trade and cross-border flows of capital, it is growing in importance because of differences in the rate of growth of population and labour force in different parts of the world. While there are some countries like Bangladesh, where labour force is growing at a rate higher than the rate of employment growth, there are those where the opposite is the case. This creates situations for workers to move from the former type of countries to the latter. There is a long history of emigration of the people of Bangladesh in search of jobs and better life, but short-term migration for jobs is a relatively recent phenomenon. The flow of such migration has become increasingly substantial over time—with, of course, a good degree of fluctuation from year to year.

Overseas employment not only helps workers and their families in improving their lives, it makes a valuable contribution to the economy of the country. This can be gauged from several pieces of statistic. First, the annual flow of remittances has increased from less than 2 billion USD in 2000 to over 15 billion USD in 2014-15 when remittances received were equivalent to about 8 per cent of the country's GDP. For Bangladesh, this is the second largest source of foreign exchange earnings after ready-made garment exports. In fact, it has contributed substantially to the recent building up of foreign exchange reserve of the country. Remittances in 2014-15 were equivalent to about 61 per cent of the reserve in 2014-15. Second, in terms of employment, during the three-year period of 2012 to 2014, about half a million people found jobs abroad every year—representing over a fifth of the annual addition to the total labour force of the country and over half the additional jobs created by the manufacturing sector in recent years. It is thus clear that overseas employment is important not only from the macroeconomic point of view but also in terms of employment.

While overseas employment and workers' remittances are playing a very important role in the economy of Bangladesh, an important question is the cost—monetary as well as non-monetary - at which this is happening. The monetary costs incurred by the workers and their families in the process of going abroad with jobs (or sometimes without a specific job but only with a “promise” of a job) is very high, and the non-monetary costs take a variety of forms ranging from the adverse effects on family life and on the development of children of families split by long absences of one of the parents. The main focus of the present article is on the costs involved in the quest for improved life; but we start by looking first at who migrates, why they migrate, and what process one has to go through.

Around five lakh people have been finding jobs abroad in recent years

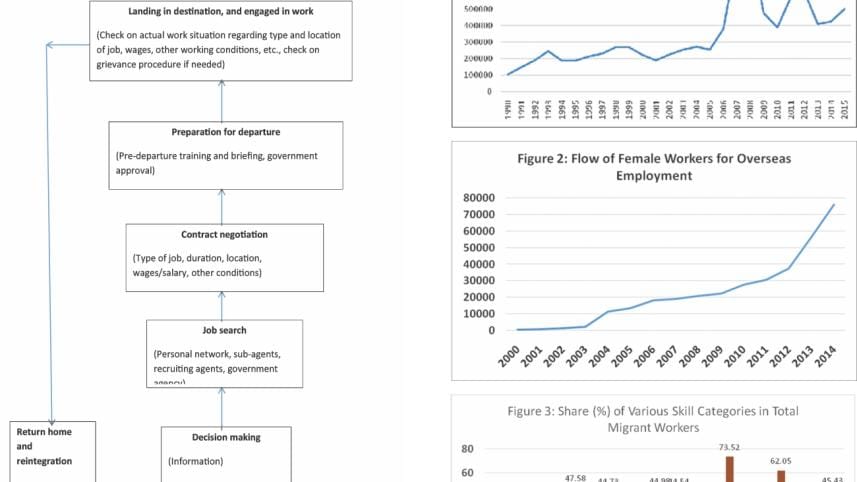

While emigration of people from Bangladesh has a long history, short-term migration for employment started in the 1970s and picked up pace gradually. From just over 6,000 in 1976, the number of people going abroad for jobs increased to around 100,000 by the end of 1980s. But the pace gained momentum during the 2000s and after 2005, there was a sharp increase in the flow for a couple of years (Figure 1). However, that sharp rise was short-lived and the numbers in recent years have hovered between 400,000 and 500,000.

Although workers from Bangladesh find employment in a large number of countries of the world, a few countries in the Middle East (e.g., Saudi Arabia, Kuwait, United Arab Emirates, Bahrain, Oman and Qatar) and in Asia (viz., Malaysia and Singapore) account for most of the jobs. Of course, there has been a change in the mix of major destination countries for workers from Bangladesh, and some developments are worth noting in that regard.

- In recent years, especially after 2007, there has been a sharp decline in the flow of workers to Kuwait, Saudi Arabia and Malaysia.

- The decline mentioned above has been made up to some extent by a rise in the flow to Oman, Qatar, Lebanon and Singapore.

- On the whole, there has been a slight diversification in the destination countries for overseas employment of workers from Bangladesh. Up to 2005, the major eight countries (viz., Saudi Arabia, UAE, Kuwait, Qatar, Bahrain, Oman, Malaysia and Singapore) accounted for over 95 per cent of the flow, but declined gradually after that to about 74% in 2014.

The trend of overseas employment by gender indicates that in the past women accounted for a negligible proportion of migrant workers from Bangladesh. However, there has been notable increase in the number of female workers going abroad in recent years (Figure 2).

Most of the migrant workers are young with low levels of education and skills

Most of the migrant workers from Bangladesh are young men with low levels of education. Although the number of women going abroad with jobs has increased in recent years, as proportion of the total, it remains small. Most migrant workers are below 40 years of age (for women, more than half are below 30). A majority of them (i.e., all migrant workers) have low levels of education (below SSC), and another fifth completed SSC or HSC. Graduates account for just over five per cent of the total.

The majority of migrant workers of Bangladesh are in the unskilled (“less skilled”, in the terminology used by the government) category, although in recent years, there has been some increase in the proportion of semi-skilled and skilled workers (Figure 3). While migration of skilled workers can have potential benefits in terms of higher paid jobs and hence higher remittances per worker, there are negative implications as well, especially in terms of the costs of training and loss involved in brain drain.

Is poverty the major factor driving migration?

Historically, in many societies, poverty has led people to migrate from one country to another in search of means to avoid starvation. But Bangladesh has now come a long way from the acute poverty that characterised the country in the 1970s? Why, then, people are still so keen to go abroad for jobs? Empirical analysis shows that the probability of migrant workers belonging to upper income groups is lower than in the case of the lower income groups. This may lead one to conclude that it is basically the poor who go abroad for jobs, and it is poverty that is the major driver. But given the high cost involved in the process of migration for jobs abroad, whether the poorest can afford that is an important question (more on this below). The reality of course is more complex, and one major driver of migration appears to be the lack of employment opportunities within the country and an aspiration for higher incomes and better living. As mentioned above, most of the migrant workers have low levels of education (SSC-HSC or less), and they are the ones who suffer from the highest rate of unemployment in the country. So, it is unsurprising that they are so keen, and often desperate, to go abroad for employment.

Jobs abroad: the cost is very high

The process of migration for work is beset with abuses and exploitation that include high costs and fees, attachment to a stipulated employer (which goes against the principle of freedom to choose employment), divergence between contractual obligations and real conditions at work (especially payment of wages that are lower than stipulated in the contracts), and so on. Particularly vulnerable are workers with low education and no skills and women workers. For the latter, especially for those who work as domestic help, in addition to abuses suffered by migrant workers in general, an additional risk is sexual harassment. An ILO report (ILO, 2010) sums up the situation in these words:

“While international migration can be a positive experience for migrant workers, many suffer poor working and living conditions, including low wages, unsafe working environments, a virtual absence of social protection, denial of freedom of association and workers' rights, discrimination and xenophobia. Migrant integration policies in many destination countries leave much to be desired. Despite a demonstrated demand for workers, numerous immigration barriers persist in destination countries. As a result, an increasing proportion of migrants are now migrating through irregular channels, which has understandably been a cause of concern for the international community. As large numbers of workers – particularly young people – migrate to more developed countries where legal avenues for immigration are limited, many fall prey to criminal syndicates of smugglers and traffickers in human beings, leading to gross violations of human rights. Despite international standards to protect migrants, their rights as workers are too often undermined, especially if their status is irregular”. (ILO, 2010, p.2).

The situation for migrant workers from Bangladesh is no different from the general picture depicted above. Despite a number of step taken up by the Government of Bangladesh to protect the rights and welfare of migrant workers (see below), there are challenges that remain.

While abuses suffered by migrant workers are regularly reported in media, it is difficult to get concrete data, except on costs involved in migration and fees charged by agents. On other aspects, apart from media reports and anecdotal evidence, there is not much by way of concrete data. For example, some data are available on the number of complaints received from migrant workers, but the breakdown of such complaints by their nature is not available. Moreover, the pace of getting any redress also is rather slow. One study (Wickramasekara, 2014) reports that in Bangladesh, out of a total of 3116 complaints received during 2009-2013, only about 55 per cent were settled.

How does the cost compare with those in other countries of South Asia?

High costs incurred by migrant workers is a major issue in many countries, but Bangladesh is at the top in this respect. In 2008, the actual cost per migrant going to the Middle East was between USD 2991 and USD 3263 (about Tk. 250,000 at the current exchange rate) compared to the next highest figures of USD 1181 to USD 1737 in India. The cost was the lowest in Sri Lanka where it was less than USD 800. Similar figures are reported for migrant workers going to Malaysia and Singapore. In relation to GDP per capita, the cost in Bangladesh was 4.5 times while in the Philippines and Sri Lanka the figures were only 0.5 and 0.25 respectively (i.e., half and one fourth of GDP per capita). Such sharp differences in the cost of migration to similar destination countries imply differences in the effectiveness of administration of migration.

Nearly 60 per cent of the cost in Bangladesh is accounted for by the so-called intermediaries (read: dalal), 18 percent by “helpers”, and another 10% represents “agency fee”. Although under different nomenclatures, the above figures show that 88% of the cost is accounted for by “facilitators” of the process of migration. It is thus clear that a prospective migrant worker from Bangladesh has to pay large sums to recruiting agents and other intermediaries at various stages – and the payments per worker are the highest in the region.

Mobilising something like Tk. 250,000 is not easy for a low-income family; and that is often done by taking loans from relatives and friends or by selling the meagre amount of land (and other assets) the family might possess. But given the salary that one earns abroad, the savings that can be generated and remitted back home, and the consumption needs of the family left behind, it often takes years to recoup the lost assets and start rebuilding.

Instruments exist to protect the rights of migrant workers, but they are often ignored

There are international conventions/standards that are aimed at protecting the rights of migrant workers. Examples are various ILO and UN Conventions on migrant workers and the ILO's Multilateral Framework on Labour Migration. Unfortunately, however, many of the destination countries have not ratified any such instrument. It is thus difficult to obtain an assessment of the situation regarding the rights of migrant workers from such countries. In fact, absence of ratification itself is an indicator of the poor situation in this respect. The following observations may nevertheless be made about the situation.

- In many instances, a prospective migrant worker does not receive formal contracts (especially in a language that is understandable to him/her) before their departure although this is a basic element in the guidelines (Guideline 13.3) of the ILO's Multilateral Framework on Labour Migration (MFLM) adopted in 2006. Moreover, it is quite common to substitute the contract offered prior to departure with one that is inferior in terms of wages and other conditions of work.

- Several international instruments (e.g., ILO's MFLM and Conventions C181 and C189) specify that no fee should be levied on workers; and yet, charging of fees from prospective workers is a common practice (not just in Bangladesh but in other sending countries as well).

- Both Conventions 181 and 189 provide for negotiation of bilateral agreements to prevent abuses and fraudulent practices in recruitment and placement. But such issues are often left out of bilateral agreements.

- Guideline 13.2 of the ILO's MFLM stipulates that recruitment and placement of workers respect their fundamental rights; and yet, given the system of tying of workers to a specified employer, confiscation of passport upon arrival in destination countries, and the requirement of exit permit, many workers find themselves in situations of forced labour.

The Government of Bangladesh has undertaken a number of initiatives to address the challenges in the administration of migration for employment abroad; they include:

- District Employment and Manpower Offices (DEMOs) have been strengthened in order to provide migration related information to prospective migrant workers and their families;

- BMET arranges to provide pre-departure orientation to migrant workers before they travel abroad;

- The government, in collaboration with NGOs and other stakeholders, is making efforts to raise mass awareness on safe migration procedures through dissemination of relevant information;

- BMET has a Wage Earners' Welfare Board that is mandated to provide various services to migrant workers that include pre-departure briefing, scholarship for workers' children, repatriation cost of deceased migrant worker, and grant for deceased workers' families;

- Bangladesh has bilateral agreements with Kuwait and Qatar and MOUs with Hong Kong, Iraq, Jordan, Republic of Korea, Libya, Malaysia, Maldives, Oman, and UAE.

- Probashi Kalyan Bank (Expatriate Welfare Bank) has been set up with the objective of providing credit for meeting the costs of migration, helping smooth transfer of remittances at low cost, and encourage investment in productive sectors;

- In 2011, the government ratified the International Convention on the protection of the rights of all migrant workers and their families;

- The Overseas Employment and Migrant Welfare Act, 2013 was passed by the parliament of Bangladesh in 2013. The Act has provisions for providing protection to migrant workers against possible abuses. Rules are being formulated for the implementation of the Act.

What can be done to improve the situation?

Despite various steps taken by the government to protect migrant workers from exploitation and to promote their welfare, the situation remains far from satisfactory. A good deal more can and needs to be done in this regard. Some suggestions are being provided here, with a view to strengthening the institutional framework for a more efficient, transparent and effective governance of the migration process.

- Issues relating to the rights and welfare of migrant workers encompass a number of stages in the cycle of the process of migration, work abroad and return (Chart 1). The starting off point is the process of decision making for employment overseas during which a prospective worker needs information on a variety of aspects including the costs involved, jobs that may be available for him/her (taking into account her age, qualification, etc.), additional training that may be required, expected wage/salary, location and conditions in which the work is to be done, and so on. In order to enable an informed decision, it is important to make available as much information as possible.

- Once a decision is made, the next stage is to get into the act of looking for a job, and that is when the recruiting agents and their sub-agents start playing a role, although a significant number may be getting a job through personal networks. Once the search for jobs is completed and negotiations have been undertaken with the sub/agents and a licensed recruiting agent, the worker should look for a clearly specified contract in her hand.

- Irrespective of the mechanism used for getting a job, the prospective worker would need to follow the existing procedure (including registration with BMET and government's approval) that is prescribed under government regulations.

- Upon arrival at the destination country and the location of duty, the important steps include registration with the nearest Bangladesh mission, checking whether the actual terms and conditions of the work match with those specified in the contract, and checking out on the grievance procedure, if needed.

- Measures are needed to protect the rights and promote the welfare of migrant workers at each of these stages. Depending on the stage of intervention and nature of action, they could be in the nature of facilitation, promotion, regulation or protection. At the stage of decision making, the prospective migrant would benefit from information of different kinds (mentioned above) which could be provided through various channels ranging from conventional electronic and print media, social media, and awareness raising campaign by both government and non-government organisations that are present at the grassroots level. Apart from information about prospects of jobs in different countries and qualifications required for jobs of different kinds, it would be particularly important to provide information about the excessive charges made by the recruiting agents and sub-agents, and the dangers of migration through irregular channels.

- The mechanism for the search of jobs overseas can be made more efficient and transparent by requiring recruitment agencies to post information about jobs available on their websites. Likewise, for recruitments made by the government (for example within the framework of the G2G mechanism), information may be posted on the website of BMET. It is at the stage of job search that migrant workers face the highest probability being misled and exploited by agents and sub-agents, and hence, measures will be needed to protect them from such dangers. While laws and regulations as well as punishment for offenders are essential, they alone will not be sufficient, especially in a situation where desire and incentive to migrate are very strong. It would be important to provide the prospective migrants with choices and alternatives to the “services” provided (or promised) by agents and sub-agents. Strengthening and extending the reach of the public sector recruitment agency as well as innovative measures to help job-seekers link up with employers or their legitimate agents can play a useful role in this regard. If properly mandated and strengthened, District Employment and Manpower Offices (DEMOs) could potentially provide an alternative to “services” provided by sub-agents.

- For negotiating contracts, the government could play an important role by setting the basic standards in terms of wages for different categories of workers and different destination countries, other conditions of work, e.g., weekly time off, health care and care in case of emergencies, insurance against accidents, etc. Such model contracts could be used by the government in arriving at bilateral agreements and MOUs with different countries. Although such agreements do not provide complete solution to all the issues involved in labour migration, they can be a useful instrument for protecting the rights of workers to a large extent.

- Where bilateral agreements or MOUs don't exist, the government could still provide basic guidelines for negotiation of contracts with prospective employers in different countries which could be used by recruitment agencies and could provide a point for reference for prospective migrants.

- In the destination countries, missions of Bangladesh, through the Labour Wings, could play an important role in minimising (if not completely eliminating) abuses of workers and violations of rights they face. Of course, in order to achieve desired results, those offices would have to be strengthened both in terms of quantity and quality, i.e., by increasing the number and improving the capability of the responsible officials.

- It must be clear from the above discussion that the act of international migration for employment overseas is difficult, and likewise the task of managing the process can be quite complex. The complexity of the task of governance and management can be gauged from the simple fact that the relevant players are located all over the country of origin and the countries of destination, and hence are subject to the situation and rules and regulations of different countries. A large number of players are involved in the process. At the highest level, the Ministry of Expatriates' Welfare and Overseas Employment has the responsibility to oversee the whole process, and especially for handling political instruments like bilateral agreements and MOUs. The Bureau of Manpower, Employment and Training (BMET) is responsible for managing/regulating the process of overseas employment. The Wage Earners' Welfare Board is mandated to provide various services to migrant workers that include pre-departure briefing, scholarship for workers' children, and grant for deceased workers' families. As for regulations, the Overseas Employment and Migrants Act (OEMA) 2013 and the Overseas Employment Policy draft of 2014 provide with measures and actions that are needed to regulate the whole process and protect the rights of migrant workers. And yet, serious challenges remain, especially with regard to rights and welfare.

To conclude, rights of workers and rights at work are important concerns for all workers and is an area of special concern for migrant workers because they face risks of violations and abuse on both sides—the sending as well as the receiving country. The issue of rights is closely linked to governance of the process of migration which suffers from a number of problems. Improvements are urgently needed in the governance of migration in order to ensure an orderly and abuse-free process of migration.

The author, an economist, is former Special Adviser, Employment Sector, International Labour Office, Geneva

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments